Rules for Using a Dichotomous Key

advertisement

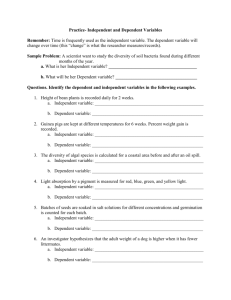

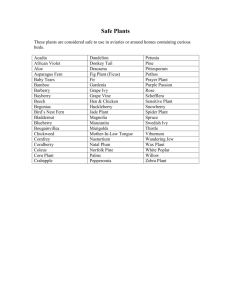

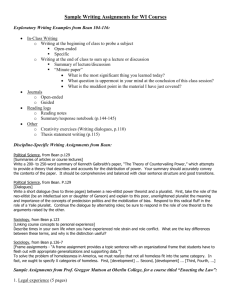

MSC 172 Laboratory #2 Fall 2009 Taxonomic Classification We order the biological world into distinct categories based on relatedness. Taxonomy is the study of those categories. Our system of taxonomy orders all organisms hierarchically, that is, most related organisms grouped together, followed by most related groups, and so on, until all living things are in one mega-group. The smallest taxonomic group is usually the species. Many species can be operationally defined as that group of organisms that can interbreed and produce viable (that is, alive), fertile (that is, able to reproduce themselves) offspring. Because much of the biological world reproduces sexually, this definition insures that the most related organisms will all be classified together as a species. Groups of species – presumably all derived from a single ancestral species – are called genera (singular genus). The Latin, or taxonomic, name of an organism is the genus and species name. For instance, the taxonomic name for humans is Homo sapiens. Homo is the genus and sapiens is the species. Notice that the genus is always capitalized, and species never is. Latin names are italicized when typed, and underlined when written. Never forget these rules!!! What about groups that are bigger than genera? The following table lists the taxonomic categories starting with species, and ending with Domain, the largest grouping. Category Domain Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Example Eukarya Animalia Chordata Osteichthyes Salmoniformes Salmonidae Onchorhynchus tshawytscha Translation Eukaryotes Animals With notochords Bony fish Salmon, trout Pacific salmon and trout King salmon New species are discovered by making repeatable measurements of the degree of behavioral, morphological, and genetic similarity between individuals. The principle being that a group of interbreeding organisms will be more similar to each other than to any other organism. The longer – in evolutionary time – organisms have NOT been able to interbreed, the greater the chance for dissimilarity. How do we measure similarity? It’s not enough to simply say “Hey! Those two organisms look pretty similar; I think they’re probably the same species.” Taxonomists measure these relationships by recording the state or measurement of a character. A character is any repeatable measurement. As mentioned in the last section, behavioral, genetic and morphological characters are usually used. Morphological characters are anything you can measure on the body of the organism, such as the presence or absence of a certain character, colors, meristics (counts), and length. Morphological characteristics will be used in this lab. *As adopted from Cassie Zanca at the Louisana Sea Grant College Program MSC 172 Laboratory #2 Fall 2009 What is a dichotomous key? A dichotomous key is a tool that allows the user to determine the identity of items and organisms in the natural world. It is the most widely used form of classification in the biological sciences because it offers the user a quick and easy way of identifying unknown organisms. Keys consist of a series of choices that lead the user to the correct name of the given item. “Dichotomous” means “divided into two parts.” That is why dichotomous keys always give two choices in each step. In each step, the user is presented with two statements based on characteristics of the organisms. If the user makes the correct choice every time, the name of the organism will be revealed at the end. There are two kinds of descriptions that might be presented to the user of a dichotomous key: qualitative and quantitative descriptions. Qualitative descriptions concern the physical attributes, or qualities, of the item being classified. Examples of qualitative descriptions are such phrases as “contains green striations on top surface” or “feels slick on bottom surface.” Quantitative descriptions concern values that correspond with the item being classified. Examples of quantitative descriptions are such phrases as “has 10 striations on top surface,” “has 8 legs,” or “weighs 5 grams.” Knowing the difference between these two types of descriptions can be immensely beneficial for creators and users of dichotomous keys. There are two ways to set up a dichotomous key. One way is to present the two choices together, and the other way is to group by relationships. Let’s demonstrate the difference between these two types with a legume example: Type 1 – Presenting 2 choices together 1a. 1b. Bean round Bean elliptical or oblong Garbanzo bean Go to 2 2a. 2b. Bean white Bean has dark pigments White northern bean Go to 3 3a. 3b. Bean evenly pigmented Bean pigmentation mottled Go to 4 Pinto bean 4a. 4b. Bean black Bean reddish-brown Black bean Kidney bean Type 2 – Grouping by relationship A. Bean elliptical or oblong B. Bean has dark pigments C. Bean color is solid C. Bean color is mottled D. Bean is black D. Bean is reddish-brown B. Bean is white A. Bean is round Go to B Go to C Go to D Pinto bean Black bean Kidney bean White northern Garbanzo bean *As adopted from Cassie Zanca at the Louisana Sea Grant College Program MSC 172 Laboratory #2 Fall 2009 Procedure In this lab, you will work in groups at one or more taxonomy stations – depending on time – to try and identify the species on the table. Between stations, organisms are quite distinct (Mollusks, Crustaceans, Fish, Sharks, Marine Mammals), but within each station, species are relatively similar. Your job is to figure out who’s who. You will find a group of organisms and a dichotomous key at your station to help you make your decisions. Dichotomous keys are unfortunately filled with taxonomic and anatomical language that is difficult to understand (or even pronounce in some cases!). Don’t despair – refer to the labeled diagrams to find the correct body parts. Each member of your group is in charge of 2 organisms. One person should be assigned as the key reader. This person will read out the relevant lines in the key, waiting for all group members to check their organisms. Record the organism number, the number you are directed to go to next, or the species if you have reached the endpoint, and common and scientific names - on the attached data sheet. Rules for Using a Dichotomous Key 1. Always read and consider both choices, even if the first one seems to be appropriate. Jumping to conclusions may lead to the wrong classification of the item. 2. Always understand the meaning of the words used in each choice. Define the term. If you are not sure of the meaning, look it up in the dictionary. Never guess, as this could lead to the wrong classification of the item. 3. When there are measurements given in the choices, use the appropriate measuring tools or adjust them to match your own set of tools. For example, if a key measurement is given in centimeters but your ruler is divided into inches, convert the centimeter measurement into inches. Do not approximate and do not guess. Measure. 4. If you are classifying a living or once-living thing, do not base your conclusion on a single observation. Living things almost always exhibit variability, so it is better to study many specimens in order to be sure that your results are representative of the majority. 5. If you are left with two possible answers, read the description of both and decide which one seems to fit your specimen more precisely. 6. Once you have identified all your organisms, do not assume that it is correct. If there is any doubt, recheck the description of the organism to see that it appropriately matches. If it does not, then an error was made somewhere in key development. *As adopted from Cassie Zanca at the Louisana Sea Grant College Program