- ABC Coaching and Counselling Services

Chapter 10: The "Individual" and its Social

Relationships - The CENT Perspective

Summary

This chapter begins with a recapitulation of the author’s approach to rethinking the model of the human individual implicit in Rational

Emotive Behaviour Therapy, using some of the core concepts of

Freudianism to provide a structure. Next, the text returns to

Freud’s writings to review some of those concepts, and in particular to challenge Feud’s view of human sexuality. The result is a more general view of power relations between children and parents, and emotional difficulties arising out of those conflicts, rather than through psychosexual stages of development.

The text then reviews the theory and perspective of the Object

Relations school of psychology/psychotherapy. This psychodynamic orientation sees relationship as being central to what life is about.

It is not an optional extra. Human babies are ‘born to relate’.

Relationship is integral to the survival urges and survival strategies of humans. The CENT perspective sees the relationship of motherbaby as a dialectical one of mutual influence, in which the baby is

‘colonized’ by the mother/carer, and enrolled over time into the mother/carer’s culture, including language and beliefs, scripts, stories, etc. This dialectic is one between the innate urges of the baby and the cultural and innate behaviours of the mother. The overlap between mother and baby gives rise to the ‘ego space’ in which the identity and habits of the baby take shape. And in that ego space, a self identity appears as an emergent phenomenon, based on our felt sense of being a body (the core self) and also on our conscious and non-conscious stories about who we are and where we have been, who has related to us, and how: (the autobiographical self).

Section 5 explores the question ‘Who am I?’ and in the process structures a model of what a human individual seems to be. And

Section 6 examines the nature of good and evil, as innate and socially constructed aspects of each individual, including supporting evidence for this perspective in the literature of different religions and cultures.

This is followed by a brief review of the philosophy and psychology of human development, from Plato, though Kant, to Piaget, Bruner and Vygotsky; and back to Freud and the Object Relations theorists.

Section 9 reviews the way in which Transaction Analysis can be used to conceptualize the internalization of the mother and father by the baby’s mind. And, finally, Section 10 explores how the

