1 It`s a waste of time teaching grammar

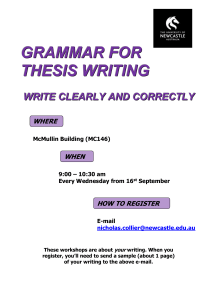

advertisement

Grammatical Functions and Categories

1

Part 1: Introduction

1. Linguistics, grammar, morphology (morphosyntax), and parts of

speech

1.O. Overview: Linguistics, its branches and subject matter

How can we define our subject matter in the present book and place it in a broader

context? It is obvious that grammatical categories and functions have something to do

with grammatical description, i.e. with grammar. It stands to reason to assume that

grammar, because it deals with language, must somehow belong to linguistics.

Grammar is thus part of linguistics, i.e. a part of the study of language in general that

aims at a self-contained description of language facts, and which has its own

methodology and terminology. Grammar can thus be thought of as a part of linguistics,

roughly speaking as that branch of lingustics that deals with the organization of

linguistic units into words and sentences. It is in this respect different from phonology,

which is concerned with sounds, and from lexicology, which is primarily concerned

with words as labels for extralinguistic phenomena.

Unfortunately, grammar is a fairly broad term, its uses ranging from the rather literal

one on the one hand, namely a handbook in which you can check how to use certain

language forms, i.e. a sort of language hardware, to quite complicated and tricky uses on

the other hand, e.g. referring to a sort of theory, or software for producing and

interpreting utterances of a given language, i.e. a set of rules. These rules can be thought

of as being internalized in the minds of native speakers, as well as being internalized in

a social code that holds together a linguistic community. In other words, grammar in

this sense is a kind of linguistic ability or competence possessed by native speakers. The

term grammar can also be used to refer to the actual application of these rules in speech,

for example in a statement like:

(1)

His grammar is bad.

In the latter case, grammar is equated with performance of native speakers.

There is one more meaning of the word grammar: a more or less systematic study of

the above mentioned rules, i.e. a discipline concerned with the description of the

structure of a given language. In this rather narrow sense of the word grammar,

2

Part 1: Introduction

grammar is limited to the morphology and syntax of a language and this is what we

shall be doing in this book for most of the time.

The approach to the structure of language can basically be of two kinds: You can

assume that the rules of grammar are discrete and fixed, that some forms are better than

others. This is the prescriptive or normative approach. It usually reduces grammar to a

list of rules that should be adhered to.

The other possibility is to observe and record what is actually used by speakers or

writers of that language. This is referred to as descriptive approach. To put it differently,

a descriptive grammarian attempts to describe the mechanisms according to which

language works when it is used to communicate with other speakers.

In a book like the present one, which is intended for non-native speakers of English,

we are forced to take a middle-of-the-road position on this issue, i.e. both descriptive

and to an extent prescriptive. If we take for granted that every English utterance we hear

or see produced by native speakers is acceptable or grammatical we will soon find out

that these native speakers sometimes mislead us (after all everybody can make mistakes,

not only learners of English as a foreign language). Since we cannot always judge what

is correct, we shall make reasonable use of statements based on a number of established

authorities, i.e. some traditional grammatical rules.

Many of the facts we are going to mention are widely familiar, but we are going to

try to place these phenomena in a broader perspective and systematize the previously

acquired knowledge. On the other hand, we will try to make rules behind them as

explicit as possible, i.e. learn to state or describe what is going on, and analyze these

phenomena. In other words, one should not only learn how to make use of certain

grammatical structures, to get acquainted with grammatical rules, but also become able

to talk about these structures and the rules behind them, as teachers are expected to do

when they explain them to their students. This means that one should acquire not only

language facts but also a sort of metalanguage (language used to talk about language),

i.e. linguistic terminology and, in a sense, a certain way of thinking about language.

Grammar as a study of rules at work in a language is again a very wide subject; it

deals with combinations of linguistic units of different size. The part of grammar which

deals with sentences and its parts such as subject, object, etc. is called syntax.

The part of grammar that concentrates on the form of basic linguistic units and their

variation, i.e. the distribution of their forms as well as, to an extent, with their

combinations, is called morphology. This is what we shall be studying in the present

book - linguistic units below the clause and sentence level.

