DOC - Europa

advertisement

MEMO/11/917 Brussels, 15 December 2011 Tackling EU cross-border inheritance tax obstacles– Frequently Asked Questions (see also IP/11/1551) What are inheritance taxes? Inheritance tax means all taxes levied upon the death of an individual. Some Member States apply inheritance tax on the heirs, so that the taxable event is the enrichment of the heir. Other Member States apply tax (often called estate tax) on the basis of the assets of the person who has died, in which case the taxable event is the transfer of assets. For the purpose of the measures adopted today, the term inheritance tax is used to mean taxes on both assets and heirs on the occasion of the death of a person. In other words, inheritance tax is used irrespective of the name of the tax, of the manner in which it was levied, whether it is applied at national, regional or local level in the EU and whether it is imposed on the assets of the deceased person or on the heir. Inheritance tax is also defined to include taxes on gifts where these are made in anticipation of later inheritances and where they are taxed under the same or similar provisions as inheritances. What is tax relief? Tax relief means a provision contained in legislation or administrative measures whereby a Member State grants relief for inheritance tax paid in another Member State. This can be done in various ways: by crediting the foreign tax against tax due in that Member State, by exempting the inheritance or parts of it from taxation in that Member State in recognition of the foreign tax paid, or by refraining from the imposition of inheritance tax. Which are the most common cross-border inheritance tax problems? EU citizens and businesses can potentially face two types of inheritance tax problems in cross-border situations. First, there is the risk of taxation of a single inheritance by several Member States with no relief or only partial relief for the double taxation. Second, they may be exposed to tax discrimination. What measure is the Commission proposing to resolve double taxation? The Commission Recommendation suggests how Member States could improve their national double inheritance tax relief provisions. The aim is to provide comprehensive relief for double or multiple taxation. Because Member States have few bilateral treaties to eliminate double taxation of inheritances and seem unlikely to conclude more such treaties in the near future, the Recommendation focuses instead on encouraging Member States to apply their national measures to relieve double taxation of inheritances more broadly and flexibly. The Recommendation suggests an order of taxing rights and relief for previous taxation in cases where several Member States have taxing rights over the same inheritance. In addition, the Recommendation suggests solutions to cases where an heir or a deceased has "personal links" to more than one Member State (e.g. resident in one of the States and domiciled in or a national of another). Member States are invited to introduce the solutions suggested either in national legislation or by way of administrative measures which may entail adopting a more flexible interpretation of existing provisions. What measure discrimination? is the Commission proposing to resolve Discrimination is prohibited under the principles of the EU Treaty, and the Court of Justice of the European Union (the Court) has already found aspects of Member States' inheritance tax laws discriminatory in eight out of the ten cases it examined since 2003. However, there may be many cases of discrimination which have not reached the Court, in particular because court cases may involve high costs for taxpayers. That is why the Commission services have today published a set of principles for non-discriminatory inheritance taxation based on EU case law which explain and illustrate the operation of the fundamental freedoms. These should provide guidance to Member States in bringing their inheritance tax provisions into line with EU law. They should also make EU citizens more aware of the rules which Member States must respect when taxing cross-border inheritances. What are the problems of double taxation of inheritances and why do they occur? When the deceased, the heir and the assets to be inherited are all located in different countries, all the countries involved may claim a right to apply inheritance tax. In such situations there is a risk that the tax bill of the heir may be enormous because there is no EU law and few bilateral tax treaties between Member States that require tax paid in one country to be set off against tax due in another. Although most Member States provide some double taxation relief under national law, these national provisions usually have a limited scope. For example, a country that applies an inheritance tax to heirs may not allow credit for an income tax, estate duty or stamp duty that another country applies to the same inheritance. The Commission believes that if EU citizens are to benefit from their right to move around freely within the Internal Market this double taxation should not occur. It recently adopted a Communication on Double Taxation (see IP/11/1337) to highlight where the main double taxation problems lie within the EU and outline concrete measures that the Commission will take to address them. The present Recommendation is one of those initiatives. What are the problems of discrimination in the field of inheritances and why do they occur? Some Member States' national tax rules may apply a different treatment to crossborder inheritances compared with local inheritances. For example, they may apply a higher rate of inheritance tax where the assets, deceased persons and/or heirs are/were based in other countries than they would apply in purely domestic situations (i.e. where the inheritance, heir and the deceased are all located in the territory of the taxing Member State). 