The Imposition of Dispositions: Is this What Aristotle Meant

advertisement

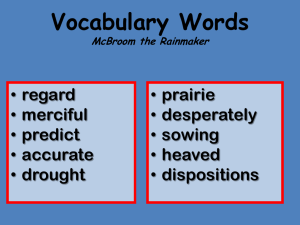

Dispositions An Inquiry of NCATE’s Move into Virtue Ethics by Way of Dispositions (Is this what Aristotle meant?) NCATE is not merely an accrediting agency – it is a force for the reform of teacher preparation. As institutions meet the standards of NCATE, they are reforming themselves . . . . In NCATE’s performance-based system, accreditation is based on results -- results that demonstrate that the teacher candidate knows the subject matter and can teach it effectively so that students learn. (NCATE President Arthur Wise 2001) An impulse to professionalize the field of teaching has been a part of the American landscape since the colonial Puritans first required clergymen, who in many townships held the dual post of Teacher, to earn credentials through a university education (Morgan 1988). During the early twentieth century the effort to professionalize strengthened with the spread of the mass public school systems throughout the nation and the increase in the number of normal schools and university schools of education. This endeavor has persisted into the new century, given an updated urgency by such national reports as Carnegie Foundation’s 1986 report, A Nation Prepared: Teachers for the 21st Century, by national agencies such as the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) and by “effective teacher” research (see e.g. Wise 1999, 2001;Gitomer & Latham 1999; Feistritzer 1999; Darling-Hammond 1992, 2002; Educational Testing Service 2000; Rivkin et al. 1998;Sanders & Rivers 1996; Yinger and Hendricks-Lee 2000; ETS 2000; Katz 1993; Collinson et al. 1999; Collinson n.d. ;Slavin 2002). This latest round of reform has moved beyond earlier attempts to codify professional knowledge and skills. Teacher education reform agencies, including NCATE (founded in 1954), the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) and the Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC), a project of the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), have now moved into a new phase of professionalization -- to assess a teacher candidate’s disposition. By this I mean that Dispositions 2 faculty will have to determine if the teacher candidate’s internal existence aligns with acceptable professional virtues and dispositions, which are to be adjusted if necessary. It appears that reform agencies are attempting to follow the patterns of success experienced by elite professions. Professions such as the medicine and law have been able to convince society that their members possess specialized skills and knowledge that should be valued and rewarded. To become a member an individual has had to internalize the ideological assumptions embedded within what each profession considered legitimate ways of knowing and behaving, historically scientific, technical and abstract (Yinger and Hendricks-Lee 2000). This has not been a difficult feat. Those would be members disposed toward what the professional discourse historically regards as virtues have been compensated with economic and social status and occupational autonomy. These rewards are wed to a virtue ethic principle: that for one’s thought and feelings to be in harmony with professionalized ways of knowing is to truly engage in a “good life” and join a small, elite community within the larger cultural context. However, as many critics have pointed out, those advocating the professionalization of teaching cannot guarantee such economic or philosophical compensation (Densmore and Burbules 1991; Labaree 1992). Nonetheless, educational reformers in favor of intensified professionalization have ventured into this messy territory of virtue ethics. Whereas before NCATE held college of education faculty accountable for proving that each pre-service teacher had mastered certain knowledge and skills, new policies and standards now dictate that faculty must generate evidence as to whether the teacher candidate is the right sort of person, to borrow a phrase from ethical philosopher Edmund Pincoffs (1986). That such a push to compel teacher educators, and so teacher candidates and eventually all K-12 teachers, to personify a particular type of thinking and feeling to be legitimized as a teacher, obliges an interrogation beyond the mechanics of Dispositions 3 how to implement these requirements. There are the questions of whether dispositions, as vaguely spelled out in the NCATE standards (2002) can be assessed at the college level, much less taught in a way that would lead the teacher candidate to alter his or her already settled dispositions. There simply may be too little time and access. There is also the issue of whether dispositions toward virtues such as social justice, caring and honesty, which NCATE documents present as desirable, will fail to leave an impression upon preservice teachers. Historically, successful professions have legitimized their social and economic position and prestige by valuing and being disposed toward “male” oriented (Gitlin 1996) “competitive, rationalistic, task-centered and abstracted from contexts” approaches to work (Labaree 1992, 132).These dispositions have been reinforced in the general process of schooling, as part of the hidden curriculum and academic achievement discourse, according to those who analyze schooling from a critical lens (e.g. Bowers and Flinders 1990; Doll 1998;Cherryholmes 1988; Zeichner 1991). By the time an individual has reached college, the institutionalized dispositions within which he or she has been inculcated, technical in nature and so assessable through standard tests and observations of field work, have become deeply rooted habits of thought and feeling, not easily dug up and displaced. Aristotle’s work in virtue ethics clarifies this problem. Aristotle defined the term disposition as the nature of a virtue or vice in relation to the agent and the possession of a particular frame of mind in any given ethical or moral situation. He explains that a disposition is one thread in a highly complex and pervasive ethical existence that begins with a child being inculcated into virtuous habits as defined by a community, though with no expectation that the child will understand the nature of the moral virtues. Not until adulthood and only if morally and intellectually well equipped, is an individual prepared to move beyond obeying and practicing virtue out of fear or shame of retribution to a deeper