Mary_Alt`s_Forum_Pre..

advertisement

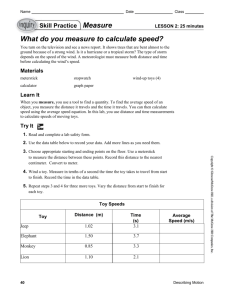

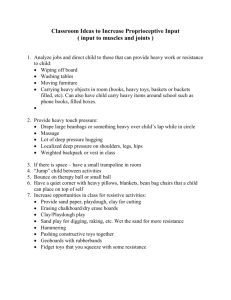

Sex, Gender Role, and Perceptions of Toy Gender Mary Alt & Jeff Aspelmeier Radford University Introduction Philosophers, writers, and scientists have long been interested in the role that sex and gender play in human interactions with the world. Many studies have investigated the difference between the way male and female children play and explore their environment (e.g., Hutt, 1970; McLoyd & Ratner, 1983; Miller, 1987). Also, recent studies have demonstrated sex-related differences in adult exploration as well. Male college students have demonstrated higher levels of curiosity and exploration of novel objects (puzzle toys) compared to female college students (Aspelmeier, in press). The present study tested the hypothesis that males and females may show differences in their ratings of the sex appropriateness and genderedness of toys. Further, we investigate the impact of gender roles (Bem, 1973, 1981) on perceptions of the sex appropriateness and genderedness of toys. It was expected that having more sex appropriate gender roles, would lead to more gendered rating of puzzle toys. Methods Participants Participants consisted of 92 (64 female and 28 male) undergraduate introductory psychology students, ranging in age from 18 to 24 (mean = 18.52). A majority of the sample was Caucasian (89.4%), 5.3% reported African-American ethnicity, and 5.3% failed to report ethnicity. A majority of the sample were Freshmen (75.4%), 19.1% were Sophomores, 3.2% were Juniors, 2.1% were Seniors. Measures Gender Role A measure of gender role classifications was obtained using the Bem Sex Role Inventory (1973). This 60 item measure asks participants rate the descriptiveness of adjectives on a 7 point numerical rating scale (1= very undescriptive of me, 7 = very descriptive of me). Masculine items were averaged to form a masculinity score, where a high score indicates greater masculinity, M = 5.09, s = .5267, and range 2.4. Femininity items were averaged to form a femininity score, where a high score indicates greater femininity, M = 4.97, s = .5800, range 2.9. Classifications were derived using a mean split method (male and female means were calculated separately). A majority of the sample was classified as androgynous (30.9%), 24.5% were undifferentiated, 23.4% were feminine, and 19.1% were classified as masculine. Toy Ratings A measure of the sex appropriateness of toys was obtained using a toy classification measure developed by Miller (1987). Participants are asked to rate each toy on 12 dimensions using a 9 point numerical rating scale. The dimensions associated with “boy” toys include: symbolic play, sociability, competition, handling, constructiveness, aggressiveness, and appropriate for males. The dimensions associated with “girl” toys include: manipulability, creativity, nurturance, attractiveness, and appropriate for females. See Table 1 for Means and standard deviations. Materials The toys included 8 multi-colored cubes and two flattened cylinders filled with liquid, taken from a set of 10 "Bafflers" sold and produced by Pavillion(R) toys. See Figure 1 for examples. Procedures In groups of 8, participants completed the packet of measures (demographic measure, BSRI, and toy rating measure). Each participant rated 4 toys. The order of questionnaire presentation was counterbalanced across participants. Results Preliminary Analyses revealed a significant association between sex, masculinity, and femininity. Males reported more masculinity than female, t(89) = 2.35, p<.03, with means and standard deviations of 5.28 (.5405) and 5.00 (.5046), respectively. Also, females reported more femininity than males, t(89) = 3.55, p<.001, with means of 5.11 (.5720) and 4.67 ( .4854), respectively. The association between sex and androgyny scores was not significant, t(89) = 1.00, p>.05, ns. It was hypothesized that the ratings of male appropriateness and females appropriateness would not significantly differ. A repeated measures t-test was used to test this hypothesis. Contrary to our hypothesis, a significant difference was found between the two ratings, t(91)= 3.74, p<.001. Appropriateness for males ratings were higher than appropriateness for females ratings, with means and standard deviations of 6.39 (1.91) and 5.93 (1.83). To test the hypothesis that males and females would not differ in their ratings of sex appropriateness of the puzzle toys, a series of independent sample t-tests were computed. See Table 2 for means, standard deviations, and t statistics. Females rated the toys as more creative than males, though only marginally significant. Also, females rated the toys as more appropriate for females than males did. To test the hypothesis that adhering to more stereotypical gender roles would result in rating the toys in more sex appropriate ways a series of independent sample t-tests were conducted (See Table 3). Participants with non-traditional