2 This is because many Member States’ inheritance tax rules were not designed with foreign inheritances in mind whereas the reality is that citizens now change their countries of residence more frequently and purchase and invest abroad. For instance, cross-border real estate ownership in the EU has increased by up to 50% between 2002 and 2010. Member States which discriminate concerning the residence of the deceased or the heir, or the location of the assets may breach EU rules and can be taken to Court. However, many EU citizens may not be aware of the rules Member States must respect when taxing inheritances received across borders. It is for them in particular that the Commission services have today published principles for nondiscriminatory inheritance tax systems. Do all countries apply inheritance taxes? Not as such. Eighteen Member States levy specific taxes upon death. Nine Member States (Austria, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Sweden) do not do so but may tax inheritances under other headings such as income tax. Those Member States applying inheritance taxes have widely differing rules. They differ regarding whether they tax the assets or the heir or both i.e. whether they tax on the basis of a personal link of the heir or the deceased, or both, to those Member States. Furthermore, they may treat as a personal link the residence, domicile or nationality of the deceased or of the heir and some Member States use more than one of these factors. The meaning of these terms may also differ from one Member State to the other. In addition, most of the 18 Member States apply inheritance tax to assets located in their jurisdictions even if neither the deceased nor the heir has a personal link with the jurisdiction in question. What is the scale of the problem of cross-border inheritances? In 2010 more than 12 million EU citizens lived in a Member State other than their home country, an increase of 3 million compared to 2005. The trend in crossborder ownership of assets is also growing massively. It is therefore likely that more assets may be inherited across borders than in the past and that this trend will continue in the future, with consequent tax problems. Even very conservative estimates point at a current range of 290,000 to 360,000 potential cross-border inheritance cases per year. There is already some evidence of an increase in cross-border inheritance tax problems in recent years. The Commission has received many more complaints and enquiries from EU citizens in this area in the last decade than ever before. Furthermore, the Court, which never dealt with an inheritance tax case before 2003, has, since then, had to make decisions in ten such cases. With a steadily increasing tendency in migration and cross-border ownership of assets within the EU, there are clear and robust indications that tax problems will increase in magnitude over the coming years if no action is taken now. While at individual level citizens could suffer very high overall taxation if they are taxed by two or more countries, revenues from domestic and cross-border inheritances taxes account for a very small share - less than 0.5% - of total tax revenues in EU Member States. Cross-border cases alone must account for far less than that figure. 3 Will these proposals concern Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)? The solutions proposed would also be applicable and beneficial to individuals who inherit SMEs across borders. SME organisations frequently point to the particularly damaging effects of inheritance taxes on small businesses, and say that the application of double taxation would aggravate the problems further. In addition, among the set of principles published today there are some which provide guidance for the non-discriminatory inheritance tax treatment of businesses such as SMEs. Is the Commission in making this proposal looking after “fat cats”? There are millions of people who are struggling to make ends meet for whom double taxation of inheritances is the least of their worries. The lack of comprehensive solutions in eliminating double taxation could actually affect ordinary people most as the wealthy are more likely to have tax advisers to help with tax planning. Wealthier citizens may take account of the risk of double taxation in planning their international successions but the same may not be true of less wealthy individuals who may only realise the extent of the problems when they are actually facing cross-border inheritance tax bills. What is the EU competence in the area of inheritance taxation? Member States are free to design their rules in the area of inheritance tax as they wish. However, in the first place, they must apply those rules in accordance with EU rules. This means that they cannot discriminate on the basis of nationality or apply unjustified restrictions to the exercise of the freedoms guaranteed by EU rules. In the second place, the Commission is responsible for addressing problems which affect the operation of the internal market and double taxation and discrimination in the field of cross-border inheritances are examples of such problems. In fact, the snapshot of citizens' and businesses' concerns in the Internal Market published in August this year (see IP/11/1074) confirmed that inheritance tax issues feature among the 20 top problems faced by citizens and businesses when active across borders. The Commission’s Recommendation does not propose that Member States abolish or harmonise their inheritance tax rules. It only suggests how Member States could ensure that there is a system of comprehensive double taxation relief within the EU. This would only require small changes to their existing systems of double inheritance tax relief. The Recommendation is proportionate and fully respectful of Member States’ sovereignty in inheritance tax matters. As far as discrimination is concerned, the Commission, as guardian of the proper application of the EU Treaties, has a responsibility to examine any problems that arise and ensure that they are eliminated. Member States are obliged in any event to take action to bring their systems into line with decisions of the Court. 