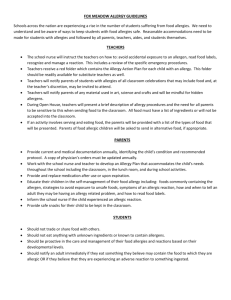

Food Allergies in South Africa WAO Dec 2011(Claudia Gray).

advertisement

Food Allergy in South Africa: Joining the Food Allergy Epidemic? Dr Claudia Gray MBChB, MRCPCH, MSc, DipAllergy, DipPaedNutrition Red Cross Children’s Hospital Allergy and Asthma Clinic, Cape Town, South Africa 1. Background There is increasing evidence of a current rise in the prevalence of food allergy, dubbed the “second wave” of the allergy epidemic, enigmatically lagging behind the initial rise in respiratory allergies by several decades. This rise in food allergies has been described mostly in westernised countries. Here, rather phenomenal statistics such as a 2-fold rise in peanut allergy in the last 10-15 years1 and an incidence of challenge-proven food allergy in up to 10% of young children 2 have been published recently. In Africa, there is evidence of a significant increase in respiratory allergies, 3 mirroring the pattern of that in westernised countries though seemingly lagging behind a little. However, there is a real dearth of studies looking at food allergies in Africa, and in the handful that have been performed, data reflects sensitisation and sometimes questionnaire-base allergies which notoriously overestimate true allergy. Anecdotally, despite often significant sensitisation rates, the prevalence of clinically significant food allergy in South African children-especially those of Black indigenous decent- has been reported as extremely low.4,5 Particularly peanut allergy, which has received much attention of late in the western world for its sensational recent increase, was virtually unheard of amongst Black South Africans until a very short time ago. This experience led to a belief that Black South African children may be protected from the food allergy epidemic. Possible protective factors include rural diet, high microbial load and unique gut microflora in the context of genetic and epigenetic influences.6,7 However, South Africa is an ethnically diverse nation, and differences between ethnic groups in allergy expression are a real possibility but poorly studied to date. Moreover, the indigenous Black population, traditionally with a low rate of reported food allergies, is rapidly urbanising and taking on new diet and lifestyle. Based on the hypothesis that food allergies are still uncommon in South African children, especially those of Black decent, we recently studied a population at “high risk” of food allergy, namely children with atopic dermatitis. We hypothesised that, even in this high risk group, food allergies would be less common than in our westernised counterparts. To our knowledge this is the first study in South Africa looking at food-challenge proven food allergies. The study is summarised below 8: 2. Study summary: The prevalence of IgE mediated food allergy in South African children with Atopic Dermatitis 2.1 Objectives: The primary objective of our study was to determine the prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy to common allergenic foods in South African children (6 months-10 years) with atopic dermatitis, attending the dermatology clinic in a tertiary medical centre in Cape Town, South Africa. Foods tested were cow’s milk, hen’s egg, peanut, cashew nut, soya, wheat and white fish. 2.2 Design: A prospective observational study run between March 2010 and September 2011. 2.3 Recruitment: Randomly selected, consented children with atopic dermatitis attending specialist dermatology clinic at Red Cross Children’s Hospital 2.4 Diagnostic modalities used for diagnosis of food allergy: Food allergy questionnaire Skin prick testing (SPT) Food- specific IgE (using immuno solid phase allergen chip- ISAC Phadia™). If diagnosis equivocal- open oral food challenges. (n=68) Rigorous definitions for food allergy using history and tests 2.5 Ethics: Study approved by the University of Cape Town research ethics committee 2.6 Definitions: Sensitisation: positive SPT ( 3 mm) and/or specific IgE (>0.3 ISAC units) Allergy: sensitisation to a food AND convincing history of a reaction to the food in the preceding year OR positive food challenge. 2.7 Results: 100 children completed the study (mean age 45 months), 41 of mixed race (mean age 50 months) and 59 Xhosas (mean age 42 months) All patients had moderate or severe AD: moderate(SCORAD 15-40) n= 48; severe (SCORAD > 40) n= 52 Sensitisation: overall 66% of patients showed sensitisation to at least one food, most commonly egg (54% of patients), peanut (42%) and cow’s milk (26%). Allergy: 42% of patients had at least one food allergy, most commonly peanut (26% of patients), and egg (24%). Out 56 cases of food allergies in 42 children, 34 were diagnosed by food challenge and 22 diagnosed by sensitisation AND convincing recent allergic symptoms. 