"Children make meaning in a multiplicity of ways and employ a

Making meaning through role-play: an exploration of children's linguistic communication within the diversity of play narratives

Rebecca Austen, Sue Hammond, Gill Hope

Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, Kent.

Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of

Glamorgan, 14-17 September 2005

Abstract

"Children make meaning in a multiplicity of ways and employ a multiplicity of modes, means and materials in doing so." (Kress 2000:96)

This paper f ocuses on young children’s interactions and use of language in constructing, negotiating and developing shared narratives in a range of role-playing situations. Our research focuses on explorations of three aspects of children's play:

the role of 'new technologies' in broadening the spectrum of communicative modes incorporated into children’s language and role play in their efforts to make meaning,

the effect of gender-specific patterns of language and social interaction during play on narrative composition,

the ways in which children's designing and making of role-play props supports the development of the play narrative.

This paper is based on the authors' researches into young children's play in the context of their wider social and cultural lives, in both the home and school environments. It brings together three separate insights into the way that young children interact with each other and with play props, that are complementary and mutually informative. Whilst focussing on the development of children's language within role-playing situations, the paper also examines the ways in which children’s meaning-making overspills their playing to influence the later development of designing and story-telling.

Key words:

Play

Early childhood

Technology

Introduction

The UK National Primary Strategy "Excellence and Enjoyment" has triggered changes in many Key Stage 1 classrooms. Building on good practice in Foundation Stage, many Year 1 children spend part of their day engaged in child-initiated activity. Play is recognised once again as a vehicle for learning.

Play is the natural mode through which young children learn. It is not something they are taught or need to be encouraged to do but an innate force that compels them to hypothesise, experiment, explore and invent. It often requires negotiation, commitment, originality and sustained effort.

As researchers with special interest in the play and creativity of young children, we have begun to document and analyse our observations of young children’s playing and to ask the question: how does this natural activity of young children demonstrate their attempt to make personal meaning of the technological and social environments in which they are immersed? To aid this exploration we have each contributed observations in different contexts (home, role play area in an Early Years setting, KS1 class-rooms). Common threads have begun to emerge and we feel as if we “have something here.” We are presenting this paper, therefore, not as an

“answer” but as a starting point and invite our audience to contribute to our research efforts.

The role of 'new technologies' in broadening the spectrum of communicative modes

Context of research observation: Home environment; Researcher: Rebecca Austen

Children will play with w hatever is to hand. (Kress 2003)What children have ‘to hand’ is clearly constantly changing. Not only in terms of ‘toys’ or other play artefacts, but also in their exposure to and engagement with a whole range of cultural experiences. One of which is their interactions with so-called new technologies. My research focuses on how my children (Ben, aged 4 and Ellie aged 6) incorporate their experiences with computers, the Internet and console games into their play.

Smith (2005) reports the need for more r esearch into what she calls ‘computer-based dramatic play’. Whilst there is a developing resource of research into play whilst using the computer (Smith cites Escobedo, 1992;

Labbo, McKenna and Kuhn, 1996; Liang and Johnson, 1999) and the role of televisi on in children’s dramatic play is well-documented (Buckingham 1990, Bromley 1999, Grugeon 2004 et al) there is very little which examines the impact of children’s experiences with computers and games consoles on their play.

The language of ‘new technologies’ is used confidently by my children. At the age of 4 Ben asked me where

‘caps lock’ was on my lap top so that he could enter his name onto his ‘PC Play and Learn’ CDRom. Both children played with the sounds of ‘www.com’ and ‘www.co.uk’ from an early age and would chant them and enjoy the ‘feel’ of them (Grainger 1996). Although I believe that they had heard this through television rather than through their own use, Ellie demonstrated her understanding by suggesting that I try ‘www.actionman.com’ when looking for an action man website – she was aged 5 at the time. Ben used the word ‘click’ frequently and correctly from his first experiences with the computer. At the age of 3, Ben was playing with his cars; he held up a toy car in each hand at abou t head height and slowly turned them to and fro saying “You click on one”. The chosen car was then ‘driven’ round the ‘race track’ (the lounge).