Dispositions 4 contemplation (theoria) of a virtue’s nature in relation to the agent him or herself. Only then are reason and emotion harmonious and virtue acted upon out of love and understanding rather than fear of reprisal or as an unrecognized ideological assumption (Broadie 1991). Such a proper dispositional stance toward a virtue develops over a long period of time and depends upon a broad range of experiences. Hence, assessing the dispositional stance of a teacher candidate is problematic. It is also questionable to demand a teacher candidate shed certain dispositions and virtues for which they have been rewarded in their schooling in favor of ones that historically have not been privileged. However, as Aristotle indicates, dialogue about and theorization (theoria) of such issues by teacher candidates and faculty are certainly advocated and even necessary so that each can at least begin the process of becoming critically aware of embedded assumptions about what is virtuous or not for an individual who desires to become a teacher. Professional discourse as privileging “male” and technical dispositions Dispositions: The values, commitments, and professional ethics that influence behaviors toward students, families, colleagues, and communities and affect student learning, motivation, and development as well as the educator’s own professional growth. Dispositions are guided by beliefs and attitudes related to values such as caring, fairness, honesty, responsibility, and social justice. For example, they might include a belief that all students can learn, a vision of high and challenging standards, or a commitment to a safe and supportive learning environment. (NCATE 2001 Professional Standards glossary, 53) Dispositions 5 The term professional appears throughout NCATE and INTASC documents: “We believe states must strive to ensure excellence in teaching for all children by establishing professional licensing standards and learning opportunities which enable all teachers to develop and use professional knowledge, skills, and dispositions on behalf of students” (INTASC 1992, Preamble, emphasis mine). The pervasiveness of this discourse is apparent in its extensive national coverage by way of NCATE, INTASC as well NBPTS. As of this writing, 46 states and more than 600 colleges and universities have either chosen or have been dictated to by state education departments to undergo NCATE accreditation, with INTASC, NBPTS and NEA involved in the development of standards. According to NCATE numbers, 28 states have aligned state standards with those of NCATE (nate.org/ncate/m_ncate.htm), generating a condition in which the national discussion on education reform occurs solely through the discourse of professionalism. According to Abbot (1988, 8), the term professional refers to “exclusive occupational groups applying somewhat abstract knowledge to particular cases.” This has implications for the new NCATE emphasis on dispositions and virtues. The term dispositions appears throughout the 2001 and 2002 Professional Standards document, always as one of a tripartite nexus from which an effective teacher is constituted: “knowledge, skills and dispositions.” Each standard marks this phrase as the lens through which all pre-service teachers and college of education faculty will be and assessed. To a great extent, in this most recent NCATE treatment of dispositions, virtues such as caring, fairness, commitment to students and a nurturing environment and honesty contravene what have historically been considered virtues and dispositions of professionalism – rationalized practices, disinterested application of research, abstract context-free knowledge and technical reflection. Dispositions 6 In fact, NCATE dispositions and virtues appear to pull from an earlier point in American history when normal schools prepared female elementary teachers and universities prepared administrators. Administrators, all of whom in the early twentieth century were male, were the first to be successfully professionalized. These men [sic] were credentialed by schools of educations, whose faculty – also male – struggled for academic legitimacy by creating a research model acceptable by traditional sciences and liberal arts within the university. The university approach to professionalism depended upon the mastery of knowledge and skills to be applied at work as determined by research, which was occupied by certain inherent ideological assumptions about different groups in society, such as gender differences, as well as assumptions about what constituted legitimate knowledge (Gitlin 1996). Only those specially trained and credentialed are able to access this abstract knowledge, which had become the knowledge of most worth over the last few centuries due to its association with science. However, even more significant was the belief that males had some natural capacity for this form of rationality, and that it somehow defined the inherent male disposition. Women were considered to neither have the capacity for nor interest in such knowledge and so were forbidden access to it (Gitlin 1996). Schools of education were not immune to these university conditions. Schools of education professors, to gain legitimacy and status within the university, appropriated knowledge approaches and dispositions associated with the male-oriented condition of academia. In doing so, schools of education reinforced the already powerful positions of school administrators, all of whom were male and who were disposed to approach the institution of school as a management, bureaucratic problem in need of a top-down solution, which research appeared to justify (Gitlin 1996; Labaree 1992; Tyack and Hansot 1982). However, the dispositions and virtues provided by NCATE as examples have Dispositions 7 historically been linked with gendered assumptions about how women naturally teach. During the late 1800s and early 1900s such female oriented dispositions and virtues comprised what normal schools, where young women attended to prepare to teach before losing students to university schools of education, articulated as the right sort to become a teacher. This individual was to value commitment to serving students, nurturing, childcentered and experiential learning and concern for student welfare, rather than the mastering of a specialized form of abstract knowledge to be applied. Universities did not value these dispositions and virtues, in part because they did not fall into professionalism inhabited