Lecture Notes 4: Skepticism and Certainty

advertisement

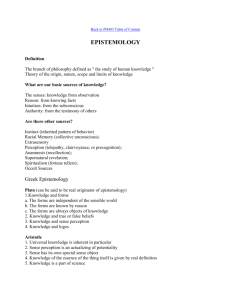

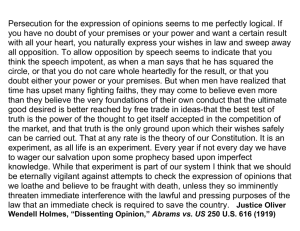

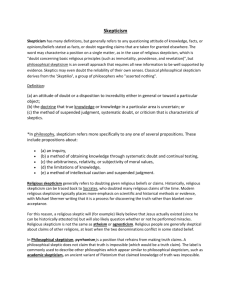

Philosophy 024: Big Ideas Prof. Robert DiSalle (rdisalle@uwo.ca) Talbot College 408, 519-661-2111 x85763 Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday 12-2 PM Course Website: http://instruct.uwo.ca/philosophy/024/ Certainty and Skepticism: some basic questions (skepticism: from the Greek , to examine, inquire) Can any human belief or perception be placed beyond doubt? Once the possibility of doubt has been admitted, can it ever be removed? Can any beliefs still be justified as knowledge? Are there any beliefs that are worthy of being accepted as foundations for other beliefs or inferences? Can a genuine distinction be made between appearance and reality? Can skepticism itself be a consistent point of view? Some basic skeptical and non-skeptical attitudes: Dogmatic skepticism: Nothing can be known. Nothing is true. All human claims to knowledge are false. Pyrrhonian skepticism: Certainty is impossible, so the wise person should suspend judgment about theoretical matters. Empiricist foundationalism: The senses provide the ultimate criteria for justifying belief. Rationalist foundationalism: The senses give subjective or even deceptive appearances, and only reason provides a foundation for certain knowledge. Authoritarianism: Certain persons (e.g. priestly authorities, authors of sacred books) are empowered to know and to speak the truth on fundamental matters. Some underlying principles of skepticism Relativity of perception: Perceptions vary according to circumstances of -- time and place, --physical conditions, the nature of the object, and the nature of the individual perceiver. Conclusion: Contrary to the empiricist, our own immediate sensations are no guide to objective circumstances. The problem of infinite regress: Any rational argument must depend on premises. And these premises must be deduced from other premises. And those most be deduced from still other premises. And so on and on… Or, the problem of conventionalism: In order to avoid an infinite regress, we can simply choose a principle as an axiom, and so refuse to justify it. But since the axiom cannot be deductively justified, it is arbitrary. Conclusion: Contrary to the rationalist, reason cannot provide a foundation for true belief. The problem of human variability and frailty: For every opinion held by any reputable human being, there is a contrary opinion that has been held by equally reputable human beings. Every opinion that now seems foolish has been, at some other time or place, regarded as absolute truth by reputable authorities. Generally, what human beings regard as certain varies according to history and culture. Conclusion: Contrary to the authoritarian, no human beings can be regarded as having some special insight into the truth. Montaigne: Skepticism to mitigate doubt Credulity: Excessive trust in reports of others Incredulity: Excessive confidence in the wisdom of one’s own judgment. Skepticism: a sense of the fallibility of human judgment “We must bring more reverence and a greater recognition of our ignorance and weakness to our judgment of nature’s infinite power….For to condemn [improbable things] as impossible is rashly and presumptuously to pretend to a knowledge of the bounds of possibility.” Descartes: “Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and Searching for Truth in the Sciences” “I do not intend to teach [the method], but only to speak about it. For as you can see from what I say of it, it consists more in Practice than in Theory, and I called the treatises…Essays in this Method, because I hold that the things that they contain could not have been discovered without the method, and that through them you know its value.” Discourse on the Method: An analytic method of distinguishing truth from falsehood, and of building scientific knowledge on secure foundations Optics: A mathematical theory of the reflection and refraction of light, including the discovery of the Law of Refraction Geometry: The invention of modern analytical geometry, including the reduction of geometrical curves and figures to algebraic relations Meteorology: A study of atmospheric phenomena, including a derivation of the colours of the rainbow from principles of optics. (Descartes, 1637) Rules of the “Cartesian method”: Accept nothing as true except what is apprehended so clearly and distinctly as to be beyond any doubt. Divide each difficulty into as many separate parts as is possible and necessary to resolve them. Begin with the objects that are the simplest and the easiest to know, and gradually ascend to the most complex and difficult-even assume such an order if none exists naturally. Make such a complete review and enumeration, at the end, as to be sure that nothing important has been omitted. Leibniz’s gloss: “Take what you need and do what you must, and you will get what you want.” The Cartesian skeptical method (“radical doubt”): Turning doubt against itself What would happen if I systematically attempted to doubt absolutely everything? Could such an attempt really succeed? Or would I discover that there are certain principles that it is absolutely impossible to doubt? If I begin by treating all my ideas as false, will I discover that my mind contains ideas that bear unmistakable marks of truth? (Descartes, Meditations, 1641) Cogito ergo sum: “I think, therefore I am.” “While I wished to think that everything was false, it was necessarily the case that I, who was thinking this, was something.” “…this truth, I think, therefore I am, was so firm that all the most extravagant assumptions of the sceptics were unable to shake it…” “…from the very fact that I was thinking of doubting the truth of other things, it followed very evidently and very certainly that I existed….” Now that we know one certain truth, we ask, in what does its certainty consist? What rule can be developed for recognizing certain truths? Nothing convinces Descartes of the truth of “Cogito, ergo sum,” except the fact that he clearly and distinctly perceives it to be true. Therefore “I could adopt as a general rule that those things that we conceive very clearly and distinctly are true. The only outstanding difficulty is in recognizing which ones we conceive distinctly.” Can ideas have “marks” that tell us whether they correspond to something real? Descartes: From my doubts I know that I am limited and imperfect. But the idea of God has such perfection in it that I know that its cause must be something outside of me, i.e., a perfect being. Nothing in any other idea implies the existence of the corresponding thing. I can be certain of the properties of a triangle, but nothing I can know about the essence of a triangle can tell me whether there is such a thing as a triangle. But the idea of God contains existence in its essence. That God exists is as certain as that a triangle has three sides. (Ontological Argument)