The root of the word comes from Greek, where morphe means 'form', morphology

thus being study of forms. But what forms? It is customary in linguistics to distinguish

units even smaller than words: morphemes. They are defined as the smallest meaningful

units. They can be of two kinds: lexical morphemes like house, doll, horse, etc. or

grammatical ones like the endings -s, -ed, etc. Since, however, words in the English

language very often consist of one morpheme only, morphology is sometimes referred

2

Grammatical Functions and Categories

3

to as the study of word forms. Properly speaking, it is the study of the way morphemes

combine or change. We will be studying the way these grammatical morphemes

combine with lexical ones and/or with other grammatical ones.

Since English is, unlike Croatian or German, very poor as far as the inventory of

grammatical morphemes is concerned, we can allow enough time to study the way

certain words or combinations of morphemes are used in sentences and speech. We may

therefore claim that we in fact will be doing morphosyntax.

The term MORPHOSYNTAX is used to refer to a study of grammatical categories or

properties for whose definitions criteria of morphology and syntax both apply, as in

describing the characteristics of words. The distinctions under the heading of number in

nouns, for example, constitute a morphosyntactic category: on the one hand, number

contrasts affect syntax (i.e. singular subjects require a singular verb), on the other hand,

they require morphological definitions (e.g. add -s for plural). Further examples are

traditional categories such as passive, indicative, etc.

In the present context, the fact that we will be doing morphosyntax also means that

we will not concentrate only on morphemes, i.e. forms. We will try to link forms and

their meanings, i.e. account for the way these smallest or basic forms and their

combinations function in the English language.

Why is it still plausible to assume words as our starting point? Purely grammatical

morphemes rarely appear alone, they rather tend to stick to lexical ones. It is therefore

still plausible to assume words as our starting point. According to certain common

features the whole mass of words of a language lends itself to classification under

several broad headings such as nouns, verbs, adjectives etc. The number of such classes

may vary for different languages, but also depend on the particular grammatical

approach adopted by the linguist. These common grammatical features that word classes

exhibit are traditionally called grammatical categories. Thus, verbs can be described

with reference to categories such as tense, mood, voice, and aspect. Nouns, on the other

hand, can be discussed in terms of categories such as number, case and gender. This

accounts for the first part of the title of the present book.

The second part of the title, grammatical functions, has to do with the fact that it is

sometimes extremely difficult to determine whether a given word is a noun or verb, etc.

if no context is provided (e.g. can, hand, knife). Since this is possible only in actual

speech, i.e. in a context, the traditional term parts of speech (partes orationes in Latin)

seems to be well suited to English. Words belonging to certain classes can perform

specific functions within units of higher level, i.e. in phrases, clauses and sentences.

Verbs are thus typically central elements in the predicate of a clause.

Following traditional analyses, we will assume 9 such word classes or parts of

speech in English:

1. verbs

2. nouns

3. pronouns

6. adverbs

7. prepositions

8. conjunctions

4

Part 1: Introduction

4. articles

5. adjectives

9. interjections

The two volumes of the present book shall discuss only the first six of these.

1.T. Topics for further discussion

1.T.1. The internal structure of words: morphemes and morphs

If morphology as a linguistic discipline is traditionally defined as the study of word

structure, it follows that words are structured, complex units. What is the most

appropriate unit of measure/study of this complexity of structure?

By segmenting portions of language until no forms are found within the resulting

segments that have a constant meaning, we arrive at MORPHEMEs as smallest

meaningful units in the composition of words:

(1)

a. {catch} + {ing}

b. {catch} + {er}

Morphemes in isolation are technically represented in braces, square brackets or

capitals:

(2)

a.{tree}, {catch}, {er}

b. [TREE]

Morphemes within words may also be separated by stops, for purposes of their visual

representation:

(3) mis.lay.ing

Morphemes are abstract units that are realized by MORPHs.

1.T.2. Types of morphemes

There are several criteria for distinguishing the types of morphemes:

4

Grammatical Functions and Categories

5

i. their meaning/function: lexical vs grammatical

ii. independent status: free vs bound

iii. relative position

(4)

a.

morphemes

lexical/semantic

free

ROOTs/

STEMs

{chair}

grammatical/functional

bound

AFFIXes

ROOTs

free

function words

{the}

bound

AFFIXes

{-s}

{-ed}

PREFIXes SUFFIXes

{un-}

{dis-}

(4)

b.