(conscious and non-conscious) mind emerges from the complexity of internalized relationship experience.

~~~

1. Introduction

Somewhere around the beginning of 2009, I was working on the development of a set of models that were taking shape as the core of Cognitive Emotive Narrative Therapy (CENT). I had reviewed my earlier work, from 2003, on the complex A>B>C model and was still unhappy with the way the "individual" shows up in my models as isolated and separate from others. (See the models in Chapter 2, above).

I had begun with the Stimulus-Organism-Response model, and then built up a model of the A>B>Cs which included overlapping cognitions and emotions at point B in that model, as follows:

Figure 1 - A complex A>B>C model

In this model, the beliefs are assumed to be in the head of an individual. However, in Figure 3 of Chapter 2, above, I did say that the Activating Stimulus (A1) is "socially agreed". Nevertheless, how this social agreement comes into effect, or gets represented at point

B in the model – as part of the ‘individual’s belief system’ - was not discussed in that chapter.

Much later in that chapter, I went on to present a model which takes account of the body of the individual, as follows, but still no real social dimension. This linking of the body and mind echoes the arguments in Damasio (2000) 1 .

Figure 2: The A>B>C Model Related to the Y-Model

Figure 2 shows a weight lifter, thinking-feeling-behaving in relation to his task. This image suggests that, when something happens at

A1, it is interpreted at A2 (not shown), which triggers cognitiveemotive processing of the A2 signal at B (1, 2 and 3). At the same time, the B1 (unconscious cognitive-emotive processing) sends a signal to the Y-model (visceral, facial, physiological arousal), which responds by sending a signal to the C1 (not shown) where it combines with the output from B, and together these signals produce the emotional-behavioural response at C. As it stands this could seem to be a fairly straight restatement of the James-Lange theory of emotion. (Kagan and Segal, 1992, pages 321-322).

However, this still shows no connection of the individual to the social background from which s/he sprang; although it does show his/her current connection to his/her environment (via the A1, or

1

Damasio, A.R. (2000) The Feeling of What Happens: body, emotion and the making of consciousness. London: Vintage.

Activating Stimulus), which in this case is assumed to be external.

(Sometimes the Activating Stimulus is internal: a memory from the past; or an anticipation of some future event).

I had lived my own life - at least up to the age of thirty, and a little beyond - as an (emotionally) isolated individual who did not understand relationship - or so it seemed to my analyst and me

(back in 1968) - and yet I now (1980 onwards) knew from Zen philosophy that every "thing" is just a small distinction within

"everything". In other words, Zen sees the individual as being

distinguished from, but not separate from, everything else.

There is only one "life" and it is all of a piece. So why did my psychological models show "separate individuals"?

I had written to Dr Albert Ellis (probably around summer 2000) to say that, because REBT did not have a personality theory, I normally used Transactional Analysis (TA) when trying to understand the personality structure of my clients. TA postulates that we each have a number of ego states (or cognitive/ emotive/

behavioural states), primarily the Parent, Adult and Child ego states; and that our current thinking, feeling and behaviour is determined by whichever ego state we are ‘occupying' (or ‘acting from') at any particular point in time 2 . However, I still could not quite see how the TA Ego State model could be incorporated into the A>B>C> model of REBT; and I kept returning to that challenge from time to time. (This will be described in detail in Section 7 below).

2. Back to Freud

Somewhere around Easter 2009, I returned to reading some of

Freud's papers to see if I might find some clues there. See in particular Freud (1940 [1938]) 3 , and his papers in Gay (1995) 4 .

2

In TA theory, we assume that, at any moment in time, an individual will be thinking, feeling and acting just like s/he once did as a child (Child ego state); or thinking, feeling and acting like some parent figure from his/her past (Parent ego state); or coolly calculating the pros and cons of her current reality (Adult ego state). See

Stewart and Joines (1987) – (Stewart, I. and Joines, V. (1987) TA Today: A new introduction to Transactional Analysis. Nottingham and Chapel Hill: Lifespace

Publishing.)

3 Freud, S. (1940 [1938]) An outline of psychoanalysis. In: Sigmund Freud (1993)

Historical and Expository Works on Psychoanalysis. The Penguin Freud Library,

Vol.15. London: Penguin Books.

4

Gay, P. (ed) (1995) The Freud Reader. London: Vintage Books.

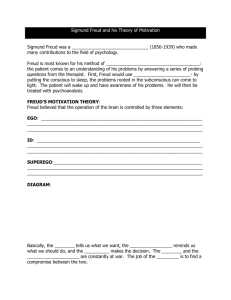

Freud's model of the psyche, or mind of the human, has three essential parts:

1. The "it", or the physical/psychic baby, just as it is born, with no cultural experience. This was translated as "the id" by his English translators. (The "it" is not a "who", which it will eventually generate through cultural experience).

2. The "I", or "ego", which begins to emerge from the id when the baby is a few months old, as a result of social contact with the mother (or mother substitute). (Cf: Gay, 1995: 724-725).

3. The "over-I", or "superego", which emerges because the ego internalizes social rules and expectations. The superego is the seat of the conscience, and also includes the self ideal, or "what I should become or be".

Here is how Freud imagined those three elements of the psyche to be interrelated. (This model originates in Freud, 1933) 5 .

Figure 3: Freud's model of the psyche

5

Freud, S. (1933) ‘The Anatomy of the Mental Personality': A lecture. In: New

Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis . Hogarth Press. Available online at: http://traxus4420.wordpress.com/2007/11/ . Accessed: 18 th

December 2009.

In this model, the id is shown to be unconscious, which is an unfortunate term that I find quite confusing. We normally think of somebody who has been knocked out as being "unconscious". And by that we mean, incapable of functioning as a normal human

agent. However, what Freud meant by the "unconscious" was actually "non-conscious processing"; in so far as it was possible to reach that conclusion in his era 6 . That is to say, a part of our mind processes information in ways that help us to adapt and adjust to external reality - the ‘adaptive unconscious' - without any conscious awareness arising within us that this processing is occurring. (See

Gladwell, 2006 - below - for further elaboration of this concept of

‘adaptive unconscious'). When Freud proposed the "unconscious mind", he was derided by philosophers, who considered any mental processing to be necessarily conscious. (Freud, 1995:19) 7 .

However, there is much modern evidence for the existence of non-

conscious information processing, as an essential explanation for human functioning. (Cf: Bargh and Chartrand, 1999 8 ; Gladwell,

2006 9 ; Gray, 2003 10 ; Maier, 1931 11 ; and Haidt, 2006 12 ). I explored that evidence in my doctoral thesis 13 , and summarized much of the

6

What he actually said and wrote was this: "The oldest and best meaning of the word

'unconscious' is the descriptive one; we call 'unconscious' any mental process the existence of which we are obliged to assume - because, for instance, we infer it in some way from its effects but of which we are not directly aware." (Freud, 1933: available online, as above).

7

Freud, S. (1995a) An autobiographical study. In: Peter Gay (ed) The Freud Reader.

London: Vintage Books.

8

Bargh, J.A. and Chartrand, T.L. (1999) The unbearable automaticity of being.

American Psychologist, 54(7): 462-479.

9

Gladwell, M. (2006) BLINK: The power of thinking without thinking. London:

Penguin Books.

10 Gray, J. (2003) Straw Dogs: thoughts on humans and other animals. London:

Granta Books.

11

Maier, N.R.F. (1931) Reasoning in Humans: II - The solution of a problem and its appearance in consciousness. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 12: 181-194.

12

Haidt, J. (2006) The Happiness Hypothesis: Putting ancient wisdom and philosophy to the test of modern science. London: William Heinemann.

13 Byrne, J.W. (2008) Teaching and Learning Ethical Research Competence in

Qualitative Research: An Action Research Inquiry: A thesis submitted to the

University of Manchester for the degree of Professional Doctorate in Counselling in the Faculty of Humanities. Manchester: School of Education, University of

Manchester. Available online: http://www.abc-counselling.com/id205.html

.

results in Byrne (2009e) 14 , and Chapter 9 above. Here is a brief summary of the main point of Byrne (2009e):

I argued that humans are both conscious (a small amount of the time) and non-conscious (about 95% of the time), and this is unavoidable because of the strictly limited ‘bandwidth of conscious processing’, which restricts us to about one millionth of the data we daily use (non-consciously) to survive. (Gray, 2003: 66) So my research respondents - and my CENT clients - are probably unconscious (meaning nonconscious processors of information) for at least 95% of the time, including most of the time they are interacting with me.

Returning to Freud's model of the psyche, above, we can see that the ego straddles the unconscious, the pre-conscious and the conscious. The conscious is what we are aware of, and the preconscious is what we can readily become aware of. There is also a division on the right of the model which represents material which has been repressed out of conscious awareness, into unavailable unconscious material.

On the left hand side of Figure 3 we see the division called the super-ego (or over-I), which is the internalized moral codes of the parents and significant others, and the models of an ideal self which are both taken over from parents and others, and self constructed.

Although this model does contain this internalized social influence, the model still feels and looks like a model of an isolated individual, cut off from the world.

The next model I want to consider is a more detailed version of

Freud's original model. It's normally referred to as the ‘iceberg model':

14

Byrne, J. (2009e) The status of autobiographical narratives and stories in CENT.

CENT Paper No.5. Hebden Bridge: The Institute for CENT Studies. Available online: http://www.abc-counselling.com/id167.html

.

