Course Syllabus in Microsoft Word ()

advertisement

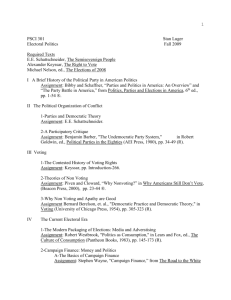

American Political Parties Seminar Prof. Murray: Fall 2006 This course has four principal objectives. First, to introduce graduate students to the prominent analytic and theoretical approaches used to study modern political parties. Second, to examine closely the development and evolution of the American party system, the oldest example of a competitive electoral system in the world. And third, to give students a solid grounding in how the system functions today, in contrast to other democratic party systems across the world. As we work toward the first three goals, we will be covering the extensive literature on American political parties and the party system, which is the final objective of the seminar. Four books are required for the class. These are: Marjorie Hershey, Party Politics in America, 12h ed. Marc Hetherington and William Keefe, Parties, Politics, & Public Policy in America, 10th Ed. Michael Nelson, The Elections of 2004 Gary Jacobson, A Divider, Not a Uniter In addition to these required texts, individual students will be assigned one (or two, depending on class size) of the following books to read and prepare to lead a class discussion on. One week later, a written review of 1500 - 2,000 words will also be required for class distribution. These books are: James Sundquist, Dynamics of the American Party System Robert Michels, Political Parties Maurice Duverger, Political Parties V.O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics and The Responsible Electorate E.E. Schattschneider, both Party Government and The Semi-sovereign People James MacGregor Burns, The Deadlock of Democracy Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes, The American Voter James Q. Wilson, Political Organizations Steven Rosenstone, Roy Behr, Edward H. Lazarus, Third Parties in America Thomas Ferguson, Golden Rule Morris Fiorina, Divided Government and Culture War? The Myth of a Divided America William Riker, The Theory of Political Coalitions Walter Dean Burnham, Critical Elections & the Mainsprings of American Politics John Aldrich, Why Parties? Joseph A. Schlesinger, Ambition and Politics: Political Careers in the U. S. Rebecca B. Morton, Analyzing Elections 1 American political parties are almost as old as the nation, and the United States has the longest history of competitive party politics in the world. This extensive history and the continued importance of American parties makes them favorite objects of scholarly study and analysis. We begin this class by looking at several ways political parties have been examined over the years, starting with traditional approaches – these include historical chronologies, the party reform approach, ideological assessments, case studies, and journalistic analyses. As the discipline of political science matured in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, students of parties began adopting more rigorous methods in their work. They sought to replace case studies with comparative analyses, and to apply analytic approaches from related fields like economics and psychology. Political scientists also adapted chronological analyses by developing Key’s idea of “critical elections” and “partisan realignments.” We will look at several of these approaches, and assess their utility in explaining various aspects of the American party system. Hand-in-hand with these new approaches one notes the availability of new data sources like public opinion surveys, and the extension of techniques such as roll-call voting analysis and content analysis to aspects of the party system. Particular stress is placed on the chronological approach one finds in books like James Sundquist’s Dynamics of the Party System which enable us to trace the development and evolution of the major parties over time. This can be contrasted with the organizational theory approach represented by James Q. Wilson’s Political Organizations, which will also be the subject of a book report and class discussion. One of the most influential approaches follows the work of Anthony Downs’ An Economic Theory of Democracy and William Riker The Theory of Political Coalitions, and is often labeled “rational choice.” If the roots of rational choice lie in the discipline of economics, we see the influence of psychology in the style of analysis utilized in The American Voter and the continuing influence of the “Michigan School.” After this tour of different ways to look at parties, we end up returning to the more empirically grounded work reflected in the Hershey text and the readers. In addition to covering much of the classic and influential literature on political parties in general and American parties in particular, this course strives to ground graduate students in a solid understanding