by scientific measurement and control. The acts of measuring and sorting within the university reflected what many Anglo-protestant middle-class Americans had embraced during the late 1800s (White 1969; Wiebe 1967; McKnight in press). Gitlin (1996) argued that normal schools wanted to create a different form of professionalization based upon the socially constructed female dispositions. However normal schools had to eventually compete with schools of educations, which had evolved into the sites where school administrators received their professional credentials through a much different discourse. The university professional discourse further entrenched socially constructed gender differences between teacher and administrator, as well as gave power over the institutional sites to the administrator through the credentialing process. In other words, the administrator was rewarded with professional autonomy long before teachers attempted to claim such status. The professional discourse functioned to support the bureaucratic top-down method of running schools, and also generated policies that located control over teachers, curriculum and students within the administrator’s realm (Burbules and Densmore 1991; Labaree 1992). An effect was the internalization of the socially constructed male virtues and dispositions, well established within a nearly 300year old American university culture. Abstractness, context-free knowledge and tasks, Dispositions 8 technical reflection, task orientations, disinterested application of skills in a technical manner, ethical behavior as clearly delineated listing of do’s and don’ts, competition, scoring and didacticism all became the most reasonable and virtuous dispositions (Labaree 1992). These dispositions and virtues became privileged throughout all forms of schooling as the administrators left the university and assumed leadership roles in their local schools. In time these dispositions became hidden and normative ways of thinking and feeling about the function of school. The normal school construction of professionalism failed to make an impression upon the formal preparation of teachers once these programs were housed within schools of education. The normal schools disappeared over time as women began to enter universities, taking with them the possibility of developing alternative professional dispositions and virtues aligned with the socially constructed female virtues and dispositions. The defeat of the normal schools by universities is significant. Once teacher preparation was located within schools of education, teacher educators experienced pressure to appropriate the same scientific model of studying the act of teaching to develop the sort of legitimacy that educational researchers who prepared administrators received. The belief was that professional knowledge was scientific and hence quantifiable and measurable, which provided proof to the population at large that the profession possessed the skills and know-how to control outcomes. In other words, the movement began the rationalization of the classroom (Labaree 1992). This rationalization process has been governed by a faith that effective teaching could be neatly fit into quantifiable categories evaluated in terms of usefulness in producing some desirable outcome. The desired outcome for the reformers calling for further professionalization of the field is ultimately student learning, which, in turn, is considered dependent upon the behavior of the teacher. To follow through with this logic, a teacher’s behavior is Dispositions 9 dependent upon his or her disposition, his or her internal relation to the virtue at hand. Hence, if the rationalization process is to be followed, then the disposition must somehow be identified, measured and explained. Viewing the professionalization of teachers from this lens was evident even in the early 1900s. Gitlin (1996, p. 600) quotes University of Chicago Professor Charles Judd’s 1929 remarks to this end: We measure the results of schoolwork today with a precision far beyond anything that we hoped for two decades ago when the measurement movement was in its infancy . . . . I hold that teacher education institutions of this country have it as their major duty to study educational problems critically and scientifically and to make available for the whole teaching profession the best results of such study. (Judd, NEA Proceedings, 878-879) An effect of this perspective of analyzing the act of teaching through the lens of science was the ideological assumption that for a teacher to become a professional, he or she must embody the virtues of measurement and rationalization. In the dichotomous thinking associated with Western rationality, female dispositions would be unprofessional. Even though teachers who possessed female dispositions could be good teachers, they were not professionals as defined by the socio-cultural framework of the university. And though calls for the professionalization of teaching continued, for the most part it resulted in the expectation that a female internalize dispositions socially attached to male thinking and feeling: “Apparently thinking of teaching’s femaleness as unprofessional, the professionalizers seem to be trying to reshape the female schoolteacher in the image of the male physician” (Labaree 1992, 133). Teacher educators were to do the scholarly research that was to transform the act of teaching into a research driven practice transmittable to all teacher candidates by experts located within the university. NCATE’s document for professional standards Dispositions 10 (2001, 2002) asserts that the knowledge and skills of teaching have finally been researched and identified: “The profession has reached a consensus about the knowledge and skills a teacher needs to help P-12 students learn” (8). If a teacher candidate believes in this apparent consensus, he or she will be able to “explain instructional choices based on research-derived knowledge and best practice; apply effective methods of teaching students . . .” (NCATE 2001, Professional Standards, 4). In fact, at one point NCATE’s Professional Standards document states: “Candidates for all professional education roles develop and model dispositions that are expected of educators . . . . The unit systematically assesses the development of appropriate professional dispositions by candidates” (2001, 19). The indication is that NCATE is solid in its association with the professionalism’s dependence on