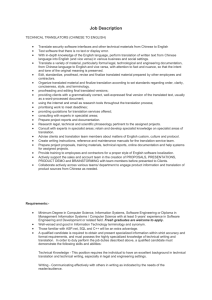

An Introductory Course in Translation

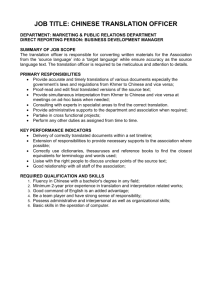

advertisement