Figure 4: The iceberg model (By Anthony A. Walsh) 15

This version of the model provides more detail than Figure 3, above. The super-ego is shown as the ‘social component' of the individual. The ego is labelled as the ‘psychological component'.

And the id is shown as the ‘biological component'.

Freud had begun by seeing the id as biological, and all of its fragmentary developments, including ego and super-ego components, as being driven by biological urges or drives.

In theory, Freud's model could have been developed to inquire into how the socialization processes in general resulted in a particular kind of ego development; how tensions could build up between the three components of the model from many sources to do with power, distorted perceptions, maladjustment of relational factors between parents and their children; and so on. However, Freud narrowed his focus down to one phenomenon: the sexual history, and especially sexual maladjustments. This is how he announced his conclusion:

15

Walsh, A.A. (2009) The influences on surrealism. Available online at: http://www.tcf.ua.edu/Classes/Jbutler/T340/freuds_model.jpg

. Accessed: 18 th

December 2009.

"I now learned from my rapidly increasing experience that it was not any kind of emotional excitation that was in action behind the phenomena of neurosis but habitual ones of a sexual nature, whether it was a current sexual conflict or the effect of earlier sexual experiences": (Freud, 1995) 16 . He then went back and reexamined his earlier patients records and concluded that: "I was ... led into regarding the neuroses as being without exception disturbances of the sexual function, the so-called ‘actual neuroses' being the direct toxic expression of such disturbances and the psychoneuroses their mental expression. My medical conscience felt pleased at my having arrived at this conclusion". (ibid, page

15).

This seems to me to be an overgeneralization of the most extreme kind. There are so many things, of a nonsexual nature, that can go wrong in the power relations between children and their parents, and children and their peers, that it is unthinkable that such malfunctions play no part in the development of emotional disturbances - all of which have already been accounted for by one source of disturbance - sexual experience. There is no doubt that sexual experiences of an unnatural or distressing nature must be

one of the sources of human disturbance; but only one. And I have no doubt that frustrations of the affectional/amorous and loveseeking urges of the child will often result in emotional disturbances.

Annoyingly, Freud goes on to redefine sexuality in a way that makes it virtually non-sexual - unconnected with the genitals, and incorporating "...all of those affectionate and merely friendly impulses" which we normally call love - which must thereafter logically include virtually all normal positive human motivations within his concept of sexuality. If sexuality is thus defined (by

Freud) as the virtual sum of positive human motivations - (plus a bit of the negative ones) - then sexuality becomes almost the only potential source of human disturbance; because sexuality has come to subsume almost everything that is characteristically human.

When Freud and (some) Freudians then say that all human disturbance is linked to sexuality, what they apparently mean is that all human disturbance arises out of their human urges to cathect (or grasp) elements of their world/environment. Or, slightly more generally, all human emotional disturbance is caused by being human and interacting in human ways with other humans. This explains nothing!

16 Freud, S. (1995a) An autobiographical study. In: Peter Gay (ed) The Freud

Reader. London: Vintage Books. Page 14.

Among Freud's followers there were some who could not go along with his psychosexual overgeneralization, and who wanted to take a more general view of human disturbance. Carl Gustav Jung and

Alfred Adler were amongst them. This is how Freud describes their deviations from his scheme:

"Jung attempted to give to the facts of analysis a fresh interpretation of an abstract, impersonal and non-historical character, and thus hoped to escape the need for recognizing the importance of infantile sexuality and the Oedipus complex as well as the necessity for an analysis of childhood. Adler seemed to depart still further from psycho-analysis: he entirely repudiated the importance of sexuality, traced back the formation both of character and of the neuroses solely to men's desire for power and to their need to compensate for their constitutional inferiorities, and threw all of the discoveries of psycho-analysis to the winds". (Freud,

1995, page 33).

I have to say that I agree with much of what is said by Jung and

Adler; and I am convinced that, though sensuality and a desire for love - and even the desire to ‘possess the mother', in a non-genital way - seems to be central to the motivations of all infants and toddlers 17 , the idea that every child experiences a full blown

Oedipus Complex seems like a gross overgeneralization. Power relations of a more general nature within the family seem to me to be a much more fruitful domain to investigate than sexual desire

per se. And this is the domain of the Object Relations school of post-Freudians.

(However, this sense of the centrality of relationship also seems to be broadly accepted by modern Freudians, as indicated by Storr

[2001: 38] 18 , when he says that: "Where Freud was wrong was in making psychosexual development so central that all other forms of social and emotional development were conceived as being derived from it. ... Today, most students of childhood development regard sexual development as only one link in the chain, not as a prime cause. Difficulties in interpersonal relationships may be derived from early insecurities which have nothing to do with sex, but which can cause later sexual problems..." Here, Storr betrays his overinfluence by Freud by omitting to say "and those early difficulties

17

Mahler, M.S., Pine, F. and Bergman, A. (1975/1987) The Psychological Birth of the

Human Infant: Symbiosis and individuation. London: Maresfield Library.

18 Storr, A. (2001) Freud: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University

Press. Page 38-39.

may also cause later non-sexual problems; and that most neurosis probably has little to do with sex per se!" Of course, we still have to accept that actual difficulties in the sexual development of an individual "...may cause subsequent social problems" 19 , which is a million miles from Freud's formulation.)

3. Object Relations

Throughout most of his career, Freud had emphasized the objective, biological nature of the psyche, or mind, and its innate urges or drives. However, towards the end of his life, he began to acknowledge the subjectivism of mind states, the role of experience in shaping the mind, and the importance of relationships between people/minds and the equal importance of relations between the elements or components of the mind. According to Gomez (1997:

3) 20 , "...the Oedipus Complex with its interpersonal structure, and the super-ego as an internalization of the parent, demonstrate the addition of a relational perspective to his earlier view that emotional development was based on endogenous (or purely internal) processes".

He also began to place more emphasis on the ego than on the id, and to look at splits in the ego. However, his awareness of splits in the ego goes back to at least 1909, when he presented his series of five lectures at Clark University at Worcester, Massachusetts. In his first lecture he said: "The study of hypnotic phenomena has accustomed us to what was at first a bewildering realization that in one and the same individual there can be several mental groupings, which can remain more or less independent of one another, which can know nothing of one another, and which can alternate with one another in their hold upon consciousness". (Page 43: Freud, S.

[1962] Two Short Accounts of Psycho-Analysis. Harmondsworth,

Middlesex: Penguin Books). This insight about splits in the ego had to await the arrival of Dr Eric Berne, in the 1940s and 50s for its full flowering into Transactional Analysis. (Games People Play, 1968) 21 .

Melanie Klein was the first major developer of this social relationship strand within Freud, but, given that she was not a scientist or medically trained, she developed a more subjective formulation of power relations in families than Freud could accept,

19

Storr (2001, page 39).

20 Gomez, L. (1997) An Introduction to Object Relations. London: Free Association

Books.

21

Berne, E. (1968) Games People Play: the psychology of human relationships.

London: Penguin Books.

and so he rejected her as yet another deviationist. Indeed, Klein's theory of ‘subject relations' between mother and child was so intuitive, so colourful and fanciful, that it could not be sustained in the longer term, for she attributed to the new born child the capacity to think in terms of ‘good and bad breasts', exchanges between mother and infant of ‘faeces, milk, penises and babies' and so on. But she opened the door to a more thorough break with

Freud's atomizing of the individuals in a group into separated, as opposed to merely distinct, parts. (Gomez, 1997: 29-53). And she began a movement towards empathic understanding of the emotionally painful nature of infancy.

Around the same time as Klein, Ronald Fairbairn began to write about the dynamic structure of the self. Rather than being rejected by Freud, Fairbairn rejected Freud's scientific premises, and argued that "...the purpose of life (is) relationship rather than the gratification of instincts", and "he proposed a model of the mind which did away entirely with Freud's biological foundations".

(Gomez, 1997: 3). It might have been more helpful if he had concluded that our basic instincts seem to drive us towards relationship. (‘Something’ arrives with the baby; some innerdirectedness; some urges, appetites, drives – some emotional wiring).

When I first read that statement that the purpose of life is relationship, in Lavinia Gomez's (1997) book, I began to think more dialectically about the relationship between mother and child. I saw

Freud's biological bias, and Fairbairn's psychological bias as just that: biases. It suddenly seemed intuitively obvious to me that

‘individual humans' are both biological and psychological; and also that ‘individual humans' begin their lives as totally dependent ‘social products'. At that point, I began to rethink my models of mind.

This is what I came up with (as presented in Byrne, 2009f) 22 :