{-ly}

{-ish}

{cran-}

{-fer}

cranberry

induce, introduce, reproduce

1.T.3. Allomorphs as alternative realizations of morphemes

Allomorphs are morph families whose members are positional alternants, i.e. they

have identical meaning but are in complementary distribution, i.e. their appearance is

conditioned phonologically, grammatically or lexically:

(5)

morpheme: NOUN PLURAL

morph: {z}

a. phonologically conditioned allomorphs: /z/, /s/, /z/

b. grammatically conditioned allomorphs: weep vs wep.t

c. lexically conditioned allomorphs: ox.en, kibbutz.im

If the allomorphs realizing a morpheme show no phonetic similarity, we speak of

SUPPLETION.

(6)

a. good vs better

b. go vs went

6

Part 1: Introduction

1.R. Readings

1.R.1. Recommended reading

Greenbaum, S., R. Quirk (1990: 1.2-5, 2.6)

Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum (1973: 2.12-13)

1.R.2. Further reading

Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, J. Svartvik (1985: 1.13-18, 2.3)

1.R.3. Sample texts for discussion

1.R.3.1. Ronald Wardaugh: Understanding English Grammar. A Linguistic Approach.

Oxford – Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1995, pages 5-7.

There is a longstanding tradition which says that there are eight parts of speech in

English: nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, and

interjections. In one variation of this tradition nouns are said to be the names of persons,

places, or things, e.g., man, city, tree, courage, nothingness; pronouns are said to be

words that can replace nouns or be used instead of them, e.g., he, someone, who; verbs

make predications or denote actions or states of being, e.g., sell, leave, become, appear,

be; adjectives modify nouns (and sometimes pronouns), e.g., big, alive, principal;

adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs, e.g., very, not, quickly; prepositions

indicate relationships between the nouns or pronouns that they are said to govern and

some other part of speech, and are words like at, in, under; conjunctions join clauses

together, e.g., and, until, when, because; and interjections express some kind of

emotion, e.g., Oh!, Ouch!, Alas!

There are many difficulties with this kind of classification. First, for the most part it

is meaning-based: what exactly are "names," "actions," and "states of being"? Second, it

combines statements about meaning (e.g., "nouns are names") with statements about

distribution (e.g., "adjectives modify nouns") and when these conflict offers no

guidance as to whether meaning takes precedence over distribution or distribution over

meaning. For example, is brick a noun in a brick because it names something and an

adjective in a brick house because of its distribution as a modifier of house? Third, it

6

Grammatical Functions and Categories

7

groups words which have very different characteristics into the same class, particularly

into the class of adverbs. If very, not, and quickly do have certain similarities, what

exactly are they? Finally, it ignores the many structural features of the language that

might be useful for classificatory purposes, e.g., characteristic word endings, how

phrases are built up, and how clauses are formed.

Some examples will be useful in further showing the inadequacies of many

traditional definitions of the parts of speech. What does emptiness name in Its vast

emptiness amazed him? What noun does nobody replace in Nobody succeeded in

solving the problem? Why exactly is swim a noun in the sentence He had a good swim

and a verb in the sentence It's good to swim in? In I found John's hat outside, what is

John's, a noun or an adjective? If old and stone are said to be adjectives in an old wall

and a stone wall, why is it possible to say a very old wall but not *a very stone wall?

(The *indicates that what follows is ungrammatical in English.) Is it because certain

adjectives must follow other adjectives when they are combined in phrases, or is it

because stone is not really an adjective at all but is a noun that modifies another noun

and therefore must follow an adjective that modifies that same noun? Note that in a

sentence like When the young girl entered, I gave her the parcel, the pronoun her does

not replace a noun (girl) but rather a noun phrase (the young girl). Not, quite, and there

are all said to be adverbs in It's not quite there, but what other possible uniting feature

do they have except that they do not fit into any of the other categories? To say that

something is an adverb is really to say little more than it is not an adjective, conjunction,

preposition, etc.

In a structural classification of the parts of speech in English there are two basic

approaches to the categorization of words. One is to look at the forms of the words

themselves in order to find out what structural characteristics they have and what kinds

of changes occur as they are used in phrases, clauses, and sentences. In this approach we

look at words in isolation in order to see what their formal characteristics might tell us

about them: cat has another form cats, bite has the forms bit and bitten, and big has both

bigger and biggest. (Of course, if words have no special formal characteristics, as the,

very, must, in, etc. do not, such an approach is inherently limited.) The other approach,

therefore, is to look at the distributions of words in the belief that words that regularly

fill the same slots in basic recurring patterns in the language, e.g., as subjects, objects,

complements, etc., may be said to belong to the same general category. In this way we

will find that cat distributes like plate, bite like take, big like old, and so on. We will

also find with words that show no changes in their forms that the distributes like a, very

like rather, must like can, in like under, and so on. Let us now look at these two

approaches in some detail.