The new technologies have also provided opportunities for creative use of language. Walking to school with

Ben, age 4, he pointed to the ‘dark bits’ – which are the shadows cast by walls, fences bushes and so on onto the pavement and said: “If you tread on the dark bits you get dead. When you get 20 you are (pause) deaded.” He needs a new way of saying and settles for ‘deaded’ a decidedly final sounding term which means that you have run out of ‘lives’ – rather than being given the chance to try again. Ben has ‘made meaning’ using his own words. It is inevitable that children’s experiences of ‘new technologies’ will appear in their play narratives and therefore inevitable that new language, and new ways of constructing language will be necessary to play out those experiences. (Kress 2003)

Ben’s responses in his play are nearly always related to physical movement. He tells his dad, whilst they are

‘playfighting’ that he needs to ‘press x to jump, double to spin and the arrow keys to move’. He tells me he is

‘moving like a monster’ as he side-steps around objects with this arms straight down by his side, mirroring a game he had been playing on the PC earlier in the day. This seems to be comparable to what Scollon and

Scollon (1981) (cited in Meek (2000))describe as the child being both the ‘teller and the told’ – taking on the role of both the narrato r and characters in the story. Pahl (2005) talks about this in terms of ‘multiple identities’ children are both outside of the game, but also taking on the identity of the character they play. This is seen again whilst the children are playing the Lego Star Wars console game. One of the most fascinating things to watch whilst the children are playing the game is Ben’s physical reaction and response. He is clearly caught up in what he is doing, and there is a strong emotional response to the games. His attention is focused on the screen, mouth slightly open and he is invariably sitting at the edge of his seat. At moments of intense excitement Ben often gets up out of his seat, taking his controller with him, and mirrors the action of the character he is playing on the screen. He moves in the same direction as his character and if the character is standing sideways, he too will turn his body slightly to the side. This is nearly always accompanied by jumping up and down and saying things like ‘Yeh, I got him!’ or similar responses to what is happening in the game. This seems to me like a physical engagement with the narrative – a crossover. Ben is both controlling the character in the game and playing out the role of the character itself. This intense involvement in the game will surely have an impact on the roles he plays outside of it.

Creating narratives in Role-Play: gender relationships and discourse

Context of research observation: social interaction and construction of narratives in FS role-play settings

Researcher: Sue Hammond

My particular interest is young children’s construction of narratives in their role-play and whether there are identifiable gender patterns emerging that affect the storying, social interaction and peer relationships.

Conversely, peer relationships could by their nature affect the narratives so many of the interpretations are considered from both perspectives.

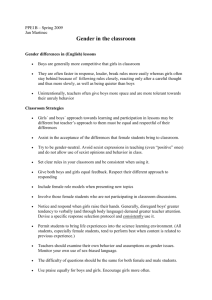

Ryan (2005) cites several research studies (Davies 1989; Mac Naughton, 1994; Jordan et al, 1995), that have found noticeable differences in the behaviours of girls and boys in role-play contexts. She adds to these her own observation that ‘Like many boys…Steven preferred physical strategies to verbal ones to control his world.’

(2005: 107) Whilst I did find this to be a pattern that emerged in some of the role play observed, there were also instances of boys who compromised and utilised verbal skills to negotiate the play and sustain the shared narrative. In each observation the group comprised 4 and 5 year old girls and boys in a Reception class in a

Primary school. There was a significant contrast in the way that stories were developed and the tendency of the girls to plan for their play.

Boys:

During each observation the boys’ narratives were constructed spontaneously as they played in the role-play area and its direction often appeared to be prompted by a prop or an artefact, or through some connection made with another child’s talk. On occasions, this would be an explicit response to the previous speaker but at other times the links were less obvious to an observer. Narratives were frequently developed alongside actions and accompanied by physical demonstrations.

One observation focused on a mixed group of 3 boys and 2 girls in a Reception class and the boys were demonstrably more voluble and active than the girls. This could be attributed to:

The familiarity the children had with each other;

The excitement of exploring a new area, its different artefacts and role opportunities;

The sociability of the boys

The excitable and boisterous characters of the boys involved

The last of these would fit with a stereotypical image of boys and the physical dominance they have in mixedgender groups. However, I feel this could be doing them a disservice and the research needs to pursue it at a deeper level, rather than accept that boys are rowdy and girls are quiet and thoughtful.

It was one of the boys who, in a dispute with Helena, decided to compromise and allow her to take the leading role. This enabled them both to develop their roles further, to continue their narrative and add to its complexities.

Before this was achieved, he had used physical force in an attempt to get her to relinquish the key role they each desired, just as Stephen had in Ryan’s (2005) study.

Girls:

This observation could also suggest that the girls were less sociable or more self-sufficient than the boys, although Helena was compelled to interact with Aaron in order to resolve the dispute over which of them would serve the customer in their shop. Once their dialogue had begun she was happy to continue in her roleincorporating a gentler, higher pitched voice into it-and to extend their story.

