Research Summary

advertisement

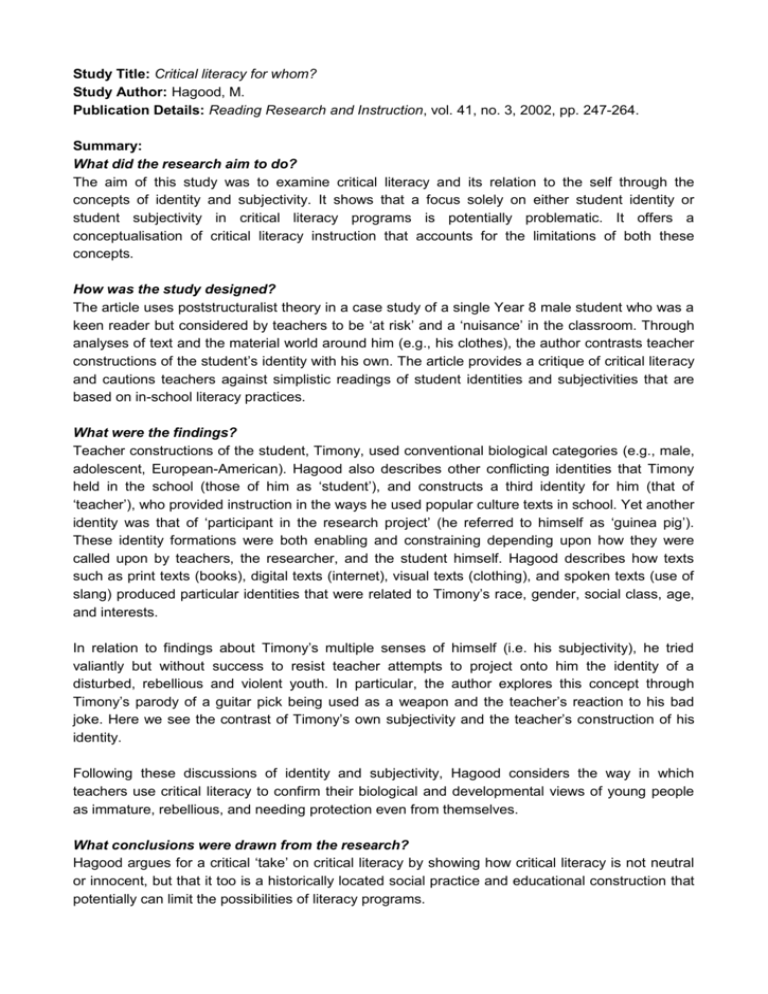

Study Title: Critical literacy for whom? Study Author: Hagood, M. Publication Details: Reading Research and Instruction, vol. 41, no. 3, 2002, pp. 247-264. Summary: What did the research aim to do? The aim of this study was to examine critical literacy and its relation to the self through the concepts of identity and subjectivity. It shows that a focus solely on either student identity or student subjectivity in critical literacy programs is potentially problematic. It offers a conceptualisation of critical literacy instruction that accounts for the limitations of both these concepts. How was the study designed? The article uses poststructuralist theory in a case study of a single Year 8 male student who was a keen reader but considered by teachers to be ‘at risk’ and a ‘nuisance’ in the classroom. Through analyses of text and the material world around him (e.g., his clothes), the author contrasts teacher constructions of the student’s identity with his own. The article provides a critique of critical literacy and cautions teachers against simplistic readings of student identities and subjectivities that are based on in-school literacy practices. What were the findings? Teacher constructions of the student, Timony, used conventional biological categories (e.g., male, adolescent, European-American). Hagood also describes other conflicting identities that Timony held in the school (those of him as ‘student’), and constructs a third identity for him (that of ‘teacher’), who provided instruction in the ways he used popular culture texts in school. Yet another identity was that of ‘participant in the research project’ (he referred to himself as ‘guinea pig’). These identity formations were both enabling and constraining depending upon how they were called upon by teachers, the researcher, and the student himself. Hagood describes how texts such as print texts (books), digital texts (internet), visual texts (clothing), and spoken texts (use of slang) produced particular identities that were related to Timony’s race, gender, social class, age, and interests. In relation to findings about Timony’s multiple senses of himself (i.e. his subjectivity), he tried valiantly but without success to resist teacher attempts to project onto him the identity of a disturbed, rebellious and violent youth. In particular, the author explores this concept through Timony’s parody of a guitar pick being used as a weapon and the teacher’s reaction to his bad joke. Here we see the contrast of Timony’s own subjectivity and the teacher’s construction of his identity. Following these discussions of identity and subjectivity, Hagood considers the way in which teachers use critical literacy to confirm their biological and developmental views of young people as immature, rebellious, and needing protection even from themselves. What conclusions were drawn from the research? Hagood argues for a critical ‘take’ on critical literacy by showing how critical literacy is not neutral or innocent, but that it too is a historically located social practice and educational construction that potentially can limit the possibilities of literacy programs. What are the implications of the study? Critical literacy instruction needs to incorporate the study of both identity and subjectivity. This will assist teachers to understand students in more complex ways rather than through simple binaries of mature/immature, good/bad, stable/at-risk, lazy/engaged and so on. Keywords: critical literacy, identity, post-structural theory, critical social theory, youth culture