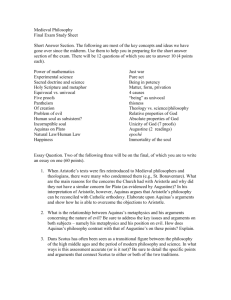

Abstract: In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle distinguished 3 kinds

advertisement

Aristotelian Friendship and Thomistic Charity Craig A. Boyd, Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy & Director of Faith Integration Azusa Pacific University Introduction Interpreters of Thomas Aquinas have often made the claim that the great medievalist’s work is merely a “baptized version of Aristotle.” Theologians in the Augustinian and Reformed traditions often see this as a capitulation to the natural theology that infected scholasticism up through the late middle ages and beyond. A prime example of this criticism in Anders Nygren who contended that the Hellenistic influences in Christianity amounted to a bastardization of genuine Christian theology and ethics.1 Although Aquinas does borrow heavily from Aristotle there are critical differences between the two that go beyond the traditional distinctions made by most Thomists. Etienne Gilson argues that three key differences between the two concerned the resurrection of the soul, divine providence, and the eternality of the world.2 Of course we could point out others; yet, one key place where the two differ concerns the Aquinas’s discussion of charity. A casual interpretation might lead the reader to think that Aquinas merely parrots Aristotle’s account of friendship and then simply applies the concepts to the Christian God. Aquinas does indeed make use of Aristotle’s taxonomy of friendship but there are deep differences that many interpreters have not considered; differences that reach into Aquinas’ “metaphysics of morals,” if I might use the term. 1 Anders Nygren, Agape and Eros, trans. Phillip Watson. (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1952; for a more general criticism of Thomism from reformed perspectives also see Francis Schaeffer, Escape from Reason. (DOweners Grove, IL” Intervarsity Press, 19868) and Helmut Thielicke, Theological Ethics: Foundations, Vol. 1. (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966). 2 Etienne Gilson, The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy. (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1940). 1 In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle distinguishes 3 kinds of friendship: friendship of utility, of pleasure and of worth. Friendships of utility operate on the economic plane while those of pleasure refer to a certain delight one finds among one’s associates. However, friendships of worth are those wherein one friend helps another to the live the best life possible. Aristotle’s treatment of friendship plays a significant role in Aquinas’ treatment of charity; for Aquinas, charity is a “friendship with God.” This kind of friendship corresponds most closely to Aristotle’s friendship of worth but transcends it in two important ways. First, Aquinas’ idea of friendship with God requires a “participation” in God, an idea that Aristotle could not fathom since for him God was entirely transcendent. Second, the idea of loving one’s enemies would be absurd from an Aristotelian perspective since Aristotle’s conception of love requires the good for oneself, one’s family and one’s country. The idea of loving one’s enemy violates Aristotle’s idea of natural political organization. Although Aristotle provides a fairly robust naturalistic explanation of friendship, and at times can account even for radical self-sacrifice on behalf of one’s family or country, he cannot provide an explanation for the kind of enemy love Aquinas discusses. Moreover, it is Aquinas’ understanding of love as a participation in God that enables him to claim that we can even love our enemies. I. Aristotle on Friendship Aristotle’s discussion of friendship in his Nicomachean Ethics stands as the first sustained treatment of the subject in the history of western thought. He claims that “friendship is a virtue, or involves virtue, and besides it is most necessary for life.”3 In all aspects of our lives—since we are by nature social beings—we require friendship. But 3 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin. (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 1985), 1155a. 2 there are at least three varieties of friendship that correspond to the three different goods of “the useful,” “the pleasant” and “the good”; these three kinds of friendship are friendships of utility, friendships of please and friendships of worth. We might call friendships of utility “economic friendships” since they are based upon some sort of mutual interests. In contexts where there is a good deal of economic exchange I may develop friendships with the other, but when my business changes or if I move to another local the friendship dissolves. In this way, Aristotle seems to anticipate evolutionary psychologists who hold that pro-social behavior is necessary for the wellbeing of the individual, and even the group. Friendships of pleasure are closer to genuine friendship since both parties enjoy one another’s company and tend to live together- where those who have friendships of utility do not. Aristotle says that friendships of pleasure are based upon eros and change as our passions change. Again, evolutionary psychologists contend that our sexual desires are often the cause for forming friendships and maintaining them, but if our desires change then the “friendship” also changes. The first two kinds of friendship—those of utility and pleasure—Aristotle says are inferior to friendships of worth because in these kinds of friendship a person uses the other as a means to her own ends. That is, the friendship is an instrumental good not something valued in itself and so Aristotle sees them as incomplete kinds of friendship. Moreover, these friendships are often transient since what is useful and what is pleasurable change according to the tastes and the ends intended by the individual. Friendships of worth are, in contrast, based upon the moral value of the friends and not primarily on the value one person places upon the other’s economic utility, wit, 3 or physical attractiveness. Aristotle says that, “Those who wish goods to their friend for the friend’s own sake are friends most of all; for they have this attitude because of the friend himself.”4 As a result, since the friendship is based upon a desire for the good of the other, this kind of friendship is more enduring than the imperfect kinds of friendship since the desire for the good of the other is not based upon fleeting pleasure or economic advantage. With regard to the general conditions for friendship Aristotle establishes four necessary conditions: 1. one can only have a few friends since friendship with many people is impossible 2. only between persons 3. the friends must practice benevolence 4. the benevolence must be reciprocal Social psychologists have established the fact—one that Aristotle discovered centuries ago—that friendship with many people was impossible. At most, we can have friendships with no more than 200 people, since we cannot maintain any sort of friendship—whether of utility, pleasure, or of worth—with such a large number of individuals. On Aristotle’s view we also cannot have friendship with chocolate ice cream. Our infatuation with the latest American Idol contestant does not qualify as friendship. Nor does our lavishing gifts upon an uncaring, unattainable object of devotion count as love. Friendship can only exist between and among persons since only persons can 4 Ibid., 1156b10. 