SOCIOLOGY 15

2009

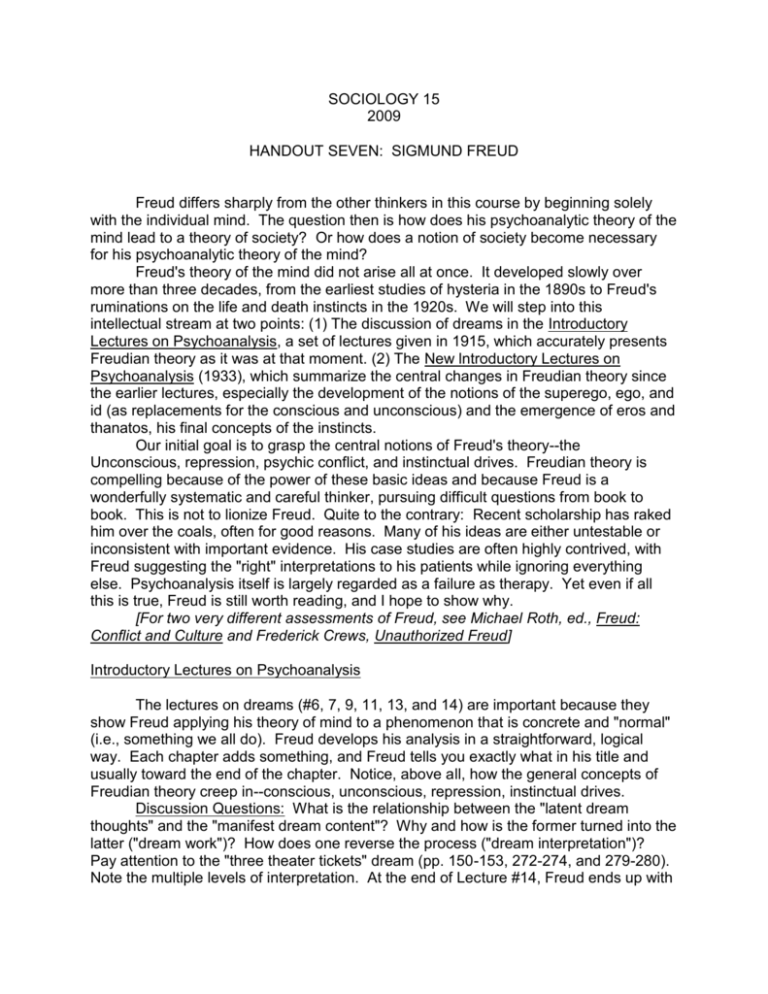

HANDOUT SEVEN: SIGMUND FREUD

Freud differs sharply from the other thinkers in this course by beginning solely

with the individual mind. The question then is how does his psychoanalytic theory of the

mind lead to a theory of society? Or how does a notion of society become necessary

for his psychoanalytic theory of the mind?

Freud's theory of the mind did not arise all at once. It developed slowly over

more than three decades, from the earliest studies of hysteria in the 1890s to Freud's

ruminations on the life and death instincts in the 1920s. We will step into this

intellectual stream at two points: (1) The discussion of dreams in the Introductory

Lectures on Psychoanalysis, a set of lectures given in 1915, which accurately presents

Freudian theory as it was at that moment. (2) The New lntroductory Lectures on

Psychoanalysis (1933), which summarize the central changes in Freudian theory since

the earlier lectures, especially the development of the notions of the superego, ego, and

id (as replacements for the conscious and unconscious) and the emergence of eros and

thanatos, his final concepts of the instincts.

Our initial goal is to grasp the central notions of Freud's theory--the

Unconscious, repression, psychic conflict, and instinctual drives. Freudian theory is

compelling because of the power of these basic ideas and because Freud is a

wonderfully systematic and careful thinker, pursuing difficult questions from book to

book. This is not to lionize Freud. Quite to the contrary: Recent scholarship has raked

him over the coals, often for good reasons. Many of his ideas are either untestable or

inconsistent with important evidence. His case studies are often highly contrived, with

Freud suggesting the "right" interpretations to his patients while ignoring everything

else. Psychoanalysis itself is largely regarded as a failure as therapy. Yet even if all

this is true, Freud is still worth reading, and I hope to show why.

