CS XIII - CARE International`s Electronic Evaluation Library

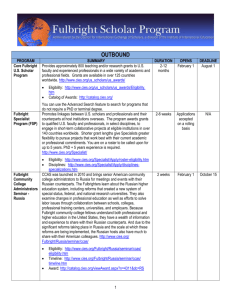

advertisement