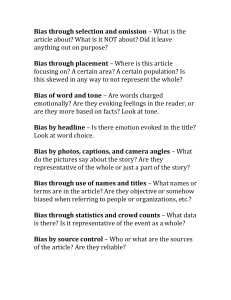

Bias by Holly Stout - The Constitutional & Administrative Law Bar

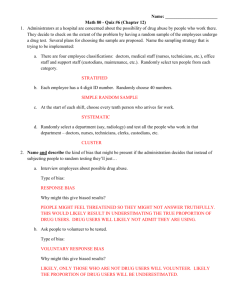

advertisement