By formal characteristics, we mean the characteristic inflectional changes or the

characteristic word endings (derivational endings) that we observe in sets such as the

following:

Inflections

Derivations

cat, cats, cat's, cats'

I, you, he, she, it, we, they

judgment, kingdom, baker

himself

8

Part 1: Introduction

bake, bakes, baking, baked

long, longer, longest

synthesize, pacify

topical, smallish, hopeful

We can then use the terms noun, pronoun, verb, and adjective respectively for typical

members of each of the above rows. (We will continue to use traditional labels

whenever they are useful.) As we will see, many English words are without inflectional

or derivational marking. Consequently, the part-of-speech categorization of such words

must require the use of some other criterion or characteristic.

By using distributional criteria, we mean the single words that can be inserted into

slots such as those marked by X in each of the following sentences:

He bought the X.

He wants to X.

The boy is very X.

He went X.

X: man, dog, butter, paper

X: dance, leave, sing, cook

X: tired, young, pleasant, bright

X: out, in, quietly, there

In this case single words that typically occupy the four slots can also be named noun,

verb, adjective, and adverb respectively. However, there are many other possible

distributions in the language and it is quite easy to show that when the distributional

possibilities of words are taken into account, we must recognize a great many different

parts of speech in English. We will also need to acknowledge that some words move

easily from one grammatical category to another and that some are even unique in how

they are used in the language.

1.R.3.2. Talmy Givón: English Grammar. A Function-Based Introduction. Part I.

Amsterdam – Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1993, pages 46-49.

In addition to their divergent functions, other criteria may be used to distinguish

lexical words from grammatical and derivational morphemes. In English, these criteria

are:

criterion

lexical words

non-lexical morphemes

morphemic status: free

word size:

large

stress:

stressed

meaning:

complex, specific

class size:

large

membership:

open

function:

code shared knowledge

We will survey these criteria in order.

8

bound

small

unstressed

simple, general

small

closed

grammar, word-derivation

Grammatical Functions and Categories

9

a. Morphemic status:

Lexical words tend to come as free, independent words. Grammatical and

derivational morphemes tend to appear as bound morphemes or affixes. They are

attached to lexical words as either prefixes or suffixes.

b. Word size:

Lexical words tend to be large (long). Grammatical and derivational morphemes tend

to be small (short).

c. Stress:

A lexical word in English carries one primary word-stress. Grammatical and

derivational morphemes tend to be unstressed.

d. Meaning:

Lexical words tend to be semantically complex; that is, they are clusters of many,

highly specific semantic features. Each lexical word is thus a member of many semantic

fields. Grammatical and derivational morphemes, on the other hand, tend to be

semantically simple; they often code a single feature, one that is likely to be very

general ('classificatory').

e. Class size:

Lexical words come in few large classes. Grammatical and derivational morphemes

come in many small classes.

f. Membership:

The membership of a lexical class is relatively open; new members join regularly and

old members drop out, as new words are coined or the meaning of old words is

extended. Cultural change is the prime cause of addition or subtraction of lexical

vocabulary. The membership of a grammatical or derivational class, on the other hand,

is relatively closed, and grammatical change is usually involved when members are

added or subtracted. Most commonly, grammatical change involves changes in the

communicative instrument itself, rather than in the cultural world-view. Such changes

tend to occur under three distinct functional pressures:

(a) Creative elaboration of the code

(b) Truncation of code elements for faster processing

(c) Simplification of the code: message relation

g. Historical origin:

10

Part 1: Introduction

The lexical words of English, as noted earlier above, are both native Germanic and

borrowed. This is also true of English derivational morphemes, which were borrowed

together with lexical words. In contrast, English grammatical morphemes are all native

Germanic.

1.E. Exercises

1.E.1 Examine the following statements. They have all been made at one time or

another by teachers and learners of English.

1 English is a very irregular language. It is therefore difficult for a non-native speaker

to learn.

2 When a native speaker and a non-native speaker of English converse in English, this

is an authentic use of the language by both parties.

3 The British/Americans seem very tolerant of non-natives' use of English. It is thus

difficult for the non-native speaker to get feedback on whether or not they are using

English correctly when speaking to a native speaker of English.