4 How are the measures that the Commission adopted today linked to the proposal for a Regulation on the jurisdiction and applicable law in matters of cross-border successions (see IP/09/1508) which is currently under discussion by the Council and the Parliament? The proposed Regulation is designed to clarify which Member State’s civil law should govern a cross-border inheritance. However, it does not deal with taxation issues. The Recommendation adopted today will not, therefore, have any impact on the outcome of the future Regulation but could certainly complement it by proposing appropriate solutions to the relevant cross-border tax problems. The Commission just recently adopted a Communication (see IP/11/1337) on the possible ways to address double taxation of both individual and corporate taxpayers within the EU, with a view to presenting solutions in 2012. Is there any need for a separate initiative to tackle double taxation of cross-border inheritances? Yes. Taxation of inheritances presents problems which have no exact counterpart in income/capital taxation. The way Member States establish personal links in the case of income/ capital taxes, with a view to exercising taxation rights on a person, are more or less uniform and follow international practice. However, the personal links in the area of inheritance taxation vary considerably (see above) so they give rise to a much bigger number of situations where inheritances could be subjected to double or even multiple taxation. Moreover, it seems that rules in the inheritance tax area vary much more from one Member State to another than in the income tax area. In addition, while the network of bilateral income tax treaties is almost complete, there are few bilateral conventions between Member States in the inheritance tax area and the OECD model convention on which they are based has not been updated since 1982. The Communication on Double Taxation recognised that existing and planned instruments to relieve double taxation of income and capital cannot efficiently tackle cross-border inheritance tax issues and that separate solutions would be required in that tax field. Will this initiative harmonise Member States' inheritance tax rules? No. The Commission believes that there is no need to harmonise Member States’ inheritance tax rules. All that is necessary is for Member States to make their very disparate national tax rules interact more coherently with each other so as to eliminate double taxation in a comprehensive way. That is the purpose of the Recommendation adopted today. Why does the Commission not table a legislative proposal? At this stage the Commission believes that its Recommendation is the most effective, efficient, speedy and proportionate means of tackling the double taxation problems. Nevertheless, the Commission reserves its right to present a legislative proposal in the future, if deemed appropriate. 5 What are the next steps? The Commission will enter into discussions with Member States to encourage them to change their national laws along the lines of the Recommendation and published principles as soon as possible. It will also monitor how the situation evolves, and publish a report in three years time. On that basis the Commission will take appropriate follow-up steps if necessary. Meanwhile, the Commission, as the guardian of the Treaties, continues to take the necessary steps to act against discriminatory features of Member States taxation rules. How many double inheritance tax treaties exist between Member States? There are only 33 bilateral inheritance tax treaties between Member States out of a possible total of 351. Could you give some examples of cross-border inheritance tax problems? NOTE: The examples below are based on our interpretation of the most recent and available information on the laws and practices in Member States. The legislation and practices are subject to change which could affect these examples. 1) Two Finnish sisters, one living in Finland and the other living in Sweden, inherited an apartment in Belgium from their uncle who lived in Finland at the time of his death. Belgium, as the country of location of the apartment, applied inheritance tax amounting to nearly 60% of the value of the apartment. Additionally, they had to pay inheritance tax of around 13% in Finland because their uncle was a Finnish resident at the time of his death. The sister residing in Finland could offset the tax paid in Belgium against the 13% due in Finland, but the sister residing inSweden could not, because under Finnish legislation the tax relief is only available to heirs resident in Finland. She therefore paid 73% tax on her share of the apartment (fortunately, as Sweden does not tax inheritances, she did not have to pay any tax there). 2) A Polish resident inherited assets from an unrelated person in France and paid a French tax of 60% of the value of the assets because of the fact the deceased lived in France. As the Polish heir lives in Poland, she also had to pay inheritance tax in Poland on the same assets. She hoped that the bilateral tax treaty between France and Poland could eliminate the double taxation but learnt that this bilateral tax treaty does not cover inheritance taxes. Therefore she was only allowed a small amount of tax relief under Polish national law in respect of the tax paid in France with the result that the overall effective tax rate applied to her inheritance, as a result of the tax applied in the two countries, amounted to around 65%. 