demonstrable outcomes and performance assessment. However, at the same time NCATE officials have acknowledged the problems of assessing such dispositional stances created by a historical discourse of professionalization based upon male oriented university research, which has defined the bureaucratic power of administrative control in the institution of schooling. NCATE Professional Standards document states: “Dispositions are not usually assessed directly; instead they are assessed along with other performances in candidates’ work with students, families, and communities” (NCATE 2001, 19). NCATE has taken a page from normal schools by adding dispositions that have been associated with socially constructed female attributes not historically fitting within the dominant framework of university-driven professionalism (Kraft 2001; Gitlin 1992; Labaree 1992). However, the male dispositions and academic virtues stated above have long been supported by the bureaucratic structure of schooling and are easily assessable through tests and discrete practice demonstrations that teacher candidates engage in. Such organization and control of knowledge has been the policy of many successful professions. A doctor diagnosis a Dispositions problem correctly, applies the correct healing method as determined by research and the patient physical state improves. That is a seemingly assessable outcome. The doctor is simply disposed toward reliance upon the dispassionate application of abstract knowledge. However, dispositions such as valuing social justice and diversity, being committed to the learning of children, are much more difficult to assess in ways that are scientific, a necessary condition of the historically dominant mode of professionalism By the time a student arrives at college, he or she is quite familiar, even comfortable, with the normative and expected dispositions lodged with the language of professionalism that privileges academic achievement and technical competence, which have become firmly entrenched virtues, though not always as consistent classroom realities (Doll 1998; Labaree 1992; Kraft 2001). Intended or not, NCATE’s push toward professionalism, with measurable student learning and commitment to professional standards dictated by research practices, actually serve to perpetuate the technical approach to university professionalism despite attempts to reconceive teacher professionalism to include alternative virtues and dispositions (Labaree 1992; Burbules and Densmore 1991). As Labaree writes: However, while opposing bureaucratization, the movement promises to enhance the rationalization of classroom instruction . . . . The teacher professionalization movement promotes a vision of scientifically generated professional knowledge that draws heavily on the movement’s roots in formal rationality. It portrays teaching as having an objective empirical basis and a rational structure . . . . Teaching would become more standardized – that is more technical proficient according to scientifically established criteria for accepted professional practices (1992, 147). 11 Dispositions 12 This creates a quandary for NCATE. Along with its partners in reform, NCATE calls for pre-service teachers and teacher educators to embody two different sets of values and dispositions that in teacher preparation have been mutually exclusive. NCATE documents (2001a, 2001b, 2002) indicate that students must disassemble the deeply embedded rationalized, male dispositions that have controlled the institution of schooling for a century through the professional practices of administrators and replace them with dispositions that were apparently privileged by normal schools more than a century ago. These dispositions are regarded by university, research-driven professionalism as not integral to the application of knowledge and skills (Kraft 2001). Why the so called female dispositions will not make inroads into the university training of teachers, as long as the research driven professionalism maintains its power in the university, becomes even more evident once one explores how Aristotle handled dispositions in his virtue ethic. The place of dispositions in virtue ethics When Aristotle pondered the problem of ethics, the arc of his thought was given structural support by the language of vices and virtues, the often subtle, complicated and culturally contextualized ideals that he believed an individual must possess to achieve happiness (eudaimonia: also translated as human flourishing). Pincoffs (1986) explains Aristotle’s concerns: “[T]he leading question concerns the best kind of individual life and the qualities of character exhibited by the man [sic] who leads it. Again, a necessary preliminary is the study of types of men, of characters, as possible exemplars of the sort of life to be pursued or avoided” (16). According to Aristotle, what form a vice or virtue takes is not static but instead historically situated within a particular community (koinonia: common bond that holds a group together; also translated as association of common interests). Each given community determines the preferences of those living within the social network of that Dispositions 13 time and place. From his historical situation, Aristotle addresses the issue of which human qualities should be preferred and which should be grounds for avoidance by individuals who share communal ties and obligations. His arche is that humans are inherently social creatures whose ultimate goal should be to achieve arête (often translated as excellence in terms of performing one’s function in life well) and the good life through interaction with those who share some sort of communal ties. Important is not just the possession of virtues to get along with others, but to get along in a way that sustains civic friendship (philia). As Aristotle states, one of the main goals of moral wisdom is to preserve communal life as just and productive (NE, Bk. 1, 7, 1097b: Ostwald translation). By this Aristotle is not saying that only external relations are significant. To truly work, which for Aristotle means to sustain the possibility of justice and human happiness, the internal must be in harmony with action in the world. As such, dispositions within the discourse of virtue ethics involve not just an externalities regulated by ethical codes, but individual internal states or desires in relation to some particular virtue or vice that will effect the material world. Aristotelian scholar Sarah Broadie (1991) provides