gender roles rated the toys as higher in manipulability compared to the participants with traditional roles. Also, Participants with non-traditional gender roles rated the toys as higher in constructiveness compared to participants with traditional gender roles, though this effect was only marginal. Finally the interaction between sex and gender roles was tested for female appropriateness and male appropriateness toy ratings, but was not found to be non-significant, F(3, 83) = 1.14, p>.05, ns, and F(3, 83) = 1.60, p>.05, ns Discussion The present study investigated the role of sex and gender roles in evaluations of a set of puzzle toys used in previous studies. It was expected that having more traditional gender roles would lead to making more gendered ratings of the toys. This hypothesis was not supported. Though, participants with non-traditional gender roles rated the toys as higher in manipulability (a feminine toy characteristic) and constructiveness (a masculine characteristic) compared to participants with more traditional gender roles, no differences were found with respect to ratings of the male appropriateness or female appropriateness. In general, it was found that participants rated the toys as more male appropriate and less female appropriate. This effect seemed to be moderated by the sex of the participants. Females rated the toys as more appropriate for females than males did. Also, females rated the toys as more appropriate for males than males did (though this effect was not significant). Similarly, females rated the toys as more creative than males did (a dimension related to femininity, according to Miller, 1987). Interpretation of the results of the present study is limited by the extreme differences in group size with respect to sex and with respect to the traditional vs. non-traditional gender role groups. Unequal sample size has been found to inflate the Type I error rate (false positives). Conservatively, the results of the present study suggest that the toys used in the present study were not consistently rated as gendered. A study with more equal group sizes may help resolve this issue. References Aspelmeier, Jeffery E. (in press) Love & school: Attachment and exploration dynamic in college. Journal of Personal and Social Relationships. Bem, Sandra. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review. 88(4), 354-364. Bem, Sandra L. (1973). The measurement of Psychological Androgyny. The Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 42(3), 155-162. Bem, Sandra L. (1981). The BSRI and Gender Schema Theory: A reply to Spence and Helmreich. Psychological Review. 88(4), 369-371. Hutt, Corinne, (1970). Curiosity in young children. Science Journal, 6(2), 68-71. McLoyd, Vonnie C., & Ratner, Hilary Horn, (1983). The effects of sex and toy characteristics on exploration in preschool children. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 142, 213-224. Miller, Cynthia L., (1987). Qualitative differences among gender-stereotyped toys: Implications for cognitive and social development in girls and boys. Sex Roles, 16(9-10), 473-487. Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations for Toy Rating Dimensions. M s range Gender Association* Manipulability 4.03 2.82 8 Female Symbolic Play 5.54 1.63 8 Male Creativity 4.98 1.82 8 Female Sociability 3.13 1.65 6.25 Male Competitiveness 4.76 1.83 8 Male Handling 8.23 1.31 7.75 Male Nurturance 1.93 1.31 4.25 Female Constructiveness 2.82 1.78 7 Male Aggression 3.21 1.75 6.75 Male Attractiveness 4.70 1.75 8 Female Male Appropriate 6.39 1.91 6.5 Male Female Appropriate 5.92 1.83 6.75 Female * according to Miller (1987) Table 2 Male and Female Mean Toy Ratings Male Manipulability f 4.45 (2.59) Symbolic Play m 5.34 (1.68) Creativity f 4.48 (1.77) Sociability m 3.45 (1.84) Competitiveness m 5.08 (1.82) Handling m 7.91 (1.22) Nurturance f 2.19 (1.30) Constructiveness m 2.76 (1.63) Aggression m 3.66 (1.85) Attractiveness f 4.60 (1.66) Male Appropriate m 6.00 (1.88) Female Appropriate f 5.40 (1.86) Note. ^ = p<.10. * = p < .05. df = 90. Female 3.88 (2.94) 5.58 (1.59) 5.25 (1.79) 3.02 (1.57) 4.57 (1.77) 8.39 (1.34) 1.80 (1.30) 2.82 (1.86) 3.05 (1.68) 4.77 (1.81) 6.62 (1.88) 6.21 (1.73) t .93 -.67 -1.89^ 1.15 1.27 -1.62 1.34 -.16 1.54 -.45 -1.47 -2.02* Table 3 Sex Appropriate vs. Other Gender Roles Mean Toy Ratings Sex Appropriate Other Gender Role Manipulability f 2.74 4.29 (2.18) (2.89) Symbolic Play m 5.80 5.50 (1.33) (1.60) Creativity f 4.75 5.05 (1.70) (1.84) Sociability m 2.84 3.20 (1.81) (1.63) Competitiveness m 4.45 4.80 (2.08) (1.73) Handling m 8.55 8.17 (.9143) (1.40) Nurturance f 1.92 1.93 (1.49) (1.28) Constructiveness m 2.12 2.94 (1.53) (1.80) Aggression m 3.13 3.26 (1.82) (1.75) Attractiveness f 4.90 4.70 (1.40) (1.84) Male Appropriate m 7.01 6.63 (1.77) (1.89) Female Appropriate f 6.43 5.85 (1.88) (1.78) Note. ^ = p<.10. * = p < .05. t -2.52* df 33.46 .62 89 -.65^ 89 -.81 89 -.73 89 1.11 89 -.052 89 -1.79^ 89 -.28 89 .52 89 1.60 89 1.22 89 Figure 1. Toys