22

Byrne, J. (2009f) How to analyze autobiographical narratives in Cognitive Emotive

Narrative Therapy. Hebden Bridge: The Institute for CENT Studies. Available online: http://www.abc-counselling.com/id173.html

.

Figure 5: The most basic model of CENT - The dialectical nature of the individual/social ego. The ego is a product of relationship, and cannot exist without (external and/or internalized) relationship

The (normal, ‘good enough') mother has no real choice but to

‘colonize' the new born baby, as it is totally helpless; and she is wired up by nature to become attached to her children. She must

‘march in', take over, and run the baby's life for ‘it', otherwise

(unless it is colonized by a mother substitute) it will surely die. The neonate, or baby, is also wired up by evolutionary forces to ‘seek' a connection with what must seem (physically, emotionally) to be

"another part" of itself: thus creating a ‘natural symbiosis' which satisfies some innate needs of the baby, and some innate and socially shaped needs of the new mother. (The urge to seek a breast and suckle seems to be innate to all mammals). (Taylor,

1999 23 ; Gerhardt, 2004 24 ; Lewis, Amini and Lannon, 2001 25 ).

Over time, the mother and baby interact, in what initially what may seem like a very one-sided relationship, but increasingly, over

23

Taylor, D. (ed) (1999) Talking Cure: Mind and methof of the Tavistock Clinic.

London: Duckworth.

24 Gerhardt, S. (2004) Why Love Matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain.

London: Routledge.

25

Lewis, T., Amini, F. and Lannon, R. (2001) A General Theory of Love. New York:

Vintage Books

weeks and months, a mutual (largely symbolic from the baby's side

[e.g. turning towards the mothers voice, smiling]) giving and taking develops.

Figure 6(a): The mother interacts with the baby, and the baby interprets and encodes the experience in its embryonic ‘ego' space

Actually, from the very beginning of extra-uterine life, the baby and mother become locked together by facial communication from the emotional centres of their brains. This is called “limbic resonance” by Lewis, Amini and Lannon (2001) 26 . Figure 6(a) shows the earliest moments and hours of mother/baby interaction, in which the mother is the active agent while the baby encodes the experience of being held, fed, washed, dressed, kissed, cuddled, etc. Those events are the foundation of the socialized child. This is when and how we learn to feel, to interpret and manage our feelings and the interpretations of experiences. This is how the attachment style of the baby is established – secure or insecure 27 .

26 Lewis, T., Amini, F. and Lannon, R. (2001) A General Theory of Love. New York:

Vintage Books.

27

Wallin, D.J. (2007) Attachment in Psychotherapy. New York. The Guildford

Press. Pages 11-13.

One feminist writer, quoted in Gerhardt (2004) 28 describes the experience of suckling her young babies:

“The bad and the good moments are inseparable for me. I recall the times when, suckling each of my children, I saw his eyes open full to mine, and realized each of us was fastened to the other, not only by mouth and breast, but through our mutual gaze: the depth, calm, passion, of that dark blue, maturely focussed look”. (Page 16).

The mother and baby are engaged in a form of nonverbal communication, between the limbic system (or emotional centres) of the baby’s brain and the limbic system (plus prefrontal cortex areas that manage emotions) of the mother’s brain. Lewis, Amini and Lannon (2001) 29 show how the baby is reassured and comforted by real-time feedback from the mother’s face, even via linked video cameras. However, if a delay in introduced into the mother’s responses, the baby becomes distressed.

There is no doubt that, from the beginning of life, the baby and mother are involved in an active emotional relationship what the baby is wired up to seek out. This is what these authors call “limbic resonance”: “A mammal can detect the internal state of another mammal and adjust its own physiology to match the situation – a change in turn sensed by the other, who likewise adjusts. While the neural responsivity of a reptile is an early, tiny note of emotion, mammals have a full-throated duet, a reciprocal interchange between two fluid, sensing, shifting brains”. (Lewis, Amini, and

Lannon, 2001: pages 62-64).

Later they say: “…emotionality forms a principal dimension of

(stored memories)… (A) particular emotion revives all memories of its prior instantiation. Every feeling (after the first) is a multilayered experience, only partly reflecting the present, sensory world”. (Page 130). In other words, our earliest emotional memories shape and colour the kind of subsequent emotional memories we can have!

Everywhere we go as humans, we engage in nonverbal communication with, and reading of emotion from, others in our environment. This process of limbic resonance is so silent and

28 Gerhardt, S. (2004) Why Love Matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain.

London: Routledge.

29

Lewis, T., Amini, F. and Lannon, R. (2001) A General Theory of Love. New York:

Vintage Books.

efficient that we hardly notice that it is happening. Nothing comparable happens from neocortex to neocortex. “…feelings are contagious while notions are not”. (Lewis et al, 2001, page 64).

And relationship is about mutual influence and shaping of the individual by its (or his/her) partner: “Long-standing togetherness writes permanent changes into a brain’s open book. – In a relationship, one mind revises another; one heart changes its partner. This astounding legacy of our combined status as mammals and neural beings is limbic revision: the power to remodel the emotional parts of the people we love, as our (Cumulative

Interpretative Emotional Patterns) activate certain limbic pathways, and the brain’s inexorable memory mechanism reinforces them. -

Who we are and who we become depends, in part, on whom we love”. (Lewis et al, 2001: page 144). And, of course, who we are, and who we become, depends upon who loves us, how much, and

how.

In the first four or five months of the new baby’s life, this relationship is apparently totally symbiotic, with the baby having no real sense of being a ‘separate being'. Around the fourth or fifth month, the baby begins to differentiate ‘itself' from ‘the other

(mother)': (Mahler, Pine and Bergman, 1975/1987, cited above) 30 .

When the baby gets past the symbiotic stage and becomes active, it

“…seeks out interaction with others, turns away from others when overwhelmed, freezes when he feels at risk; he already has the rudiments of emotion and self-regulation. Emotions are first and foremost our guides to action: they are about going towards things and going away from them”. (Gerhardt, 2004: page 33).

So from the very beginning, humans are social animals, and

Gerhardt (2004) says: “Human being are the most social of animals and are already distinctive in this way at birth, imitating a parent’s facial movements and orienting themselves to faces very early on”.

(Page 33).

However, I still could not quite see how the TA Ego State model could be incorporated into the A>B>C> model, and I kept returning to that challenge from time to time.

30

Mahler, M.S., Pine, F. and Bergman, A. (1975/1987) The Psychological Birth of the

Human Infant: Symbiosis and individuation. London: Maresfield Library

Figure 6(b): The internalized relationship of mother and baby

When the experiences in Figure 6(a) are internalized in the baby's mind, over time, they are best characterized as intersecting id and superego, producing (cognitive-emotive) ‘ego experiences' in the

(green) dialectical space of interaction, as shown in Figure 6(b).

Those ego experiences, early on, are of emotion arousal, of satisfaction and dissatisfaction; comfort and discomfort; of being served by ‘a good mother’ or being thwarted by ‘a bad mother’.

(Gomez, 1997). The emotions are aroused in the limbic system, but it is my hypothesis that the memories are laid down in the neocortex, as part of the early learning of the individual baby – much of which, in the first year and more, is outside of language – preverbal, nonverbal, memories which some theorists calls ‘the abject’.

Something of this kind of model – of the primordial connection, based on emotional communication, between mother and baby - was what drove the thinking of theorists/practitioners like Winnicott and Bowlby, whose work with children in the UK in the 1950s and

1960s produced a revolution in social policy concerning the treatment of children in schools, hospitals and social welfare contexts. (Bowlby argued that it was the real relationship between mother and child, or child and carer, that determined the psychological state of the child, and not, as had been argued by

Melanie Klein, fantasies in the mind of the child). This new conception of how children and young people were affected by emotional relationships also fed into the campaign against mental asylums, and the development of relationships between individuals

with emotional wellbeing problems and their ‘key workers'. (Gomez,

1997: 5) 31 .

The idea that our earliest experiences are internalized as guiding patterns for future actions and interpretations is now widely agreed.

According to Gerhardt (2004: page 24):

“These unconsciously acquired, non-verbal patterns and expectations have been described by various writers in different ways. Daniel Stern (1985) 32 calls them representations of interactions that have been generalized

(RIGs). John Bowlby called them ‘internal working models’

(1969) 33 . Wilma Bucci called them ‘emotion schemas

(1997) 34 . Robert Clyman calls them ‘procedural memory’

(1991) 35 . Whatever particular theory is subscribed to, all agree that expectations of other people and how they will behave are inscribed in the brain outside conscious awareness, in the period of infancy, and that they underpin our behaviour in relationships throughout life. We are not aware of our own assumptions, but they are there, based on these earliest experiences”.

But let us now return to the statement by Fairbairn to which I referred earlier: Fairbairn rejected Freud's scientific premises, and argued that "...the purpose of life (is) relationship rather than the gratification of instincts", and "he proposed a model of the mind which did away entirely with Freud's biological foundations".

(Gomez, 1997: 3).

It eventually became obvious to me that this is black and white thinking, based on the Aristotelian urge to examine things in terms of either/or propositions. In fact, if you look at my two models in