a glimpse into how Aristotle constructed dispositions: “A virtuous person is one who is such as to, who is disposed to, act well when occasional arises. And so far as ‘acting well’ implies not merely causing certain changes in the world, but doing so in the right frame of mind or with right motive, a disposition to act well is also a disposition to act in the right frame of mind” (58). A disposition by definition is connected to some specific emotion or desire toward a virtuous or vicious end. From this simple description, one cannot necessarily argue against teacher education reformers impulse to identify desirable dispositions, for that desire is, obviously, quite ancient. Dispositions 14 It is not unfair to say, then, that dispositions, of which teacher education reformers speak, specifically in terms of the emotional condition of human existence (affect), seem to represent in the discourse of virtue ethics an important step toward the attainment of particular virtues. However, not all affective components (emotional or desirous) are dispositional. For instance, if I get upset with my child for knocking over the orange juice when generally I would not, then the emotion and frame of mind is not connected to any disposition. A dispositional state has to be re-occurring. Also, a recurrent emotional reaction or desire to produce a goal that is not also coupled with a habit of acting in a specific way from those emotions or desires is also not a dispositional emotion or desire. If I desire that academic freedom is absolute when it comes to what I do within and how I go about handling my college course, but then allow others in administration, state agencies, students or colleagues to decide such issues, then I do not possess a proper dispositional desire. Or, if I desire for teacher candidates (who not long ago were simply called students, then became pre-service teachers) to become advocates and practitioners of social justice, but then turn around and advise them to not follow through with such beliefs as they may cause upheaval in the school or loss of job due to the institution’s unwillingness to change, then I do not possess a proper dispositional desire. Hence, while possessing a certain desire is necessary, it is not sufficient to produce a disposition. The desire must be connected to a particular goal, a virtue, and must reoccur in each situation as the context changes, which in everyday life it does quite rapidly from one community to the next. Aristotle writes: “Virtue then is a settled disposition of the mind determining choice of actions and emotions, consisting essentially in the observance of the mean relatives to us. This being determined by principle, that is, as the prudent man would determine it (NE, Bk. 2, 6, 15: Rackham translation). When Aristotle uses the phrase “settled disposition,” he is referring to the moment when a Dispositions 15 disposition connects to particular habits, a patterned way of acting and reacting to various circumstances. Such a definition seems to indicate that a disposition then is the same as a habit. Aristotle makes a distinction here: Habit differs from disposition in being more lasting and more firmly established. The various kinds of knowledge and of virtue are habits, for knowledge, even when acquired only in a moderate degree, is, it is agreed, abiding in its character and difficult to displace . . . . By a disposition, on the other hand, we mean a condition that is easily changed and quickly gives place to its opposite . . . . Habits are at the same time dispositions, but dispositions are not necessarily habits. (Works, Organaon, Categories, 8, 8b27-30, 35-36, 9a10-11) One could be disposed toward irritability, but if the context and environment changes that disposition could shift to its opposite, cheerfulness. Simply, a disposition is not a guarantee that a virtuous outcome will occur. A virtue is a live action and begins with a disposition, which in itself can only bring out the conditions appropriate for a virtuous outcome to occur. A virtue requires the sum total of having the right desire and the right reasoning in order to make the right choice that will bring about virtuous conditions and possibly even outcomes: “Since choice is a deliberate desire, it follows that, if the choice is to be good, the reasoning must be true and the desire correct . . . . [I]n intellectual activity concerned with action, the good state is truth in harmony with correct desire" (NE, Bk. 6, 1139a, 2, 24-27: Ostwald translation). However, to engage in this virtuous activity requires very specific kinds of habits; ones that operate from what Aristotle called the doctrine of the mean, which involves three dispositions -- the correct one situated between two extremes. Dispositions 16 For instance, to have a courageous disposition is to repeatedly be able to confront danger with emotional rectitude (controlled fear) and with a reasonable aim of producing or protecting some good (e.g. others lives). To have a foolish disposition is to repeatedly confront danger (without any fear) and without a reasonable aim of producing or protecting some good (e.g. to die for nothing). These specific kinds of habits are related to dispositions in that the individual had a inclination or desire to be courageous, but it took the development of these very specific habits to make sure that the condition of courage translated into virtuous action rather than falling over into a vice, such as foolishness. One who is merely disposed toward courage may, in the end, engage in an act that results in a vicious outcome. Beyond choosing courage as a virtue to which one should be disposed, specific kinds of habits that link to such a virtue must be attached that reflect what Aristotle called the mean, which is supposed to protect against well-intentioned dispositions that fail to arrive at the chosen virtue. However, these habits are not merely instrumental acts or strategies that teacher research has determined lead to a particular outcome within an individual or between individuals. Twentieth Century ethicists spent a great deal of time attempting to do just that and failed (Bauman 1984). As discussed above, and which NCATE documents appear to recognize, one must engage in a virtuous activity from a dispositional frame of mind that truly accepts and believes that his or her disposition will create the conditions by which virtue can emerge and flourish. In effect, both Aristotle, as a representative virtue