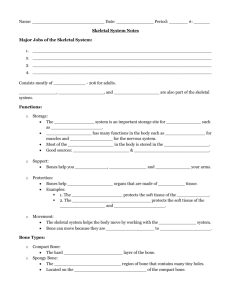

Animal bone

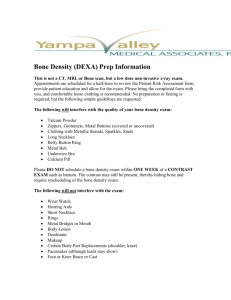

advertisement

What do archaeological artefacts tell us? Archaeological artefacts are the objects or parts of objects left behind by people in the past. They can tell us about manufacturing techniques, trade and exchange, eating habits, clothing, display, spiritual beliefs and much more. They can be dated and help to date an archaeological site. However, unlike written documents, which are relatively easy to read, artefacts need a lot of interpretation to make them speak. You can identify artefacts by working out the answers to a few simple questions: What colour is the artefact? How heavy is the artefact? What shape is the artefact? What is the artefact made out of? Is there any kind of decoration? By comparing the answers to these questions against artefacts that have already been identified, archaeologists can work out what the artefact was and maybe what it was used for. Compare your artefacts against the illustrated glossary below to work out what your objects are. The scale in each picture is 10cm long. Pottery The lip of a pot is called the rim, the sides are called the walls and the bottom is the base. Glaze is a shiny surface that is created by covering the surface of the pot with a substance based on glass. The fabric of the pot is what you can see on the broken edge. This rim sherd is reddy brown, has a glaze on the inside and has a grey fabric sandwiched between outer layers of red fabric. The glaze makes the inside surface very smooth and slippery. This probably dates to the medieval or post-medieval period, because of the glaze. Having the glaze just on the inside suggests that this vessel was intended to carry liquid. This sherd of pottery is from the body of a pot. It has a black surface and a black fabric. It is not very attractive, is very rough to touch and may date to the Iron Age or the Saxon period. This base, seen from both the inside and the outside, is in a pottery style called Samian ware. This is Roman in date. Samian ware is identified from the red burnish on the surface. This is created by dipping the pot in clay mixed with water, which created a hard surface when fired in a pottery kiln. It gives it a smooth surface, unless it is eroded away like the one above. This Samian ware dish has a foot ring, which is the circular bottom bit it stands on. The fabric is grey sandwiched by red. Other fired clay objects This is a chunk of brick from Penn. Bricks were sometimes made and used in the medieval period but were not used with any regularity until the Tudor and later periods. Bricks started out fairly thin, almost like tiles, and gradually got thicker through the following centuries. This brick looks quite thick, so is probably of an eighteenth or nineteenth century date. This is a peg tile. You can see the holes where the pegs would have gone to attach the tile to a roof. This tile is much thinner than the brick above, as it couldn't be too heavy or the roof would collapse. Peg tiles were used as roof coverings from the medieval period onwards. It is often quite difficult to date them. This is a floor tile. It is heavier than the roof tile above and therefore would be too heavy for roof. Tiles would usually only be used on the ground floor as they were so heavy. This floor tile is also glazed. Roof tiles did not tend to be glazed, as few people would see them, whereas everyone saw floor tiles so they had to look nice. These clay pipe fragments can look quite like bone. However, the hollow stem is too thin and too regular to be a bone, and the bowl (centre) often has signs of burning inside and decoration on the outside. Clay pipes are usually made of a white clay, and the stem is very smooth to the touch, whereas bones are rougher. Also, the hole running through the stem is far too small to be a bone. Opus signinum is a type of Roman floor material. It is often light pink in colour (above right). It covers a whole floor in one large surface, rather than being a series of tiles fitted together. Opus signinum was an alternative to a mosaic floor and covered rooms that did not need mosaics, such as servant's quarters. This blue and white ware is quite modern. These pieces date from the nineteenth and twentieth century. You often find a lot of this in your gardens as people used to throw their rubbish out into the back yard before there were proper rubbish collections. Animal bone This bone is part of a long bone in an animal's leg. It is close to the joint, the bone is starting to curve up to meet the joint in the picture on the left. The reason you can tell it is an animal bone and not human is because the bone is very thick and only has a small hole running through it, as you can see in the picture on the right. You can see the bone is not white like the clay pipe, is quite rough and is not a regular cylinder shape. This small bone is probably from an animal's foot. It is a knucklebone but is much too big to be a human hand or toe bone. Human hand and toe bones tend to be long and slender and any short pieces are much smaller than this. Once again you can see the walls of the bone are very thick, with only a thin hollow running down the middle. The bone is rough and irregular in shape. You can see the joint of this long bone. The straight cut in the centre of the bone suggests it was butchered for meat. Flint Flint is a type of stone. Before people learned how to make metal, stone was used for things like tools and weapons. These artefacts date to the Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age, from between 500,000 to 10,000 years ago. Flint artefacts like this are usually very distinctive and have a defined flaked cutting edge. These are known as handaxes though it is likely that they were hafted to a handle as well as being used in the hand. It is generally thought that these artefacts were used as weapons, for chopping down trees and as cutting tools. These flint tools date to the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, from about 4000 to 2200 BC. Even though they are both of similar date the flints on the left have a surface patina that has turned them white, while the flint on the left is still black. The patina was probably due to being buried in chalky soil on Whiteleaf Hill, whereas the flint on the right was found in Haddenham, which is on clay. The flint from Haddenham is called a knife and it is thought it was used for cutting meat and vegetable fibres. It may have been useful as a skinning tool as well. The flints from Whiteleaf include an arrowhead (central flint), a scraper for scraping skins (on the right) and three smaller flints that may have been fitted into a composite artefact. Coins These gold coins date to the Late Iron Age. Coinage was virtually unknown in Britain before around 100 BC. These coins were based on coins of Phillip of Macedon from Greece that had made their way around Europe. As time went on coins grew less and less like the Macedonian coins. It is thought that these coins weren't used as currency in the same way we do. They may have been given as payment to Britons who went to fight in Gaul against Julius Caesar. Coins like these are often found together in hoards, as if people had collected them and then buried them for safekeeping. Shell Oyster shells are often found on archaeological sites. Unlike today when oysters are expensive and are not eaten by many people, in prehistoric, Roman and medieval times, oysters were a cheap and abundant food source. The two white oysters in the picture come from a Roman villa in Foscott whereas the grey example is much older and has become fossilised. They are still recognisable even if they have turned grey as they have a layered texture on the outside (see above right), and they have the distinctive shape. When alive an oyster has two shells held together protecting it from predators. Slag Slag is the waste product of metal-working. Most metals are found as ores, there are not many that occur as pure metals naturally. Ores are compounds of metal and many different elements. When heated, the metal is melted from the rest of the ore, which fuses together into slag. As a consequence, slag is very rough, has a very irregular shape and can be all different colours. Glass These pieces of glass are a very deep green and have thick walls. They are not very see through and are curved. This type of glass was produced in the post-medieval period for bottles. Other types of glass may be more translucent, thin, flat and stained with bright colours, which may be window glass. Roman glass was often recycled, which caused the glass to go from white to a pale green. Care should be taken when handling glass as the edges stay sharp. Fossils These fossilised oysters were found in Aylesbury. When dinosaurs roamed the earth, Aylesbury Vale was underwater. It is common to find fossils of marine animals in this area. Fossils look like they are made of stone but at one time were living things. The way you can tell they are not merely stones is that they display a pattern or shape of a living thing.