of what is currently happening in American party politics. We rely on the two general texts assigned in this area, plus the Nelson reader on the 2004 election and Gary Jacobson’s new book on President George W. Bush’s leadership style – a style which is highly partisan in the view of the author and most other scholars of the presidency. To further promote an understanding of current partisan politics we will focus close attention on the 2006 elections, which students are expected to monitor using Internet sources as well as print media. We will use this election cycle as a sort of “laboratory” to test some of the ideas discussed in the readings such as the decline versus the resurgence of parties, realignment versus dealignment, and the polarization of parties in a depolarized electorate. 2 Order of Topics/Readings Week One (August 22/24): Introduction to the course. Assignment of book reports. Discussion of the origin and evolution of parties generally. Beginning discussion of traditional approaches to studying American political parties. Read, for Thursday, the Foreword in the Hershey book and Chapter 1 in same. Week Two (August 29 only, because of APSA break). Continue discussing traditional approaches to American parties. First class book report on V.O. Key’s Southern Politics. Students should have read Preface and Chapter 1 in Hetherington. Also read Party Politics on the Internet, pp. 317-324 in the Hershey book. Week Three (Sept 5 and 7). The evolution of the American party system from the Civil War to the late 20th century. Class reports on Michels’ Political Parties and Duverger’s Poltical Parties, Burnham’s Critical Elections and the Mainsprings of American Politics and James Sundquist’s The Dynamics of the Party System. Reports on the Key book distributed to class. Read Chapter 2 in the Hershey book Chapter 2 in Hetherington. Week Four: (Sept 12 and 14). Examining the modern American party system: Party Organization. Reports on Wilson’s Political Organizations and Schlesinger’s Ambition and Politics and Aldrich’s Why Parties? Read Part Two in Hershey. Week Five: (Sept 19 and 21). Parties and Elections in the U.S.. Reports on The American Voter and Schattschneider’s Party Government and The Semi-Sovereign People, Rebecca Morton’s Analyzing Elections, and Key’s The Responsible Electorate. Read Part Three in Hershey and Chapters 3 and 6 in Hetherington. Week Six: (Sept 26 and 28). Continue discussion of parties and elections in U.S.. Reports on Downs’ An Economic Theory of Democracy and Riker’s Theory of Political Coalitions and Rosenstone’s Third Parties in America. Read Part Four in Hershey and Chapter 4 in Hetherington. Week Seven: (October 3 and 5) Discussion of political parties in government. Reports on Burns’ The Deadlock of Democracy, Fiorina’s Divided Government. Read Part Five in Hershey, except Chapter 16, and Chapter 5 in Hetherington. Week Seven: (Oct 10): Midterm Exam (100 points) 10 multiple choice questions (2 pts each), 3 of 5 short essays (10 pts each), and select one of two long essay questions (50 points). Week Eight: (Oct 17 and 19) Resume discussion of party in government, focusing on U.S. Congress. Report on Ferguson’s Golden Rule. Internet assignments for tracking 2006 elections made. Week Nine: (Oct 24 and 26). Analyzing the 2004 election. Report on Fiorina’s Culture War. Read the Nelson book. 3 Week Ten: (Oct 31 and Nov 2) Previewing the 2006 midterm elections. In-class reports on Internet assignments. Week Eleven: (Nov 7 and 9). Reviewing the 2006 results with updates from our Internet assignments. Week Twelve: (Nov. 14 and 16) President George W. Bush as a party leader. Read the Jacobson book. Week Thirteen: Nov. 21: The Parties and the 2008 election cycle. Week Fourteen: Nov. 28 and 30: The Future of the American Party System. Read Chapter 16 in Hershey and Chapter 7 in Hetherington. FINAL EXAM: 150 points. 15 multiple choice questions (2 pts each), 4 of 7 short essays (10 pts each) and 1 of 2 comprehensive essay questions (80 pts) Class Requirements 1. Class meetings will combine lectures with discussion of readings and occasional book reports by students. All students are expected to take part in the informal class discussions. 2. A research paper of approximately 5,000 words (20 pages of text, excluding notes) is required. An outline of the paper requirements follows. The paper counts for 150 points. 3. Each book reports count a maximum of 25 points, as will the Internet assignment for the 2006 election. 4. Attendance will be taken. Unexcused absences count for a loss of 5 points. Written requests for excused absences should be submitted to the instructor. 5. Course grades will be determined as follows on the basis of the total number of possible points: A … 91.5% and above A-… 89.5 – 91.4% B+… 87.0 – 89.4%/ B … 81.5 - 86.9% B- … 79.5 – 81.4% C+ … 77.0 – 79.4% C … 71.5 – 76.9% C- … 69.5 – 71.4% D+ .. 