ethic, and teacher education reformers seem to desire positive effects, though each define them differently. For Aristotle, the positive effect is the attainment of virtue and possibility of human flourishing and communal friendship, though none of this is guaranteed. One can only help the conditions favorable for the virtue to emerge, but not secure this outcome with certainty, unlike the desire upon which NCATE’s professional discourse operates. For Dispositions 17 the professional discourse, certainty of outcomes is the whole point. And this situation is problematic when understood from Aristotle’s virtue ethic, which does not operate in such a strategic and narrow manner. In effect, as mentioned above, specific habits must be developed within the individual for a disposition to develop into a virtue, habits which, according to any basic virtue ethic, begin early in an individual’s life and encompasses the whole of the individual’s being in every act and thought rather than in particular external activities or jobs. A disposition is not a strategic instrument one uses here or there and then puts down when finished. A person's dispositions or patterns of action can be virtuous or vicious and are not attached to any particular position in life. In other words, a virtue is a virtue for all and not just for a law professor, an educator or an education professor or pre-service teacher (Pincoffs 1986). As Pincoffs points out, if each work situation developed a list of specific dispositions and virtues appropriate only for that particular job, this would be a bizarre condition indeed. One would be left with an arbitrary listing and enumeration for each role he or she played in life. That one’s whole existence cannot be morally and ethically compartmentalized, and that dispositions must connect to virtuous habits early in an individual’s life, is significant for NCATE’s emphasis upon transmitting and assessing dispositions at the college level. For dispositions are not items to check off as tasks completed and graded by some kind of rubric or determined by a code of ethics unless they are defined in terms of the historical male oriented dispositions as discussed above. Nor are dispositions, once settled over time into virtuous activity, easily adjustable as many current teacher educational reformers seem to believe and advocate, as indicated in the above discussion on the self-surveillance of the reflective practitioner seeking to adjust his or her thoughts and actions to what works best for students to learn. Which brings us to issues that loom Dispositions 18 over any desire to implement dispositions at the college level: time, teaching and the lack of understanding as to what virtues, moral or intellectual, do teacher education reformers really desire. Of time and teaching dispositions For Aristotle, virtues are broken down into two types: intellectual and moral. The intellectual virtues, such as “theoretical wisdom, understanding and practical wisdom . . . owes its origin and development chiefly to teaching, and for that reason requires experience and time” (NE, Bk.1, 1103a, 6-7; Bk. 2, 1103a, 16-17). These are the virtues to which Aristotle pointed to when speaking to his students. On the other hand, the moral virtues, such as self-control and generosity, are formed through habit beginning at a very early age. The moral virtues are dispositions such that no set of examples or reasons given could ever determinately define the virtues, which for Aristotle defined the act of teaching. They may provide prototypical examples for some general types of circumstances, but most situations are actually different from each other in such ways that seeing how the circumstances matter in each case is of more practical importance than knowing the general examples of virtue. Thus, it is over the long term of life experience and through continuous reflection on the specifics of one’s practical experiences that one may develop a disposition in a way that connects to a practical/moral virtue. One might be aided by examples early on, but to know about such examples will not come close to producing the dispositions to act the right way through all the different circumstances we face. Since moral wisdom has no clear first principles and reason giving is not necessary, Aristotle argues that it cannot be taught. Moral wisdom must be acquired through acting and evaluating the results of our actions in every single circumstance of our lives and over a lifetime (Of course this Dispositions 19 Aristotelian notion can also be criticized as a kind of self-surveillance of which Foucault [1991] critiqued, though Aristotle seeks to follow the virtue ethic desire for wisdom, which is often uncertain and frail, while the discourse of professionalism is based upon a desire for certainty, efficiency and measurability). These dispositions are developed early and are difficult to excise and replace with others. They are part of the inculcation process rather than the teaching process that takes place in later years. Simply, a disposition cannot be taught in a manner that can be measured as successful or not. I quote at length Aristotle’s explanation of this condition: Now if discourses on ethics were sufficient in themselves to make men virtuous, ‘large fees and many’ . . . ‘would they win’, quite rightly, and to provide such discourses would be all that is wanted. But as it is, we see that although theories have power to stimulate and encourage generous youths, and, given an inborn nobility of character and a genuine love of what is noble, can make them susceptible to the influence of virtue, yet they are powerless to stimulate the mass of mankind to moral nobility. For it is the nature of the many to be amenable to fear but not to a sense of honour, and to abstain from evil not because of its baseness but because of the penalties it entails; since, living as they do by passion, they pursue the pleasures akin to their nature, and the things that will procure those pleasures, and avoid the opposite pains, but have not even a notion of what is noble and truly pleasant, having never tasted true pleasure. What theory then can reform the natures of mean like these? To dislodge by argument habits long firmly rooted in their characters is difficult if not impossible. We may doubtless think ourselves fortunate if we attain some measure of virtue when all the things believed to make men virtuous are Dispositions 20 ours . . . . Again, theory and teaching are