4 respond to us in intentional ways which precludes the possibility of friendship with inanimate objects. A third characteristic of friendship is that friends not only wish well to their friends they actually practice benevolence; that is, they do good to their friends. In addition to the practice of benevolence we find that the benevolence must be mutual. There is no friendship without reciprocity. Thus, infatuation with an unattainable celebrity is neither love nor friendship; it is merely attraction that is mono-directional. Aristotle adds another qualification; the highest forms of friendship require love (philia) between persons of equal moral worth. As a result, great differences in social status, intellect and moral capacities prevent friendships between husbands and wives, and parents and children from being the highest kinds of friendship. But his raises the question of whether there could be friendship between humans and God? Obviously friendships between humans and God would not be possible for a host of reasons for Aristotle.5 First, since perfect friendships require a relative equality of moral worth (and ontological status), there is no conceivable way for humans to attain the level of God. Second, since God is impersonal for Aristotle, the divine being—who only contemplates the perfection of its own existence—cannot desire the good for the human person. Third, since Aristotle’s God transcends this world in a complete fashion, there is no way for the lives of the human and God to participate in each other—a necessary component of Aristotelian friendship. 5 For Aristotle’s views on God see his Metaphysics, VII. 5 II. Aquinas’ Participation Metaphysics The metaphysical and epistemological structure of Aquinas’ philosophy is a participation metaphysics.6 He says, “[t]o participate is to receive as it were a part; and therefore, when anything receives in a particular manner that which belongs to another in a universal [or total] manner, it is said to participate it.”7 Obviously, humans receive their nature from God and “participate” in God’s creative activity. It can be said that participation is the means by which Aquinas expresses the radical existential dependence of creatures on God. Norris Clarke lists three essential elements in Aquinas’ participation structure: “(1) a source which possesses the perfection in question in a total and unrestricted manner; (2) a participant subject which possesses the same perfection in some partial or restricted way; and (3) which has received this perfection in some way from, or in dependence on, the higher source.”8 The human creature participates in God—the source of all created being—since she derives her very existence from God. God serves as the source of our being and actually is being in a “total and unrestricted manner.” Since humans are made in the imago dei, we participate in the divine reason, the Uncreated Word who is the 6 Craig A. Boyd, “Participation Metaphysics in Aquinas’ Theory of Natural Law,” American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 3 (2005): 431-45. 7 Aquinas, Commentary on the De Hebdomadibus of Boethius, lect. 2. 8 Norris Clarke, “The Meaning of Participation,” Proceedings from the American Catholic Philosophical Association. (1952): 152. 6 expressivum et operativum of the Father. It follows that God, by means of the Verbum Dei, establishes human nature and we participate in the divine nature every time we employ our rational faculties. Thus, all humans participate in the divine being since we are all created by God. The second requirement for participation is that there must be a participant subject which in some partial way possesses the perfection. Humans possess their being directly from God; as John Wippel explains, “In every finite substantial entity there is a participated likeness or similitude of the divine esse, that is, an intrinsic act of being (esse) which is efficiently caused in it by God.”9 All people participate in the divine esse and receive their being from God. As a result of participating in the divine esse all people possess the natural light of reason. Consequently, all humans know that God exists, the primary precepts of natural law, and the specific natures of various natural substances through the natural light of reason. Thus, the human mirror does not reflect God’s image perfectly but only in a restricted manner. The final element of the participation structure is that the participant must have received the perfection from the source in question. In the case of the natural law, the perfection is reason’s capacity to know. That participation enables the agent to act freely and to govern her activities in accordance with reason. The imago Dei for Aquinas bridges the human and the divine. He says, “That the human is made in the image of God … implies that the human agent is intelligent and free to choose and govern itself” (IaIIae, prologue). This intelligence provides the continuity between the human and the 9 John Wippel, The Metaphysical Thought of Thomas Aquinas: From Finite Being to Uncreated Being (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2000), 131. 