4 If a person does not know English, it will be difficult for that person to participate in

today's world.

5 Without a knowledge of grammar, it is difficult to see a student progressing in their

learning of a language.

6 Memorizing lists of words out of context is not a particularly helpful learning

strategy for the non-native speaker.

1.E.2. Which of the attitudes about teaching and learning grammar as expressed

below is: (i) most similar to your own: (ii) most different from yours; (iii)

most common in your community.

1 It's a waste of time teaching grammar - it only confuses the students and uses up

valuable class time which we could be using for the teaching of skills.

2 Without grammar, there is no language learning. It is the backbone of the whole

process.

3 Although we need to be aware of the importance of grammar, we should not teach it

directly. It is best learned by indirect exposure to the target language.

4 Grammar is the only part of a language which we can be sure about; to ignore it is a

sort of madness.

5 If we are teaching students to communicate, grammar is of no real use.

1.E.3. Match the items in the left-hand column with the items in the right-hand

column in order to create a matrix of terms to describe language and its

components, patterns and systems. Give one or two examples of each. Note

10

Grammatical Functions and Categories

11

any of the elements in the right-hand column that cannot be qualified in any

way with an item from the 'type' column.

Type

transitive

count

prepositional

intransitive

infinitive

finite

nonfinite

definite

generic

reflexive

personal

mass

abstract

collective

conditional

causal

Element

pronoun

gerund

verb

phrase

noun

adverb

article

preposition

clause

1.E.4. Identify the morphemes in the following and determine which ones are free,

and which ones are bound. In some cases the choice will not be clear-cut.

Explain the grounds for your decision.

beds

bedding

bedrooms

bed-sitter

baby-sitter

baby-sit

servility

servant

server

manly

mannish

manhood

manager

management

mismanagement

easy-to-do

red-head

red-handed

foothold

footpath

footlights

footman

footsteps

footloose

bittersweet

maidservant

hobnob

1.E.5. How many of the words in sentences a. and b. below contain more than one

morpheme?

a. No Englishman is ever fairly beaten.

b. One should not be too severe on novels; they are the only relaxation of the

intellectually unemployed.

1.E.6. Which word classes (noun, verb, etc.) do each of the words in the list below

fall into? More than one class is possible for most items.

12

Part 1: Introduction

watch

himself

onto

me

red

well

laughing

go

bigger

attack

slick

smart

bounce

chart

one

goal

however

upwards

in

sun

will

1.E.7. Classify the italicised words as parts of speech. If a word is italicised more

than once, e.g. right, refer to the first occurrence of as right (1), the second

as right (2), and so on.

1 Is it right to say that right wrongs no man?

2 One cannot right all the wrongs in the world.

3 Cure that cold with a drink of hot lemon before you go to bed.

4 Drink this quick! Don't let it get cold.

5 Before the Fire, there had been a plague, the like of which had not been known before

and has not been seen since.

6 It is a common failing to suppose we are not like other men, that we are not as other

people are.

7 As your doctor, I must warn you that the results of taking this drug may be very

serious.

8 Growth in weight results in the development of muscles and fat.

9 Warm pan, sift dry ingredients and stir well.

10 Dry hair thoroughly with warm towel and comb.

1.E.8. Form verbs from the stem by adding -ize or -ify. Find nouns related to these

verbs.

quantcomputerelectrstylpersonpersonalliqudiversminim-

idolsolidliquidmoralfalsindemntestintensmobil-

1.E.9. Add one of the prefixes below to the verb in brackets and replace the

italicised words , making other necessary changes.

re-

over-

under-

un-

mis-

1 I do not like food which has been warmed up a second time. (heat)

2 We have been asked to pay too much for this wine. (charge).

3 This steak is too rare in my opinion. (cook)

4 He took everything out of his suitcase. (pack)

12

Grammatical Functions and Categories

13

5 I was wrong in my estimate of the cost of our holiday. (calculate)

6 The army forcibly removed the elected government. (throw)

7 He gave back the money he had borrowed. (pay)

1.E.10. The ending -ate may be pronounced [eit] or [t] depending on the way the

word is used. How is it pronounced in each of the sentences below? Is

there any link between the word class and the pronunciation?

1 I estimate we will be there by 6.

2 She made an appropriate reply.

3 The design proved to be too elaborate.

4 Please moderate your language.

5 Don't let the meeting degenerate into a row.

6 It was a deliberate attack on the government.