not, I fear, equally efficacious in all cases: the soil must have been previously tilled if it is to foster the seed, the mind of the pupil must have been prepared by the cultivation of habits, so as to like and dislike aright. For he that lives at the dictates of passion will not hear nor understand the reasoning of one who tries to dissuade him; but if so, how can you change his mind by argument? (NE, Bk. 10, 6-7: Rackham translation). Aristotle’s words are directed to students he assumes have already acquired a taste for virtues, who already are beyond the early dispositions of inculcation, and who have settled into good habits. Aristotle’s students are prepared to deepen and contemplate the intellectual virtues in relation to the moral virtues. Each type of virtue is dispositional, with the intellectual in line with philosophical deliberation, which is also a practice (Burnyeat 1980). Aristotle’s students, akin to college students of the modern era, have already been inculcated into particular dispositions and character traits, ones that suit the life of an intellectual. Only those who have been fully prepared through childhood inculcation, according to any generalizable virtue ethic, are prepared to deliberate upon virtues and possibly revise actions based upon what Aristotle called the proper combination of reason and desire. If a student comes with what Aristotle deems dispositions that are based upon fear and passions (those aspects of human nature upon which codes of ethics regulates) rather than love of virtue, then no amount of argument or demonstration will have an affect. To put this idea another way: Some dispositions that are determinate can be easily demonstrated and so observable and testable in a short period of time, if you will; such as the disposition to blush when a profanity is uttered. Another dispositional example would be a teacher reacting with rage when a student becomes disrespectful. Simple codes of Dispositions 21 ethics (e.g. one does not verbally or physically abuse a student) are able to explain and control this circumstance. This kind of disposition can be demonstrated or taught, which according to Aristotle, is the business of demonstrating or giving reasons and explanations. One can easily and quickly identify the change in color of an individual’s face when he or she hears the joke or when he or she feels anger swelling up inside due to a student’s behavior. The terms become descriptive. However, how does one demonstrate the virtue and, so, dispositions of justice, or even social justice, another complicated term that has entered into mainstream vocabulary and has taken on some fascinating material conditions? A child could sit in a country or state criminal courtroom all day long, but did he or she learn anything about justice? The child observes specific instances upon which the possibility of drawing an inference may one day coalesce with many other experiences and translate into an understanding of justice, but nothing of the particular event can be explained as justice. Most likely, the child learned more about how handcuffs and chains work and the color differences that exist between lawyers, judge and alleged criminal. Or, how can one demonstrate charitableness? Pincoffs (1986) provides this example to illustrate the difficulty, even impossibility, of such direct instruction. I can stand before students and give them a definition, show them a film and test them on whether they can rehearse the abstract theories of charity transmitted to them. I can even take them outside to a homeless shelter and pick a homeless person to give money to. Or to employ the hands on approach, have each student go and donate money. However, is that charity? Does one watching such activity learn what charity is? According to Aristotle’s logic, an individual cannot learn such dispositions, which tend to be the ones society values the most. One has to literally embody them by performing a charitable act over and over again throughout life, coming, in adulthood, to understand this virtue to the Dispositions 22 point that he or she is truly disposed toward acting virtuously out of the love of the virtue itself. Again, habit is a key term because often dispositions are equated with habits of action, which is not actually accurate (Pincoffs 1986). An individual may over time be taught the technical habit of opening a door for another individual, but this in itself is not a disposition. In other words, the act of opening doors for others is not a quality that one would necessarily say is a requirement for being the right sort of individual for this or that position. It only indicates what one did in this or that particular circumstance. Nothing is said about the overall character of that individual. The act of a man opening the door for a woman or vice versa could be viewed as little more than the beginning act of seduction or an ingrained social etiquette that has lost its cultural purpose and meaning. However, as Pincoffs (1986) points out, to say that someone is polite is to go well beyond the particular circumstance of opening the door and to the overall quality of the individual. The one act may bring the observation from another that the person was polite. But it cannot in good faith bring on the observation that the person, therefore, must be a polite person overall. The same goes for calling one professional. To decide that politeness is the right sort of disposition for an individual who is becoming a teacher to possess is one thing, but then to decide one specific strategy by which to teach the individual how to be that disposition is quite another. Whereas in one sense dispositions can be brought up to students as abstract principles to be thought about while experiencing ethical situations, the problem lies in the desire to assess whether students have “learned” or embodied the meanings of those dispositions in a way that they act upon them in life. This would lead to direct moral training and enforcement, despite the understanding that dispositions are not learned in such a direct fashion. Dispositions 23 Conclusion: The study of, but not assessment of To engage in the study, rather than the transmission, of dispositions, as operating from Aristotle’s notion of intellectual excellence and practical reasoning, occurs with those who have passed through a good portion of life and have experiences from which to draw when discussing the possible meanings, values and complexities of such