7 divine. Since humans participate in divine reason by being created in God’s image, they have at least a cognitive capacity to know that need not rely on special revelation or Augustinian divine illumination in order to know certain basic truths about the world. This participation is both an ontological reality as well as an epistemological capacity. By means of participating in being, we participate in the divine being, not in a pantheistic fashion but in a manner which suggests that a radical contingency upon God and God’s creative activity. In an epistemological sense, we participate in God by means of our knowledge through the natural light of reason with which God endows every rational creature. Our minds do not need an Augustinian illumination since we have been endowed in creation with the natural capacity to know and this capacity is bestowed upon us through the divine logos. Both the ontological and epistemological features of Aquinas’ views on participation play an important role in his ethical views, especially as we turn our attention to his consideration of charity as a friendship with God. III. Charity as a Participation in the Divine Being On a casual reading of Aquinas’ Treatise on Charity one might assume that Thomas simply borrows Aristotle’s categories and simply modifies them for his own synthesis of paganism and biblical Christianity. Critics like to argue that in giving too much authority to Aristotle Thomas has perverted the Christian understanding of charity as a theological virtue. Admittedly, Thomas does indeed borrow Aristotle’s categories of friendship, cites Aristotle frequently throughout the treatise, and even contends that “charity is a friendship with God.” However, the nature of our friendship with God is radically different from anything the great Stagirite philosopher could imagine. 8 In the first three articles of the Treatise on Charity Aquinas uses forms of communicatio and paticipatio over 40 times in reference to how humans participate in God. The textual evidence alone is enough to suggest a radical departure from an Aristotelian metaphysics of morals. In the context of the Treatise on Charity, the participation theme signifies both an ontological dimension and an ethical dimension. Ontologically, our very being depends upon God in a radically contingent (and if I may “parasitic”) way. However, it is the ethical dimension—a dimension that depends upon the ontological—that shapes Aquinas’ notion of friendship with God. He says, There is thus a communion that humans have with God in that God communicates his beatitude to us, and our friendship with God is based upon this kind of communion. Concerning this “communion” St. Paul says, “God is faithful by whom you have been called into fellowship with His Son.” But the love which is based upon this communion is charity. It is clear that charity is a kind of friendship of the human person to God.10 Our friendship with God is a communion in the divine nature. He says, that “The divine essence is charity. . . . and the charity by which we formally love our neighbor is a kind of participation in divine charity.”11 But Aquinas is quick to point out that this charity is a gift from God and that we cannot attain it by means of our efforts alone. Charity on this view is God’s invitation to human creatures to participate most fully in the divine life of the Trinity. Although all human creatures participate in the divine life by means of the imago dei and our awareness of the natural law, there is a 10 11 IIaIIae. 23.1. Ibid., 2. 9 “more excellent way” in which we allow God to transform our souls by being united to God. In a fascinating Trinitarian comment on the nature of charity, Aquinas remarks that It is not possible for charity to be in us either naturally nor by means of our capacity to acquire it naturally, but it is by the infusion of the Holy Spirit, who is the Love of the Father and the Son; this participation in us is creaturely charity itself.12 Reminiscent of Jesus’ words in John 15:5, “If you remain in me and I in you you will bear much fruit,” Aquinas goes on to say that charity is both God’s participation in us as well as our participation in God. The intimacy with which charity is described can only arise out of a radically personal encounter with God, one that is simply not possible for Aristotle. There are three ways in which we Thomistic charity differs radically from Aristotelian friendship. These differences are not merely incidental but strike at the very heart of Aquinas’ understanding of charity. Moreover, it is the participation element in Aquinas’ understanding of charity that plays the critical role. By charity we: 1. participate in God 2. love God and neighbor 3. love our enemies As we have seen this first point is an ontological claim that Aristotle could not embrace because Aristotle’s impersonal, celestial God is simply not present to us in the terrestrial world. 12 Ibid., 24,2. 10 Further, it may makes no philosophical sense to say that we could ever love God on Aristotle’s account since God and humans are so ontologically dissimilar. Rather, we might admire, or respect God, but we wouldn’t love God since there is no possibility of the mutuality that permeates all of the Aristotelian species of friendship. Perhaps the third point draws out the distinction between Aristotle and Thomas most clearly; for Aristotle, the virtuous person would have neither the ability nor the desire to love her enemies. By means of our natural capacities we do not possess the ability to love our enemies. Nature has so endowed us with natural affection for kith and kin that we cannot love those who are alien to us. But more than that, virtue—as a second nature—is such that we would have no desire to love our enemies even if we had the capacity. That is, since friendships of worth can only result from two virtuous individuals, love could never result between people of radically different moral qualities since the good person would find the evil person repulsive and the evil person would find the good person equally repulsive. Conclusion In this brief paper I have merely outlined the key differences between an Aristotelian account of friendship and the Thomistic understanding of charity as a theological virtue. While the paper serves a hermeneutical purpose it also points to important contemporary discussions concerning the nature of love in theological context. Questions regarding the nature of God’s “otherness” and the radical differences between the human and the divine seem to collapse under the weight of a metaphysic—like the one Thomas proposes—that appeals to God’s everpresent, omnibenevolent love: a love that empowers all human 11 creatures, even those who choose to reject God and God’s love. As a result, it may be that the metaphysical structure behind a Thomistic account of charity may fit more closely with a process metaphysic than with a more traditional understanding of God as “wholly other.” 12