Figures 5 and 6(a) above, you will see that they contain both the biological (id/neonate) and the social/relational (superego/mother).

31

Gomez, L. (1997) An Introduction to Object Relations. London: Free Association

Books.

32

Stern, D. (1985) The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New York: Basic Books.

33

Bowlby, J. (1969) Attachment. London: Pelican.

34

Bucci, W. (1997) Psychoanalysis and Cognitive Science. New York: Guildford

Press.

35

Clyman, R. (1991) The procedural organization of emotions. In: T. Shapiro and R.

Emde (eds) Affect, Psychoanalytic Perspectives. New York: International

Universities Press.

And it is in the interaction and intersection (or overlapping) of the instinct driven baby/id and the culturally shaped mother/ superego that the dialectical space for the emergence of the ego develops. Furthermore, it is the dialectical, self-constructing nature of that ego-space that makes the very foundations of the individual forever social (and biological)! (We carry internalized, cognitiveemotive, interpretative representations of aspects of mother [and - later - father] as symbolic experiences in our [electro-chemical, physical] heads forever, at non-conscious levels).

4. Internalizing Mother (and later, others)

Melanie Klein had argued that the new baby, over time, internalizes

‘parts' of the mother - e.g. the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ breast - and eventually ends up with a representation of the mother internalized as part of the basis of his/her ego. Fairbairn and others argued against this theory. In my view Fairbairn was wrong, and we are indeed strongly shaped by our earliest relationships. Gomez (1997:

53) supports this idea, when she says: "Klein's concept of the self built around the good object expresses her commitment to the primacy of relationship. The core of the self is the confluence 36 with another, underscoring our inescapably social nature".

Professor Douglas Hofstadter (2007) argues that a human ‘soul' - or essence, identity, consciousness or self - is basically a ‘strange loop' of self-awareness, viewed through categories and concepts.

(Hofstadter is Professor of Cognitive Science at Indiana University, with a longstanding interest in modelling human consciousness.)

We are ‘feedback loops', in his theory, because we perceive our own

‘doings' and evaluate them. And we perceive others perceiving us, and relating to us, and this confirms our sense of ‘existing through experience'. This awareness changes our outputs/actions. Noticing our doings, or awareness of action; and noticing how others

(especially, in the beginning, mother and later father) relate to us, creates the illusion of being ‘the one who notices and who is noticed by others' - as opposed to ‘the brain/mind processes that notice; and the body that is noticed'. (Hofstadter, 2007: 207-208) 37 .

36

‘Confluence' means "the junction of two rivers", according to Soanes, C. (2002)

Paperback Oxford English Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press. And two rivers intermingle when they meet, as do two humans who cohabit for long periods of time.

37 Hofstadter, D. (2007) I am a Strange Loop. New York: Basic Books.

Damasio (2000) 38 argues convincingly that our awareness of our internal body states is the referent for our ‘core consciousness’, or

‘core self’, and Hofstadter (2007) seems to be saying that it is our awareness of being observed, and observing ourselves being observed that makes us a strange loop of self-reflective consciousness, and generates our ‘elaborated self’ or our

‘autobiographical self’.

A newborn baby does not have a ‘self', because it has virtually no concepts or frames through which to capture a sense of its own existence. "What makes a strange loop appear in a brain and not in a video feedback system, then, is an ability - the ability to think - which is in effect, a one syllable word standing for the possession of a sufficiently large repertoire of triggerable symbols": (Hofstadter,

2007: 203). The newborn baby ‘exists', and it may be able to ‘feel' its existence, but it cannot yet ‘think' its existence, as it does not yet have any ability to think. However, babies do have a ‘fantastic

(genetic) repertoire' for developing ‘rich and powerful categorization equipment', in terms of ‘hardware' and ‘software': (Hofstadter,

2007, page 209). And furthermore, our earliest non-verbal emotive states form the very foundation of our later cognitive achievements, which will forever have an emotive dimension. That is the fundamental reality that cognitive science and cognitive psychology have ignored for decades, until very recently.

By about the fourth month of life, the child begins to develop a sense of itself as separate and apart from the mother. (Mahler, et al, 1975/1987). This is the beginning of ‘self consciousness’ or consciousness of the self – which depends upon the presence of an

‘other’ to act as a mirror, to reflect us back to ourselves. According to Armstrong (2003) 39 :

“In self-consciousness, we grasp (more or less accurately) 40 our personality as a whole; we think of ourselves as being a particular kind of person. These ‘perspectival’ and ‘holistic’ aspects of self-consciousness are the mental equivalent of the child looking in a mirror. But in this case the ‘mirror’ is made of other people (initially mother – JB). It is how one appears in the eyes and minds of others that comes back as the

38 Damasio, A.R. (2000) The Feeling of What Happens: body, emotion and the making of consciousness. London: Vintage.

39

Armstrong, J. (2003) Conditions of Love: the philosophy of intimacy. London:

Penguin Books.

40 “More or less accurately” here means “in realistic/defensible interpretation”.

material from which this crucial part of self-consciousness is constructed. So the child comes to feel lovable when it sees that its parents see it as lovable. The parents actions, tone of voice, way of looking, smiling, responding, become the reflective surface in which the child sees itself as lovable. Its own actions, gestures, feelings and words are taken up and given back by the parent. This complex kind of reflection, which transforms what it receives, is a crucial vehicle for the formation of self-consciousness; that is, for the child’s view of itself”. (Pages 57-58).

However, we need to be careful here, because, although selfconsciousness depends upon consciousness, the baby has in fact been non-consciously recording how it was non-verbally mirrored by its mother, probably beginning not much more than a few hours after birth. (Lewis et al. 2001). Thus, before there was a conscious sense of self, there was a non-conscious sense of self. (Damasio,

2000).

Hofstadter (page 210-212, and elsewhere) went on to explore the possibility that more than one ‘strange loop' 41 could exist in one brain. He used various thought experiments, including feedback between two video cameras that are trained on each other's output screens; the story of how he had internalized a version of his own wife's ‘self' over a period of decades; and other illustrations; and produced an interesting argument that, although we each develop our ‘core loop' of self-identity, we also internalize copies of parts of the loops that correspond to the identities of those to whom we are close relationally. He goes on to say:

"We now have a metaphor for two individuals, A and B, each of whom has their own personal identity (i.e., their own private strange loop) - and yet part of the private identity is made out of, and is thus dependent upon, the private identity of the other individual. Furthermore, the more faithful the image of each screen (referring back to the video feedback experiment) on the other one, the more the ‘private' identities of the two loops are intertwined, and the more they start to be fused, blurred, and even, to coin a word, undisentanglable from the other". (Hofstadter, 2007, page 210).

41 At this precise point in this narrative, I am tempted to define a ‘strange loop’ as a spiral of action-reflection (in the eyes/mind of another)-action-reflection (as before)action-reflection- and so on. (Later I will conclude that perhaps a strange loop is of

Action-Experience-Personal.Change-Action-Experience-Personal.Change…)

This is a plausible and fascinating concept: the idea of two entangled lives, or braided lives. I struggled with this concept, and how to clarify it, for a long time before I found a clarification in

Damasio (2000). On pages 19 and 20, in a section titled ‘A search for self’, Damasio writes: “The way into a possible answer for the question on self came only after I began seeing the problem of consciousness in terms of two key players, the organism and the

object, and in terms of the relationships those players hold in the course of their natural interactions. The organism in question - (or the baby in our example: JB) - is that within which consciousness occurs; the object in question is any object that gets to be known in the consciousness process - (which in our example is the mother:

JB). Seen in this perspective, consciousness consists of constructing knowledge about two facts: that the organism is involved in relating to some object, and that the object in the relation causes a change in the organism”. (Damasio, 2000: pages

19-20).

This is how I have modelled that insight:

Figure 6(c): The strange loop of internalize experience

Figure 6(c) shows three successive moments of time – t1, t2 and t3. It also shows an organism whose initial condition is expressed by O +x : or Organism plus an unknown complex of experience (x).

That organism then relates to Object O +x : or (human) Object plus an unknown complex of experience (x). That Object ‘changes’ the

Organism which, at time t2 is now labelled Organism O +1 : or

Organism plus one changing experience. That organism, at time t2 relates to the same Object as before, and in the process the object again changes the organism at time t3 so that now it is labelled

Organism O +2 : or Organism plus two changing experiences. At time t3 this slightly changed organism once again relates to the same object, and again the Object changes the organism, so that it is now labelled… and on and on, iteratively, for as long as the relationship lasts. This interactional process involves internalizing a

‘strange loop’ of organism-relating-change-(modified object)relating-change-(further modified object)-relating-change-etc.