In contrast, the second girl moved around the play area smoothly and silently, replying to direct questions but otherwise observing her peers, examining objects and engaging in solitary play. She picked up the telephone and talked into it but made no attempt to involve anyone else. There are again different conclusions that might be drawn from this data, such as:

She was not particularly comfortable or very comfortable (making talk superfluous), with this group,

The novelty of the area encouraged individual exploration rather than collaborative story-making

During another observation, the girls immediately adopted roles in the ‘Doctor’s Surgery’ area and discussed the beginning of their story whilst they donned uniforms. The boys stood watching them until Andrew decided to become involved (see Transcript in Appendix A)

It is clearly the girls who dominate the narrative and are seriously committed to using their cultural knowledge of the context to create their roles and discourse. They draw on a range of specific language, and become distressed when the boys use what they consider to be inappropriate behaviour (i.e. using the medical instruments as guns).

Continuation of the research:

So far the data has yielded many ambiguities about young children’s social interactions and gender behaviours.

Whilst there are identifiable gender patterns, there are still many answered questions about boys and girls roles and narrative constructions.

Playing at being a designer: Gender - an unlikely window

Context of research observation: researching design capability in Key Stage 1.

Researcher: Gill Hope

Browne & Ross’ (1995) observations of young children in free play activities broadly resonated with my own observations in a Year 1 classroom: girls tended to gravitate towards drawing and making small items at tables; boys sprawled across the floor playing with construction kits. Similarly gendered styles were observable within the approaches of Year 2 children's design capabilities. Put stereotypically, the Year 2 boys used design strategies that mirrored of the play styles of the Year 1 boys, and the girls likewise. Put unstereotypically, they’re appeared to be a strong connection between play styles and design styles.

Boys:

In Browne & Ross’ account, boys were observed building models with construction kits, brmm-brmming them around briefly and then taking them apart to make something else. My observations were that boys play and talk through the construction of complex structures, creating the fantasy and its vehicle together, integral with the social action. The vehicle-in-progress is imbued with features (for example, rocket boosters) and the story-line is put on hold whilst essential construction takes place. The narrative is played out in speech and action, especially when in parallel or conjunction with other players.

This on-going development of design narrative, especially in conjunction with others was readily observable amongst the outgoing, sociable main boys’ group in a Year 2 class. They talked their way through every design activity. They freely shared and commented on each other’s ideas in the same way, as they would play with a box of Lego. Design statements beginning with words such as "I'm going to have one that…." would immediately elicit responses. Other boys would make evaluative suggestions, add other ideas, try out the idea themselves, take it further and report back. Several of the de-briefing conversations at the end of a design activity illustrated the extent to which boys had discussed their ideas at planning stage. Such design by discussion facilitated design development and supported those with fewer ideas of their own.

Girls

In contrast to the boy's obsession with constructions that were immediately taking apart, the girls in Browne &

Ross' study tended to make simple structures to support social interaction. In my observations, girls frequently created just sufficient play-props to maintain the story-line. For, example, exploring the dressing up box, Carly

(aged 5) gave a piece of black cloth to Shannon, keeping a larger piece for herself. Putting hers round her shoulders, Carly said:

I'm the wizard. You're the 'prentice. Now, go and fetch the water (unceremoniously shoving a large plastic pot into Shannon's hands).

Whilst sitting making things as a group, the Year 1 girls kept a weather eye on what each other were doing, monitoring each others output and appropriating good ideas without comment, often whilst talking about something else. For several weeks, making baskets out of paper was a favoured free choice activity. Expertise developed in attaching handles with staples, cutting intricate designs into the sides before assembly, adding stylized hearts and flowers, yet their on-task conversation was limited to negotiating sharing resources. They rarely commented on each other's ideas but simply incorporated each new development into their own work.

This discrete appropriation of other's ideas was mirrored in the Year 2 girls' design methods. They talked far less than the boys, usually on the practical (sharing pencils or sellotape) or apparently superficial (colour, decorative feature s) yet their good ideas appeared within each other’s work.

Whereas the boys transferred their construction play styles to the task of designing, the skills the girls transferred were those of the paper-play table. They did not appear to be transferring the rich narrative world of the role-play corner, which they frequently dominated in Year 1. Their abilities in constructing joint fantasies were as strong as the boys, yet it was unusual to observe girls' groups really playing with design ideas in the free-flowing social way that the boys appeared to do.