[For two very different assessments of Freud, see Michael Roth, ed., Freud:

Conflict and Culture and Frederick Crews, Unauthorized Freud]

Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

The lectures on dreams (#6, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 14) are important because they

show Freud applying his theory of mind to a phenomenon that is concrete and "normal"

(i.e., something we all do). Freud develops his analysis in a straightforward, logical

way. Each chapter adds something, and Freud tells you exactly what in his title and

usually toward the end of the chapter. Notice, above all, how the general concepts of

Freudian theory creep in--conscious, unconscious, repression, instinctual drives.

Discussion Questions: What is the relationship between the "latent dream

thoughts" and the "manifest dream content"? Why and how is the former turned into the

latter ("dream work")? How does one reverse the process ("dream interpretation")?

Pay attention to the "three theater tickets" dream (pp. 150-153, 272-274, and 279-280).

Note the multiple levels of interpretation. At the end of Lecture #14, Freud ends up with

two distinct kinds of unconscious. How are they different from each other? How does

each figure in dreams?

New lntroductory Lectures

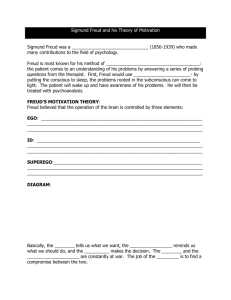

Lectures 31 and 32 discuss how Freud overhauled his theories in a series of

books in the 1920s (e.g., Beyond the Pleasure Principle, The Ego and The Id, The

Problem of Anxiety). Lecture 31 rejects the division of the mind into conscious and

unconscious, opting instead for a division between superego, ego, and id. Lecture 32

replaces the distinction between sexual and ego instincts from Freud’s earlier work with

the distinction between eros and thanatos (life and death instincts).

Discussion Questions: (1) What is the transformation in Freud's instinct theory all

about? He tells us that he once distinguished the sexual and the ego instincts, but now

he rejects that dichotomy. Why? He proposes instead eros and thanatos, the life and

death instincts. How do eros and thanatos differ from the earlier notions of the

instincts? In particular how does the move from sexual instincts to eros change Freud's

understanding of sexuality? (2) Freud rejects his earlier model of the psyche, which

distinguished conscious and unconscious as regions of the mind. What does he mean

when he says (p. 87) that “ego and conscious, repressed and unconscious do not

coincide”? What are the superego, the ego, and the id? How does this new division of

the mind overcome the problems of the older one? (3) At the end of Lecture 31, Freud

describes the goal of psychoanalysis as follows: "Where id was, there ego shall be. It is

a work of culture--not unlike the draining of the Zuider Zee." What does this mean? In

fact, ponder the whole last paragraph of that lecture with regard to what psychoanalysis

is supposed to do and how it does it.

Lecture #33 is Freud's effort to understand gender. That is, it is Freud's answer

to the question of how boys grow up to be men and girls grow up to be women. So,

what does he say? Note that he asserts that up to a certain point the development of

boys and girls is similar: They both have a primary relationship with the mother; they

both move through the first few sexual stages in similar ways.

Discussion Questions: At what point does differentiation occur, psychologically

speaking? The terms penis envy, castration anxiety, and Oedipus Complex are all

pertinent here. I think we will see that Freud is quite ambivalent about the categories

“masculine” and “feminine.”

Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego

In this book, Freud addresses the question of what holds individuals together in

society. Recall that Durkheim argued that self-interest is not enough to hold society

together. Some sense of solidarity, some moral or emotional bond, is necessary.

Weber argued that organized power rarely relies solely on coercion. It seeks

legitimation, acceptance on the part of those being ruled. Freud in effect addresses

both these issues from a psychoanalytic perspective in this book. He wants to know

what psychological processes go into belonging to a group and obeying a leader. He

argues that a libidinal tie of some kind is necessary to group life—i.e., an erotic drive

that has been redirected from its primary objects and desexualized.

Discussion Questions: Freud’s argument is complex, but focus on two things:

First, what are the specific steps through which infantile sexual drives become group

ties? Second, what role do each of these ideas play in Freud’s argument: libido,

identification, narcissism, and the ego ideal?

Future of an Illusion

Future of an Illusion is Freud's most important work on religion and its role in

society. According to Freud, why does society need religion? Could there be a society

without religion? Freud says religion is an "illusion," but that it is not necessarily false.

(p. 39) What does he mean? What does psychoanalysis have to tell us about why

religion has such a powerful hold on people? Finally, Freud says that "religion would

thus be the universal obsessional neurosis of humanity." (P. 55) What does he mean?

Can one call a culture neurotic? What are the implications of doing so?