Let me briefly link this back to the earlier ‘mirror model’ presented by Armstrong (2003). Armstrong goes on to say: “We need the interpretative attention of another (person) to help us see ourselves in a more balanced way”. (Page 58). And more precisely, we need feedback from our culture in order to know how to grow into an acceptable member of that culture. And we somehow intuit that we had better change in line with their feedback to us; though sometimes we respond from Adapted/Rebellious child; sometimes from Little Professor; and sometimes from Nurturing or Critical

Parent.

Gerhardt (2004) also describes an aspect of this dialectical interaction: “Emotional life is largely a matter of co-ordinating ourselves with others, through participating in their states of mind and thereby predicting what they will do and say. When we pay close attention to someone else, the same neurons are activated in our own brain; babies who see happy behaviour have activated left frontal brains and babies who witness sad behaviour have activated right frontal brains (Davidson and Fox, 1982) 42 . This enables us to share each other’s experience to a certain extent. We can resonate to each other’s feelings. This enables a process of constant mutual influence, criss-crossing from one person to the other all the time.

Beatrice Beebe, an infant researcher and psychotherapist, has

42

Davidson, R. and Fox, N. (1992) Asymmetrical brain activity discriminates between positive v. negative affective stimuli in human infants. Science, 218: 1235-

1237.

described this as ‘I change you as you unfold and you change me as

I unfold’ (Beebe, 2002) 43 .” (Gerhard, page 31)

This, then, is how I conceive of “the internalization of the mother by the baby”. The baby acts and is reflected by the mother. The baby changes tack in response to this feedback. The baby is developing its own ‘strange loop', but at the same time it is completely entangled in the strange loop that is its mother. At the core of selfidentity is the identity of the mother. Later, bits of the father will also get added.

According to Gerhardt (2004) 44 : “The parent must also help the baby to become aware of his own feelings and this is done by holding up a virtual mirror to the baby, talking in babytalk and emphasising and exaggerating words and gestures so that the baby can realise that this is not mum and dad jut expressing themselves, this is them ‘showing’ me my feelings (Gergely and Watson,

1996) 45 . It is a kind of ‘psychofeedback’ which provides the introduction to a human culture in which we can interpret both our own and others’ feelings and thoughts (Fonagy, 2003) 46 . Parents bring the baby into this more sophisticated emotional world by identifying feelings and labelling them clearly. Usually this teaching happens quite unselfconsciously”. (Page 25). When this is done well, it results in a ‘secure attachment style’, in which the child grows up knowing how to manage their own emotions and those of their friends and, later, lovers.

If the parent is not sufficiently emotionally intelligent to be able to manage their own emotions, they will not do this job very well.

This will often result in the child developing a dysfunctional

‘attachment style’ which will come out in the future in the ways in which they relate to their eventual marriage or co-habitation partners.

43 Beeb, B. (2002) Unpublished talk at Bowlby Memorial Lecture. (But see instead

Beebe, B. and Lachmann, F. (2002) Infant Research and Adult Treatment. Hillsdale,

NJ: Analytic Press.)

44

Gerhardt, S. (2004)

Why Love Matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain.

London: Routledge.

45

Gergely, G. and Watson, J. (1996) The social biofeedback theory of parental affectmirroring. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 77: 1181-1212.

46

Fonagy, P. (2003) The development of psychopathology from infancy to adulthood: the mysterious unfolding of disturbance in time. Infant Mental health journal, 24(3):

212-239.

"At this point", says Hofstadter, "even though we are being guided solely by a very curious technological metaphor (of feedback in sound and video systems), I believe we are drawing slowly closer to an understanding of what genuine human identity is all about. In fact, how could anyone imagine that it would be possible to gain deep insight into the mystery of human identity without eventually running up against some sort of unfamiliar abstract structures (like

Freud's id, ego and super-ego)? ... Although my strange loops are obviously very different from Freud's notions, there is a certain similarity of spirit. Both views of what a self is involve abstract patterns that are extremely remote from the biological substrate they inhabit - so remote, in fact, that the specifics of the substrate would seem mostly irrelevant". (Hofstadter, 2007, pages 210-211).

If we think back to my two intersecting circles in Figures 6(a) and

6(b) above, we see the biological substrate as the id, and the

‘strange loop' of self emergence as the ego. The ego depends upon both the biological substrate (the id) and the cultural superstructure

(the super-ego); and the iterative interaction between them: organism-relating-object-change-(modified organism)-relatingetc….. My personality is inexplicable in terms of a mere expression of the kilogram of slimy grey matter in my skull. But it is equally inexplicable (at overt levels) in terms of the cultural patterns that I inherited from my parents - though I know much of that cultural underpinning supports the hybrid culture that I now carry at higher levels of mind.

Hofstadter continues: "At first I had proposed that a human ‘I' results from the existence of a very special strange loop in a human brain, but now we see that since we mirror many people inside our crania, there will be many loops of different sizes and degrees of complexity, so we have to refine our understanding. Part of the refinement hinges, as I just stated, on the fact that one of these loops in a given brain is privileged - mediated by a perceptual system that feeds directly into that brain". (Page 212). All the other loops influence and control us indirectly, by influence, pressures, demands, prescriptions, codes, rules, rewards and penalties, and so on. Thus, though the mother does not directly control the thought processes of the baby, she does have a very powerful indirect control, as one tennis player indirectly controls the actions of their opponent by the ‘game' that they play. (Hofstadter, pages 212-213). But the mother has much more control than a tennis partner, because "Tennis ... does not give rise to deep interpenetration of souls. But things get more complicated when language enters the show. It is through language most of all that our brains can exert a fair measure of indirect control over the other humans' bodies (or actions) - a phenomenon very familiar not only

to parents and drill sergeants, but also to advertisers, political ‘spin doctors', and whiny, wheedling teen-agers": (Hofstadter, 2008. page 213).

Thus the mother wires up the brain of her baby, initially by handling and managing its body; and later by introducing the baby to her language, her linguistic culture, her rules, and her language-based world. But the baby also significantly wires itself up by the way it relates to, and is changed by, its ‘objects’ – mother, father, siblings, peers, teachers, relatives, neighbours, authors, TV characters, and on and on. But we must not forget that the baby is wired up with emotions, which determine how it feels about what its parents do or don’t do, and when it grows up and becomes a parent, it will be guided mainly by non-conscious cognitive-emotive patterns in how it ‘feels it should’ relate to its own babies. Thus emotion is central to all so-called ‘cognitive processing’.

More generally, as Alan Watts points out, "...the task of education is to make children fit to live in a society by persuading them to learn and accept its codes - the rules and conventions of communication whereby the society holds itself together". (Watts, 1990, page

25) 47 . And one of the rules in most western countries is that we must be brought to think of ourselves as quite separate, and isolated ‘individuals', with no overlaps; while in some eastern cultures, such as Japan, the social norm is to see the collective as primary, and the individual as part of a social collective.

All of this social conditioning goes on in the form of languaging, which interfaces with our emotions and feelings. In fact, language is for a human what water is for a fish: the invisible and unexperienced medium through which it swims. And, as Hofstadter points out: "Language plays a further role ... in this matter of establishing a body as the locus of an identity. Not only does it give us one name per body (‘Tarzan', ‘Jane') but it also gives us personal pronouns (‘me', ‘you') that do just as much as names do to reinforce the notion of a crystal-clear, sharp distinction between souls, associating one watertight soul to each body". (Hofstadter,

2008, page 214).

However, Hofstadter has presented a convincing case that substantial aspects of one person can live on in another person after the first person has died: that we are not as individual as we are persuaded by our culture. He goes on to say that "...no one should

47 Watts, A. (1962/1990) The Way of Zen. London: Arkana/Penguin. Pages 125-127, and 179-192.

have trouble with the idea that ‘the same hopes and dreams' can inhabit two different people's brains, especially when those two people live together for years and have, as a couple, engendered new entities (offspring – children – JB) on which these hopes and dreams are all centred". This was how he had felt about his wife,

Carol, before she died, tragically young. "The sharing of so much, particularly concerning our two children, aligned our souls in some intangible yet visceral manner, and in some dimensions of life turned us into a single unit that acted as a whole, much as a school of fish acts as a single-minded higher-level entity". (Page 224).

Why have I laboured this point so much? Because most people are sceptical about the ‘overlapping of individuals', and it is central to my argument that what is true of Professor Douglas Hofstadter and his wife is also, in its own way, true of every mother-baby dyad.

Two ‘loops' (of self-reflective feedback) come to exist inside each of them, and are carried inside for a lifetime: for better or worse!

Figure 7: The baby internalizes a representation of the overlapping interpenetration of its relations with its mother; and the mother internalizes a representation of her colonization of the baby

5. Koan Training and Model Building

Everywhere I went through the summer of 2009, I carried my pocket notebooks with me, and I found myself scribbling more and

