McCloskey

advertisement

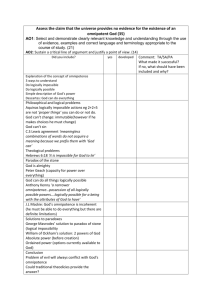

The Nature and Attributes of God --H. J. McCloskey GOD'S ATTRIBUTES AS LITERALLY DESCRIBED A great variety of attributes are ascribed to God. Some are purely negative for example, the attributes of being intangible, invisible, and the like. Others are the so-called pure perfections, life, power, intelligence, wisdom, goodness. Others again are of a kind which, if literally interpreted, would involve limitations, for example being a person, a father, one who loves his creations, and the like. . . . [I]t will be useful here to consider these attributes. . . . Omnipotence On the face of it the literal ascription of unlimited power to God presents few difficulties. We understand by power the ability to sustain or bring about a change, an existence, or the destruction of a thing or a state of affairs; a being has power in that it has the ability to do or to refrain from doing something; we have power in so far as we have the ability to do or to refrain from doing various things. Omnipotence is often explained as the power to do everything and anything that is possible. As G. H. Joyce notes: "Even those who affirm the absolute infinity of God's power, admit that there are things which He cannot do: e.g. that He cannot bring it about that two plus two make five, or that the past should not have happened." And: "Infinite power can realize all things. The objects excluded from omnipotence are so because they are not things at all, but non-things, and hence incapable of realization by reason of their nonentity, not by reason of lack of power in God. It may be well to illustrate each of these two sources of impossibility. Notions which contain contradictory elements are not being. . . . Again, it is no diminution of omnipotence that God cannot do those things which are inconsistent with infinite perfection, and possible only to a finite agent." As these statements bring out, in ascribing power--unlimited power or omnipotence--to God the theist is not involved in understanding "power" in some sense other than that in which we speak of the power a man possesses. Omnipotence, or all-power, is a power greater than all other beings possess and such as not to be limited in any way by the power of lesser beings whose power is dependent on that of the omnipotent being. An omnipotent being can do anything that is possible. It cannot do what is logically impossible for the logically impossible is not something--as Joyce brings out, the logically impossible is a non-thing. An omnipotent being is often spoken of as an infinitely powerful being. This, I suggest, is to introduce a needlessly obscure notion, that of "infinitely," into the account. It is presumably a way of saying that there are an infinite number of possible things that may be done, infinite possibilities for the exercise of power, and that an all-powerful being can do all that is possible. This, I suggest, is unhelpful, as the notion of possibility here is logically subordinate to the notion of unlimited power; the possibilities are all those things an all-powerful being can do. In light of these considerations, it is surprising that any theist should wish to ascribe power, all-power or omnipotence, to God in any but a literal sense. The sense in which God has power, is that in which we are ascribed power. God's power is simply greater and such as to make our power not simply subordinate to but dependent on his power. . . . Most of the paradoxes [involving omnipotence] turn on a confusion between what an allpowerful being may do and must do, or on incompatibilities between omnipotence and other divine perfections. Thus it is suggested that there is a paradox springing from whether the omnipotent being can destroy itself, or whether it can make something indestructible or immovable--instantaneously or over a period of time. . . . I suggest that these are not real paradoxes, that either a logical impossibility is being indicated (e.g. with instantaneous self-destruction creation of an indestructible body), or that God can do what is described, but that if he did he would become a being which was no longer omnipotent. The paradoxes arising from God's omnipotence and his other perfections are most serious. Joyce here observes: "Yet God's inability to do evil places no restriction on Him or His omnipotence." I suggest Joyce is mistaken in respect of omnipotence here. Clearly, an omnipotent being must be able to do what is evil unless by the nature of the case it is logically impossible to do so. . . . It has also been argued that it is mistaken to argue that God, can, by virtue of his omnipotence, do anything at all, for example, something silly. Could an all-powerful being cause a sign to appear in the sky saying "Fortitude beer is best" simply as a result of a whim? I suggest that it must be able to do so. That we do not think God would do so is because we attribute to him other perfections besides omnipotence. . . . Omniscience The concept of omniscience is also one which presents no difficulty in respect of its literal interpretation, but again, it is one which leads to apparent or actual paradoxes. To be all-knowing means exactly that, namely to know all that has been, all that is, and all that will be, all that can be. Omniscience is implied in omnipotence, for a being which lacked knowledge would lack the power to achieve what it wished to achieve. The paradoxes which arise from omniscience chiefly relate to the conjunction of omniscience and other perfections of God, most notably, omnipotence and goodness, and alleged perfections in man, for example, freedom of the will. Goodness Another attribute of God is goodness. God is said to be wholly good in the sense of being wholly morally perfect, willing always what is good, as well as being perfect in all other respects. I suggest that there is no difficulty in understanding the notion of perfect goodness, and that there is no need, nor indeed any possibility of understanding this goodness in a sense other than that which applies to human beings. God is wholly good in the sense in which moral agents in general, according to their natures and contexts and powers, strive to be good. The paradox which arises in respect of God's goodness relates to the question as to whether God is contingently or necessarily good. A being who is contingently good but who may conceivably be evil, may be wholly good in one sense, but lack perfection in another. A being who could not be evil, who is not contingently good but such that we can be certain it will always be good, would appear to be superior in goodness. This is how orthodox Christians see the goodness of God. For them, God cannot commit evil. They explain this in terms of there being no possible motives or reasons for evil for God. The problem or paradox that arises here relates to whether God is thereby necessitated to good, 3 and if so, whether the necessitation to goodness is real goodness. A human person necessitated to act virtuously would typically not be deemed to be virtuous. . .yet an omnipotent being who might be evil, indeed who could be evil, seems less than perfectly good. The Compatibility of the Perfections of God This issue. . . is that of the compatibility of complete power, knowledge, wisdom and goodness. Omnipotence involves the power to do anything that is logically possible; perfect goodness involves the impossibility in some sense of doing what is evil. . . . Wisdom imposes a limitation in that a perfect being cannot do silly things, by virtue of his perfection, wisdom. Omniscience involves further difficulties in respect of omnipotence and goodness. A being cannot be omnipotent in the sense of achieving what it wants to achieve without wisdom and knowledge. Yet if the omnipotent being is necessarily omniscient the problem arises as to how an omnipotent being can be wholly good and yet create, with fore-knowledge and without pre-determination, beings who will be morally evil. 4