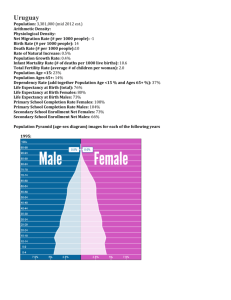

Word - Unicef

advertisement