more explorations of the intersecting circles that represent the interpenetration of the mother and baby - which is also the overlapping of the id and the superego - giving rise to the space in which the ego develops. This contradicts Freud's theorizing, in which the ego is present almost from the beginning, but the superego does not develop until much later. On the contrary, the basis of the superego is present from the beginning in the

colonization of the baby by the mother; and the ego develops slowly as the space of dialectical interaction between mother and baby fills up with cumulative, interpretative experiences.

At the same time, I felt the need for a new Zen ‘Koan', or

‘challenge'. Since 1980, I have practiced Zen meditation, which is a process of allowing languaging to die down in the mind, so we can experience reality directly 48 , in its ‘suchness', without evaluating it or commenting upon it: or at least minimizing our evaluations. This practice has been shown to reduce stress, and to permanently change the brain waves of practitioners to more relaxed states. In addition, I had in recent years adopted the Zen process of struggling with daily Koans, which are ‘challenging questions'.

49

(The best know Koan in the west is probably ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping?') The origin of Koan training was the need for

Zen masters to develop a way to test the progress of their students, to see if they had achieved some movement on the road to

‘enlightenment' - or understanding of the nature of reality beyond linguistic labels.

50 I have been using Koan training for three or four years, and enjoy the mental discipline. And now here I was, drawing and redrawing my interlocking circles, and thinking: I must

begin a new Koan. So I went to my Runke (1998) box - (containing the book in the footnote below, plus a deck of cards containing Koan challenges) - removed the book; shuffled the deck of cards; and drew out a Koan card. It said: ‘Who are you?' Perfect.

Every day thereafter, as I left home, I began to ask myself the question: Who am I? Who am I?'; and tried to wear out the linguistic part of my mind which tries to produce intellectual

48

Insofar as that is humanly possible. This is, of course, limited, as we mainly ‘see’ with our experience, and not our eyes.

49

Ruhnke, A. (1998) The Zero Experience - Zen Koans. Dublin: Newleaf / Gill &

Macmillan Ltd.

50 Watts, A. (1962/1990) The Way of Zen. London: Arkana/Penguin. Pages 125-127, and 179-192.

answers, so I can get to the more intuitive part of my mind, which makes creative leaps and connects ideas wordlessly.

However, after a few days I had a realization. I should not be doing this as a Koan. I should be doing it as a human science enquiry; a piece of reasoning from what we already know (from the literature)

about the psychology of human nature and philosophy of mind. So

I began to construct a rational answer to my former Koan:

Who am I?

Perhaps I am just this physical organism.

That would satisfy the most extreme eliminative materialist.

Eliminative materialists are essentially ‘reductionists' who try to reduce all phenomena to their ‘physical essence'. An example would be the view adopted by Francis Crick, the co-creator of the double-helix theory of DNA, who "...concluded ... that ‘the self' is

‘no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules: a pack of neurons".

51 Although there is a grain of truth in this statement, it is as wrongheaded as listening to Mozart's Requiem and pronouncing: "That was nothing more that the squeaking of catgut on catgut; the plinking of wooden hammers on steel wires in a piano; the blowing of air through restricted holes in brass instruments; and so on". Most reasonable observers would reject this interpretation as inadequate to explain what is happening here! What Crick's interpretation eliminates is the whole social/ cultural/ emotional level of reality.

Rita Carter, writing about the conscious ‘I', takes us a step further forward with her view that:

"This essential ‘I' is so fundamental that it is impossible to imagine it away. Does it, though, have any more claim to be ‘real' than the transient, ever-shifting (brain) components that could conceivably be erased by a cerebral accident or catastrophic change in circumstances? I think not. Rather it is a set of concepts - intuitive, unconscious beliefs and ways of interpreting information that are programmed into our brains, partly by our genes and partly by our environment".

52

51

Maddox, B. (2007) Freud's Wizard: the enigma of Ernest Jones. London: John

Murray (Publishers). Page 3.

52 Carter, R. (2002) Consciousness. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Page 213.

Crick's emphasis on ‘a vast assembly of nerve cells' overlooked the

essential environment into which the new human organism always arrives - and from which it is impossible to imagine a human escaping. Even if we grow up and decide to become hermits, and live in isolated caves, we still carry historic social environments in our long-term memories.

Furthermore, D.W. Winnicott attributed primary importance to the environment in children's development 53 . ‘Primary’, of course, does not mean ‘sole’. The child brings something with it, and it participates in a dialectical encounter with mother, father and so on, resulting in a confluence of forces that together shape the new individual's character and personality. To remind yourself of the child's contribution to this process, remember the ‘terrible twos' and the ‘teenage revolt'.

So when I said above, Perhaps I am just this physical organism, I was overlooking the whole social/cultural/emotional level of ‘meness'. The idea that I am ‘just a body' does not account for the whole of me: My thinking; my emotions; and my personal history, and experience of my social and physical environments.

Who am I?

Perhaps I am just this physical organism, with all of its experience

(of self and social environment) stored in memory.

That's better, but it needs refining.

Who am I?

Perhaps I am just this physical organism, with all of its cumulative, interpretative experience of self and social environment, stored in

long term memory.

6. The importance of good and evil

At this point I realized that there was something missing here.

Where does good and evil come from? I had studied morality as part of my doctoral journey, and I now remembered a statement by

53

See also Gerhardt, S. (2004)

Why Love Matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain . London: Routledge. Page 20.

Solzhenitsyn which was quoted in Paul and Elder (2006) 54 . This is what Solzhenitsyn said on the subject of good and evil:

"If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being".

My own experience of life, including my reading and studying activities, supports this proposition in opposition to what I see as a tendency towards the naïve view expressed by Nelson-Jones (2001) to the effect that we all have a ‘core of goodness'. (Pages 392-

393) 55 . (Nelson-Jones' position is quite muddled in that he acknowledges that human behaviour can be positive or negative, but he seems to blame the world, and/or the individual's choices, rather than innate tendencies, for the emergence of what Freud called ‘the bad animal', or ‘wolf', aspect of human behaviour. This naïve view of human nature - which is hard to credit in a post-Nazi world - was also shared by Carl Rogers, the founder of personcentred counselling: (Nelson-Jones, 2001, page 96). On the other hand, the Native American Cherokee people had the concept of a war going on inside each human being. That war is between two wolves: the good wolf and the bad wolf.

56 And the wolf that wins the war is the one that is fed the most!

So, one of the most important developmental challenges for every human being is to learn how to starve our bad wolf, and to feed only our good wolf. The core of the good wolf is love, empathy, charity and a range of other virtues (or what Freud called Eros, or the love instinct; while the core of the bad wolf is anger, rage, resentment, envy, jealousy, meanness, and other vices (which

Freud called Thanatos, or the death urge).

57

These insights led to a modification of my model as follows:

54

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2006) Understanding the Foundations of Ethical Reasoning.

Second Edition. The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

55

Nelson-Jones, R. (2001) Theory and Practice of Counselling and Therapy. Third edition. London: Continuum.

56

Vitale, J. (2006) Life's Missing Instruction Manual: the guidebook you should have been given at birth. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

57 Freud, S. (1995b) Beyond the pleasure principle. In: Gay, P. (ed) The Freud

Reader. London: Vintage Books. Pages 594-595; 618-621.

Figure 8 - The good and bad wolf are inherent in human nature, and in human culture, and the proportions are variable in each individual over time, and from situation to situation

If you want a general insight into the good and bad wolf in all humans consider this: It does seem to be the case that humans find it easier to initiate bad habits than good habits; and easier to terminate good habits than bad habits. In this sense, the bad wolf seems to have an innate advantage over the good wolf. This may be why we have had to develop controlling religions, and legal and moral systems: to constrain the bad wolf.

It seems important at this point to refer back to additional literature on this subject which is available to me, in addition to Paul and

Elder (2006) and Vitale (2006), cited above.

Firstly, in his early formulations of his theory, Freud considered that the ‘it', or neonate (or newborn baby), was primitive, unorganized and illogical.

58 He went on to say: "We approach the id with analogies: we call it a chaos, a cauldron full of seething excitations

58

Storr, A. (2001) Freud: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University

Press. Page 60.

... It is filled with energy reaching it from the instincts, but it has no organization, produces no collective will, but only a striving to bring about the satisfaction of instinctive needs, subject to the observance of the pleasure principle".

59