An insightful reflection on gendered learning, presented by Katz (2003), is apposite. Eschewing neurological explanations of boys' poorer performance in academic subjects, Katz hypothesizes that the most vulnerable boys are those growing up in cultures who images of masculinity are to be "agentic" :

"i.e. to take action, initiative, to demonstrate strength and assertiveness, rather than the easier, passive, accepted submissive of the female in the formal classroom and in the culture in general." (Katz,

2003:17)

I could see reflections of Katz's hypothesis in my boys and girls and in the transfer of their prior learning to design activities. The boys saw these as a chance to be agentic. This was demonstrated most forcefully whilst observing this group of children after they transferred to Year 3. Asked to design a model of the Maze to help

Theseus escape the Minotaur, the boys created a fantasy world around the theme, drawing on their experience with computer games and of reconstructing these games using Lego or other toys. The prior learning that the girls brought to the Maze task was their repertoire of paper and scissor techniques, rather than their rich roleplaying skills, perhaps because these were not the skills they saw as relevant to the task or valued by the teacher. I find that this is something that I want to research further.

Conclusions at this stage:

Our conclusions are, inevitably, tentative and represent a first stage of analyzing our observations of young children at play. What has become clear to us is the way in which young children use play to explore their position in the world, in relation to others and to the wider culture. They bring with them into formal settings a rich understanding of the technological world in which they are immersed. They are beginning to discover and experiment with the gender identities that their society offers them and to exploit those expectations as they see them. They take forward into their experiences of school learning both their developing understandings of the physical and social worlds that surround them and also the roles that they have begun to define and adopt for themselves as agents within that cultural setting.

REFERENCES

Bromley, H. (1999) Video Narratives in the Early Years in Hilton, M. (ed) 1999 Potent Fictions Routledge

Browne, C. & Ross, N. (1993) Girls as Constructors in the Early Years: promoting equal opportunities in maths, science & technology ; Stoke on Trent; Trentham

Bruce, T (2004) Developing Learning in Early Childhood Paul Chapman Publishing

Buckingham, D. (1990) Watching Media Learning Falmer Press

Davies, B (1989) Frogs and Snails and Feminist Tales: Pre-school children and Gender Allen and Unwin; cited in

Ryan, S (2005) Freedom to Choose in Yelland (ed) Critical Issues in Early Childhood Education OUP

Grainger, T. (1996) The Rhythm of Life is a Powerful Beat in Language Matters July 1996

Grugeon, E. (2004) Outside the Playground: children’s talk and play on the playground.

ESRC Research

Seminar Series Children’s Literacy and Popular Culture University of Sheffield

Katz (2003) in International Journal of Early Childhood Vol.31. NO.1; OMEP

Kress, G. (2003) Literacy in the New Media Age London: Routledge

MacNaughton, G (1994) You can be Dad: gender and power in domestic discourses and fantasy play within early childhood, Journal for Australian in Early Childhood Education, 1: 93-101

Meek, M. (2000) in Bearne, E., Watson, V. (2000) Where Texts and Children Meet London: Routledge

Pahl, K. (2005) in Marsh, J. (ed) 2005 Popular Culture, New Media and Digital Literacy in Early Childhood

London: Routledge Falmer

Smith, C. (2005) in Marsh, J. (ed) 2005 Popular Culture, New Media and Digital Literacy in Early Childhood

London: Routledge Falmer

APPENDIX 1

Context: Doctor’s Surgery

Children : Ellis, Jack, Abigail, Ashley, Matthew and Shannon

Field notes

Background: new rp context contains various instruments and uniforms plus different writing materials, posters and booklets. Abigail, Shannon and Matthew immediately pick out uniforms, dress and talk about the roles they will adopt. Ellis and Jack shout excitedly as they explore each item in turn, laughing and putting uniforms against themselves but don’t show any interest in trying them on.

Abigail: (wearing a white coat) One has to be the patient.

Ashley: (stops putting on stethoscope ) I’m going to be the patient.

Ellis: What am I going to do then?

Jack: (lying down and picking up oxygen mask) You can put this on me.

Ellis: What can I be?

( Jack is apart from his peers playing with the doctor’s instruments.)

(Ashley sits on the floor beside Doctor Abigail.)

Abigail: Lift up the leg that hurts. (She examines the leg with one of the instruments.)

Ashley (giggling) That tickles!

Abigail: I’ve got 3 sick patients over here. (To Ashley…) Do you need this? (Offers him the oxygen mask.)

Ashley: I can breathe.

( Matthew now puts on the doctor’s coat that Abigail has removed. Jack is groaning on the floor. Ellis leans down to him and pretends to inject him.)

Ellis: Now you’re alright.

Abigail: (at the table ) That’s Ashley’s test.

Shannon: (taking role of receptionist and writing number of symbols in an exercise book.) That’s Ellis’s test.

(Ellis and Jack start to run around using some of the instruments to shoot each other. Abigail looks distressed, then uses a red pencil and piece of paper to produce a sign similar to a ‘no smoking’, replacing smoking with word ‘guns’.)

Abigail (pointing ): No guns. Can’t you see that sign. No shooting in here.