67.0 – 69.4% D … 61.5 – 66.9% D- … 59.5 – 61.4% 4 Prof. Murray/Fall 2006 Outline for Class Term Paper Selecting a Topic First, remember that a good research paper focuses on a single researchable question or issue. If the theme of your paper cannot be summarized a single question, your focus is likely too broad. Second, it is always a good idea to select a subject that interests you, one that you would like to know more about. If you are not curious about the subject, you will likely have trouble producing a paper that interests an outside reader. Third, make sure early in the game that you can get sufficient information to address the central research question you have settled on. There are many great potential papers, but you only have a few weeks to research your subject. Fourth, papers must be on some aspect of American political parties, but I give you wide latitude within this general area. You may, for example, focus on a 19th century question or issue, so long as you do so in an original manner. Suggestions for Approaching the Subject You Select Strong papers utilize a theoretic or analytic framework to provide direction to the research and the resulting paper. We will discuss a number of such approaches in this class. Try to draw on one in organizing your paper. Let me give you an example or two. Lets say you are interested in the fact that Jewish voters are much more supportive of the Democratic Party than the standard SES model predicts (Higher SES = More Republican Voting). Since the SES model does not work with this voter group, your research question is to explain why it does not, and to offer an alternative explanation that is more satisfactory than the SES model. This might lead you to test a “cultural” model of political behavior drawing on the ideas of people like Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba. More specifically, one might posit that Judaism emphasizes different social values (communitarian) than say, American Protestantism (individualistic) and this might account for Jewish support for Democrats because they support policies that promote goals like racial equality thru affirmative action as opposed to Republicans who favor less governmental intervention in this area. One might also look at non-cultural factors that trump SES policy factors (I.e., Democrats are more supportive of Israel). In any case, having defined a hypothesis, you need to figure out some realistic way to test it. To take another case, perhaps you conclude, after some reading, that Jimmy Carter was an ineffective party leader as president. Your paper tries to answer why that was the case. This 5 might lead you to review the models of presidential performance suggested by scholars like Richard Neustadt or James David Barber. Or you might tackle it from a “congressional perspective” that draws on the literature about the changing nature of Congress in the 1970s (Maybe no Democratic president could have managed his party well in this era.) In each instance, you need to clearly define the dependent variable in your paper. What is it you are trying to explain? Jewish partisan voting behavior in presidential and congressional elections? President Carter’s inability to mobilize strong support from Democratic members of Congress? And your need to define how you will measure variance in the dependent variable. (Democratic presidential vote percentage in elections from 1952 to 2004 might be a good one for the first case, or percentage of bills supported by the administration that are passed by Congress in the second). And you need to define the independent variables in your research. Religious selfidentity, SES status, popularity of the president among fellow partisan identifiers, relative legislative experience of presidents, whatever. Timelines 1) Try to settle on a subject, if not a research question, by September 12th for discussion in class. Then at the class a week later (9/14), you should submit a short proposal (100 – 200 words) describing what you propose to do after further reflection. 2) Three weeks later (October 3rd), submit a two page progress report that identifies the dependent and independent variables in your study and how you propose to measure each, and the major sources you are relying on in your research. 3) Progress reports of 200 words or so should be submitted on Thursday, November 16. 4) A final draft of the paper is due Tuesday, December 5. Length, Sources, Citations The paper should be about 5,000 words, but longer papers are fine. This includes up to 500 words in a bibliography or notes. Use common sense in citing sources – acknowledge others’ work, but don’t footnote obvious things. Good papers should strive to use at least 10 sources, or original data you collect and analyze. 6