Later in his career, Freud revised this theory heavily, in order to achieve some degree of scientific respectability, by linking it to putative ‘biological principles'. In Freud (1940 [1938]) 60 , he argues that there are essentially two basic urges in the ‘id' - which is (let us remind ourselves) essentially the physical neonate's, or newborn baby's, essence - and these are love and affection (Eros) and hate and aggression (Thanatos) 61 . These are sometimes referred to as the life urge and the death urge. Unlike Freud, I am not trying to establish credibility with biologists, but rather with moral philosophers and developmental psychologists. I do not consider that biologists have anything much to teach us about the human mind, which is a cultural entity - albeit that it is predicated upon a

biological organism, and is in many respects constrained in its structure and organization by that biological organism.

It may be that all of the innate instincts of the human organism can be subsumed within the urges towards love/affection versus hate/aggression; but I very much doubt it. The instinct to suckle the mother's breast, for example, is found in animals at all levels of complexity. We can see it in domestic cats and dogs. But would we ascribe to the suckling urge of a kitten or puppy the urge of "love and affection"? I think not. These are urges that preceded love and affection, and have to do with survival - but as an outcome and not as a motivation. We can never know anything about the urge that drives babies towards the mother's breast, or that urge that leads to pursuing that suckling to completion. These are unutterable, innate urges that underlie all life forms - the life urge; the pattern of innate intelligence that grows life - of nature

naturing, rather than nature natured.

62

59

Storr (2001), page 61.

60

Freud, S. (1940 [1938]) An outline of psychoanalysis. In: Sigmund Freud (1993)

Historical and Expository Works on Psychoanalysis. The Penguin Freud Library,

Vol.15. London: Penguin Books. Pages 618-621.

61

Freud (1940 [1938]), page 621.

62 Watts, A. (1962/1990) The Way of Zen. London: Arkana/Penguin. Page 32.

We do, however, know that the history of every major culture includes a history of moral education of the young 63 . But why should the young need moral education? Only because, left to their own devices, they would often live their lives from not just hate and aggression - one of Freud's two basic urges - but also from greed and envy and inappropriate lust, larceny of other people's goods, and so on. The basic nature of the neonate - in potential, and normally realized in the toddler and beyond - is to be split between:

(1) The bad urges: and wanting to hate and reject any ‘bad object' - mother, father, etc - who frustrates or displeases them. And wanting justice and fairness, but more for themselves than for others; and imposing injustice and unfairness on others, power permitting 64 . (E.g. school bullies, gang members, etc). And:

(2) The good urges: of wanting to love any ‘good object' - mother, father, etc - who serves them and supports them – and wanting what is best for their nearest and dearest.

This kind of splitting of parents into ‘good objects' and ‘bad objects' is described in the literature produced by Melanie Klein 65 . Klein's theory of ‘splitting' suggests that every baby experiences both love and hate for the mother, and significant others, and also splits those individuals (‘objects') into ‘good objects', when they are seen as supportive, and ‘bad objects', when they are experienced as frustrating or unfulfilling. These good and bad objects have their internal corollaries in the form of the baby's bad, aggressive urges, and their good, loving urges.

We also know from authors like Zimbardo (2007) that all humans have a ‘good and faultless side' and an ‘evil and wicked side'.

66

Zimbardo, it may be recalled, has more than forty years experience of reflecting upon psychological experiments to explore the moral tendencies of humans, including: (a) Milgram's electrocution experiments (1963, 1974) 67 - in which very ordinary people went to

63

Haidt, J. (2006) The Happiness Hypothesis: Putting ancient wisdom and philosophy to the test of modern science. London: William Heinemann. Pages 158-160.

64

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2006) Understanding the Foundations of Ethical

Reasoning. Second Edition. The Foundation for Critical Thinking. Pages 4-7.

65

Klein, described in: Gomez, L. (1997) An Introduction to Object Relations.

London: Free Association Books. Page 34-35; 37-38.

66

Zimbardo, P. (2007) The Lucifer Effect: how good people turn evil. London:

Rider. Page 3.

67

Milgram, S. (1974) Obedience to Authority. New York: Harper and Row.

extraordinary lengths in (apparently) harming others; (b) his own

Stanford Prison Experiment (in Zimbardo et al, 1973) 68 , and (c) his special study of torture carried out by ‘ordinary American troops' at

Abu Ghraib prison, in Baghdad, Iraq. One of Zimbardo's (2007) conclusions is that human morality and immorality are ‘situational'.

That is to say, they have more to do with the environmental pressures upon most of us than to do with fixed, inner states. That does not deny that we have innate moral and immoral emotions and tendencies; nor does it deny that our moral education is very important. It only implies that we can be quickly pressurized, forced, or conditioned, into behaving from our ‘evil side', unless we have very strong commitments to resist those pressures. But our good and bad innate sides, and good and bad socialized sides, are taken for granted in the body of research and commentary reviewed by Zimbardo (2007).

The concept of "innate good and evil" - or the two wolves - can be found in many schools of Buddhist philosophy. For example:

'Concerning the nature of good and evil, Nichiren Daishonin states:

"Good and evil have been inherent in life since time without beginning...The heart of the Lotus school is the doctrine of three thousand realms in a single moment of life, which reveals that both good and evil are inherent even in those at the highest stage of perfect enlightenment. The fundamental nature of enlightenment manifests itself as Brahma and Shakra, whereas the fundamental darkness manifests itself as the devil king of the sixth heaven" (The

Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, p. 1113). The Daishonin explains that all people are endowed with supreme good and evil, as well as all the possible life states in between. We can be either as godly as

"Brahma and Shakra" or as devilish as the "devil king".'

'To see our innate good and evil is to experience the joy of accepting our whole being. As Tillich said, "Joy is the emotional expression of the courageous Yes to one's own true being" (The

Courage to Be, p.14) 69 .

68

Zimbardo, P. G., Banks, W.C., Craig, H. and Jaffe, D. (1973) A Pirandellian prison:

The mind is a formidable jailor. New York Times Magazine, April 8 th

, 38-60.

69 Tillich, P.J. (1952) The Courage to Be . Yale University Press.

Such honest and courageous acceptance of the self also marks the beginning of the essential transformation of our lives and the world around us’.

70

On the other hand, Christianity makes good and evil contingent upon acts of free will; but both possibilities, or tendencies, exist inherently, or innately, for all humans. In Christianity, the Bad Wolf is called Original Sin, or innate sinfulness.

The question of innate good and evil is also dealt with in literature.

For examples: To Kill a Mocking Bird, by Harper Lee; and Lord of

the Flies, by William Golding. And also in Shakespeare: e.g.

Macbeth. Furthermore, Paul Oppenheimer, professor of comparative medieval literature and English at the City University of

New York, has published a detailed study of the concept of evil in literature and films.

71

And in politics, the Holocaust was a major indicator not only of our innate good and evil potentialities, but also our capacity to delude ourselves into thinking we are doing good when we are patently performing acts of ultimate evil. But worse was to come, as first the populations of America and Europe had to wake up to the evils exposed by the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-Vietnam War campaigns; and then the truth about life within the Soviet Union:

(Oppenheimer, 1996; pages 172-173).

Let me finally re-present the model that I presented above:

70

By Shin Yatomi, based in part on Yasashii Kyogaku (Easy Buddhist Study) published by Seikyo Press in 1994. Available online at : http://www.sgiusa.org/memberresources/resources/buddhist_concepts/buddhist_concept32.php.

Accessed: 27th December 2009.

71

Oppenheimer, P. (1996) Evil and the Demonic: A new theory of monstrous behaviour. London: Duckworth.

Figure 9 - The good and bad wolf are inherent in human nature, and in human culture, and the proportions are variable

The only deficiency in this model is that the dividing line between the good and bad sides of both id and superego are shown as fixed.

In fact they are highly variable, depending in particular upon moral education and situational factors: (including both pressures to do evil, and temptations or opportunities to benefit from evil acts). But

I have found it too challenging to develop a way to indicate that variability in this illustration. But that variability should always be born in mind.

7. Now who am I now?

So, back to the question: Who am I?

Perhaps I am just this physical organism, with all of its cumulative, interpretative experiences (of self and social environment), stored

in long term memory...

But how am I modelling "cumulative, interpretative experience"?

Figure 10(a): Experiences are stored in long term memory in a time sequence which is cumulative, and in a form which is interpretative

In Figure 10(a), I try to show that some experiences are more fundamental than others, because they occur earlier. This could just as easily, and perhaps more accurately, be shown as a clustering of experiences, with the oldest at the core, and the newer ones building upon them in ever growing outer layers. And it is pertinent to ask, what does this actually look like in the human brain?

Figure 10(b): The cells in the baby’s brain are gradually interconnected, and those interconnections are what are called ‘cumulative, interpretive experiences’ above. (Borrowed, with acknowledgement, from Taylor,

1999 72 ).

There are three images of neuronal connections in a baby’s brain in

Figure 10(b): at birth, on the left; at 2 years, on the right; and at

15 months, in the middle. What is shown as a space ‘filling up’, metaphorically, in Figure 10(a), is preexisting neurons forming increasing numbers of interconnections.

The baby arrives with some innate emotional templates and temperamental predispositions. Those are then impacted by cultural experience of limbic resonance, and alter by linguistic cultural experiences.