A Checklist on Where we are in the Doha Negotiations

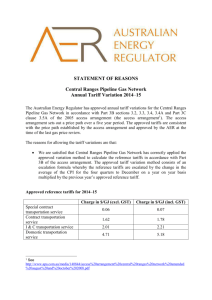

advertisement