Poppe 1 Johnathon Poppe Wiesinger Advanced Composition

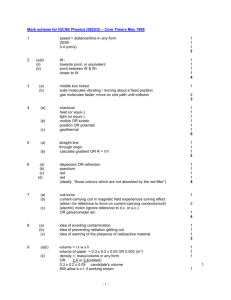

advertisement

Johnathon Poppe Wiesinger Advanced Composition Period 3 30 November 2011 Mercury Is Not Just a Planet The Earth is going to waste. From global warming to the lack of recycling there are many ways humans are ruining their precious home. Additionally, they are unaware of how they are hurting themselves as well. Most people probably know that mercury is hazardous but what they do not know is that the way most people dispose of items containing mercury is dangerous. Fluorescent light bulbs contain mercury and are being thrown away in a way that is harmful to our health. If not recycled properly, mercury can escape into the atmosphere and damage our health. The hazardous waste of mercury can be contained by regulating the recycling of fluorescent light bulbs. Mercury can get into humans’ systems in multiple ways. The most common way is when mercury is released into water. The fish that live in the water are covered in the mercury and then humans consume the fish that were in the water. The mercury is still in the fish when humans eat them so the mercury gets into their system. Proper recycling of fluorescent lights would cut down greatly on the number of people affected by fish with mercury. Methyl mercury affects the nervous system of humans. In infants and young children the most damage can be seen because theirs is not fully developed. With the proper disposal of mercury-filled lights, these awful effects would not be as common. The recycling of fluorescent lights is overall a great positive for Earth, but there are some drawbacks as well. Primarily, correctly disposing of the mercury would improve the overall Poppe 2 health of humans and their environment. Properly recycling the fluorescent lights would destroy the toxic mercury contained in them. If the lights are not recycled, the bulbs could break and expose the mercury vapor into the atmosphere. The methyl mercury would spread and be inhaled by humans, causing illness or death. Obviously, human life is at a premium, but recycling the fluorescent lights could be inconvenient. For instance, normal curbside trash pickup does not have a service to collect mercury products so people must drive to the recycling center to dispose of their fluorescent lights. Gas is expensive and many people do not want to drive their frequently so they choose to just throw away their lights in the normal trash. Also, the gas emitted from driving to the centers would damage the ozone layer, thus ruining our planet in a different way. The quality of human life would improve by recycling fluorescent bulbs because of the cut down on mercury in the open air and water. Less people would get sick due to the harmful effects of the toxic mercury. On the contrary, driving to places where the recycling would happen would be a hassle. If there was an opportunity for mercury-filled fluorescent lights to be picked up along with normal trash, more people would participate in recycling them. Driving all the way to a recycling center could get annoying, but the chance that someone would have to do it often would be fairly rare. The lack of recycling in general is unfair to future generations because the current generation is trashing the planet and not caring that much. The overall feeling is “if it does not affect me why should I care”. If regulations were put on recycling more people would participate. The recycling of fluorescent lights is even more important because of the toxic mercury that is in them. The current generation must start caring for their planet and future generations. Poppe 3 Overall, the regulation of the recycling of fluorescent lights is important because it trims down on the amount of mercury in the environment. While there are some positives regarding the emission and cost of gas as well as it being a hassle, recycling fluorescent lights is important to humans’ health and the environment. More people must properly dispose of mercury if they want to keep themselves and the rest of the world in the best possible shape. Poppe 4 Works Cited "Mercury." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1 Oct. 2010. Web. 30 Nov. 2011.