3) A Dutch citizen working in France inherited a property in France from his deceased life partner who was also a Dutch citizen and who had lived in France for the previous 6 years. Their relationship had not been formalised. The Dutch heir had to pay French inheritance tax in view of his residence in France and of the fact that the property concerned was located in France. However, he also had to pay inheritance tax in the Netherlands because his deceased life partner was deemed to have been resident in that State. 6 For the purposes of inheritance tax, Dutch nationals are deemed to have resided within the national territory for 10 years following the date they leave the Netherlands to live abroad. The tax applied by France amounted to nearly 60% of the net assets. The effective tax rate applied by the Netherlands would normally amount to more than 30%.However, under the legislation applied by the Netherlands, foreign taxes are deductible as a liability on the inheritance received and, therefore, the tax applied by France led to a reduction of the tax in the Netherlands to roughly 12.5% and thus to an overall tax rate of 72,5%. Double taxation was not fully eliminated and the total tax due on the property concerned was higher than it would have been had the inheritance been confined to any one of the two Member States concerned. 4) A resident of Slovenia inherited a cottage in Spain from her uncle who lived in Belgium. The Slovenian heir had to pay Slovenian, Belgian and Spanish taxes. The Slovenian tax of around 14% was due because the heir is resident in Slovenia. Belgian tax of 59% was due because her uncle was resident in Belgium. 7.5 % tax was due in Spain because of the location of the real estate in Spain. Belgium allowed credit against Belgian tax for the 7.5% Spanish tax, because it allows credit for tax on real estate in the country where the estate is located. However, Belgium did not allow credit for the tax paid in Slovenia and nor did Slovenia allow credit for the tax paid either in Spain or Belgium. Therefore, the overall taxation with relief amounted to about 73% of the cottage value (7.5% in Spain, 59% in Belgium less credit for the the Spanish tax, and 14% in Slovenia). 5) A Hungarian national living in Belgium inherited assets in a Hungarian investment fund and in Hungarian banks from her uncle who lived and died in Belgium. Because the property was located in Hungary she paid approximately 30% inheritance tax in Hungary. She also has to pay inheritance tax in Belgium amounting to nearly 60% of the assets value because her uncle had been a Belgian resident for more than 5 years prior to his death. Belgium grants a relief for foreign inheritance tax, but only for taxes levied on foreign real estate; in the case of financial assets no relief is applicable. Hungary does not allow credit for tax paid elsewhere on movable property located in Hungary. The heir's total tax bill therefore amounts to nearly 90%.The heir faces great financial difficulty because if she sells the investment fund now rather than at a maturity date in future, she will be penalised and nevertheless she has to pay the tax now, so she has to take out a loan to settle the tax bill. 6) A resident of Denmark inherited a summer house in Portugal and a long term savings account in Denmark from her uncle who was domiciled in Denmark. The Danish heir had to pay Portuguese stamp duty amounting to 10% of the net value of the summer house because Portuguese law subjects transfers on the occasion of death to transfer tax. Moreover, she had to pay Danish inheritance tax on both the Danish savings and the Portuguese summer house because under Danish rules, worldwide assets of the deceased are subject to inheritance tax in the hands of Danish resident heirs, at a rate in her case of effectively 34%. The Portuguese stamp duty could not be credited against Danish inheritance tax because the Portuguese tax is a transfer tax and not strictly speaking inheritance tax. The total inheritance tax she must pay on the Portuguese house is, therefore, 44%. 7 7) A Belgian citizen living in Spain inherits a house in Belgium and savings in a Hungarian investment funds from his uncle who was a resident in Belgium. Belgium applies its inheritance tax to both the Belgian real estate and the investment in the Hungarian funds because the deceased was a resident in Belgium and the real property is located there. Spain imposes its inheritance tax on the heir since the heir is a resident of Spain. Hungary for its part imposes a tax on the investment assets since they are located in Hungary. Assuming that the values of the real estate are average and the value of the investments is quite high, Belgium would apply its inheritance tax to all the assets at a level of around 68% and Spain would apply its inheritance tax to on all the assets at approximately 20%. Hungary would tax the investment at a level of around 36%. Spain would probably allow a credit for Hungarian and Belgian tax but only up to the amount of the Spanish tax due. Belgium would not allow a tax credit for Spanish tax or for Hungarian tax because Belgium only gives credit for tax on real estate situated abroad. Hungary would not allow foreign tax relief on Hungarian liquid assets. Therefore, overall taxation might amount to over 100% - 68% plus 36% on the inheritance. 8 9

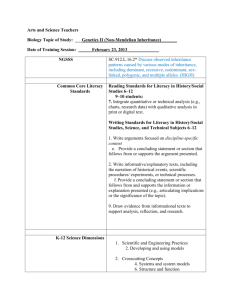

![[11.1,11.2,11.3] COMPLEX INHERITANCE and HUMAN HEREDITY](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006715925_1-acaa49140d3a16b1dba9cf6c1a80e789-300x300.png)