2.8 Ethnic Differences: The ratio of allergic patients: sensitised patients was significantly lower in Xhosa patients compared with patients of mixed race (21/41 versus 21/25, p=0.007). SUMMARY TABLE1: OVERALL SENSITISATION AND ALLERGY Any sensitivities % (n) Any allergies % (n) Mixed Race (n=41) 61% (25) 51% (21) Xhosa (n=59) 69% (41) 36% (21) Total (n=100) 66% (66) 42% (42) SUMMARY TABLE 2: BREAKDOWN FOR INDIVIDUAL FOODS Mixed race (n=41) Xhosa (n=59) Total (n=100) 24% (10) Peanut sensitised % (n) 49% (20) Peanut allergic % (n) 39% (16) Cow’s milk sensitised % (n) 34% (14) Cow’s milk allergic % (n) 4.8% (2) 59% (35) 25% (15) 37% (22) 17% (10) 20% (12) 0% (0) 54% (54) 24% (24) 42% (42) 26% (26) 26% (26) 2% (2) Egg sensitised % (n) 46% (19) Egg allergic % (n) 2.9 Discussion of study results: The prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy in this at-risk population of South African children with atopic dermatitis is high This population-previously protected from the food allergy epidemic- now shares equivalent rates of sensitisation and challenge-proven allergy to the westernised countries which led the allergy epidemic. Ethnic differences in the sensitisation-allergy patterns are demonstrated in significantly higher fall-off in sensitisation versus allergy in the Xhosa patients compared with Mixed race. Study results show that risk factors for food allergy in this population include: early onset eczema < 6 months of age more severe eczema. Only half of sensitised patients with AD are allergic, hence oral food challenges play a crucial role in equivocal cases. 3. Where to from here? Following the significant results of food allergy prevalence in this population of high risk children, we are now planning a large food allergy prevalence study in an unselected population of 1-3 year old South African children, with the aim of also addressing rural-urban differences and patterns in different ethnic groups. The results of this forthcoming study will provide important data on the possible food allergy epidemic in South Africa, which will allow more targeted and informed planning of healthcare services. In the mean time, the results of our eczema-allergy study are initial evidence for an increase in food allergy prevalence in South Africa and indicate that a significant increase in disease burden may be imminent, especially in the context of rapid urbanisation and westernisation and subsequent changes in diet and lifestyle. The South African population-previously protected from the food allergy epidemic- provides a platform for understanding factors which may influence the expression of food allergy in the current food allergy epidemic. Such an understanding will hopefully eventually help us to modulate early determinants to try and curtail the development of allergic disease. References: 1. Grundy J, Matthews S, Bateman B et al. Rising prevalence of allergy to peanut in children: data from 2 sequential cohorts. JACI 2002; 110:784-89 2. Prescott S, Allen KJ. Food allergy: riding the second wave of the allergy epidemic. Pediatr Allerg Immunol 2011; 22: 155-60 3. Zar HJ, Ehrlich RI, Workman L, Weinberg EG. The changing prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema in African adolescents from 1995 to 2002. Pediatr Allergy Imunol 2007;18: 560-5 4. Mercer MJ, van der Linde GP, Joubert G. Rhinitis (allergic and non allergic) in an atopic paediatric referral population in the grasslands of inland South frica. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1989: 503-512 5. Levin ME, Le Souef PN, Motala C. Total IgE in urban black South African teenagers: the influence of atopy and helminth infection. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2008; 19: 449-54 6. Potter PC, de Longueville M. Sensitisation to aero-allergens and food allergens in infants with atopic dermatitis in South Africa. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2005 18 (3): 131-132. 7. Van Ree R, Yazdanbakhsh M. Allergic disorders in African Countries: linking immunology to accurate phenotype. Allergy 2007;62:237-40 8. Gray C. A prospective descriptive study to determine the prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy in South African children with atopic dermatitis attending a tertiary medical centre: Review of the first 80 patients. Abstract. South African Journal of Child Health 2011; 5 (3): 99