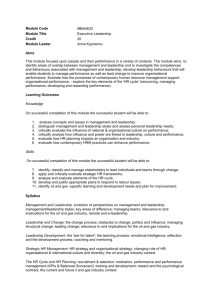

For no - Cultures of Consumption

advertisement