dispositions. In the context of virtue ethics, the best one can do at the college level is to address and theorize (theoria) the intellectual and moral dispositions. If students are receptive, meaning if they come equipped with certain dispositional desires and habits that support receptivity, reason giving and deliberation in an effort to harmonize reason and desire can come about over a long period of time. However, by the time college students are designated teacher candidates, transmission and assessment of dispositions are misguided and too late, unless one takes the position that college students are still children, and that colleges of education will have access to them for more than two to four years; or, that the dispositions NCATE officials actually seek are the traditional professionalized ones, which are already firmly entrenched by years of schooling. Or, one could take the position that all teacher candidates must spend two years in the field, under probationary status, in which they are observed and dialogued with on a daily basis, in and out of school. Then at the end of two years – an arbitrary number -- it is judged whether the teacher candidate has settled into the dispositions deemed appropriate for one who teaches. Within the current context of teacher education and the overall political environment, that is a highly doubtful scenario. This is not to assert that teacher education faculty should disregard the notion of dispositions just because the dispositions and virtues that NCATE states are valuable, such as caring, responsibility and social justice, cannot be assessed according to the criteria framed within the historical context of professionalization. The problem is in the Dispositions 24 attempt to assess a pre-service teacher’s disposition in action, so to speak. To attempt to make such an assessment creates the scenario in which an observer would be forced to accept the notion that the virtues and dispositions have universal characteristics that can be identified in any given situation and hence can be framed within some sort of rubric (the catch-word for assessment minded educational reformers), to be checked off. This is to believe that dispositions and virtues such as responsibility and fairness can be defined and refined to control every contingency in a schoolroom. There is nothing effective teacher research can do to prove that a particular act of fairness, or the occasional necessity for unfairness, will correlate with an act of learning. However, as a professor, I can certainly judge if a pre-service teacher is aware of what dispositions are, how they operate in virtue ethics and how they might play out in individual’s actions in the world. I can judge this awareness through dialogue, by having them read research, perform research, write and present on virtue ethic issues. Such and intellectual engagement could possibly result in a pre-service teacher participating in theoria. The hope – not a term of measurement and assessment, but one that certainly is more accurate to what actually occurs – is that the pre-service teacher eventually chooses to possess the desire to operate out of praxis, a kind of thoughtful action that emerges from years of study and experience. Over time, and dependent upon a lifelong interest in such philosophical issues, an individual may possibly come to ethical conclusions to alter his or her dispositions because of a love for particular virtues and act in accordance with them. If I visit that preservice teacher many years down the road and spend a good deal of time with him or her, I might be able to make such a judgment as to whether this internalization has taken place and if the individual is still concerned and thinking about such matters. But I cannot judge Dispositions 25 whether pre-service teachers have internalized particular dispositions, at least if one follows the logic set forth in Aristotle’s version of virtue ethics. References: Abbot, A. 1988. The System of Professions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Aristotle. 1962. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated with Introduction by Martin Ostwald. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. Aristotle. 1999. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Bauman, Z. 1993. Post-modern Ethics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Press. Bowers, C.A. and Flinders, D. 1990. Responsive Teaching: An Ecological Approach to Classroom Patterns of Language, Culture, and Thought. Columbia: Teachers College Press. Broadie, S. 1991. Ethics with Aristotle. New York: Oxford University Press. Burbules, N and Densmore, K. 1991. “The limits of making teaching a profession.” Educational Policy, 5 (1): 44-63 Burnyeat, M.F. 1980. “Aristotle on learning to be good.” In Essays on Aristotle Ethics, Edited by Amelie Oksenberg Rorty. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 69-92. Carnegie Task Force on Teaching as a Profession. 1986. A National Prepared: Teachers for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy. Cherryholmes, C. 1988. Power and Criticism: Poststructural Investigations in Education. Columbia: Teachers College Press. Collinson, V., Killeavy, M., and Stephenson, H. 1999. “Exemplary Teachers: Practicing Ethic of Care in England, Ireland, and the United States.” Journal for a Just and Caring Education, 5 (4): 340-366. Dispositions 26 Collinson, V. 1996. “Becoming an Exemplary Teacher: Integrating Profession, Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Knowledge.” (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. ED 401 227). Coulter, D. and Orme, L. 2000. “Teacher professionalism: The wrong conversation.” Education Canada, 40 (1): 4-7. Darling-Hammond, L. N.D. “Solving the dilemmas of teacher supply, demand, and standards: How we can ensure a competent, caring, and qualified teacher for every child.” New York: National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future. Darling-Hammond, L. 2002.”Research and rhetoric on teacher certification: A response to ‘Teacher Certification Reconsidered’." Education Policy Analysis Archives, 10(36). Retrieved [date] from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v10n36.html. Darling-Hammond, L. 1992. “Teaching and knowledge: Policy issues posed by alternate certification for teachers.” In The Alternative Certification of Teachers. Edited by D. Hawley. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teacher Education. Demmon-Berger, D.1986. Effective Teaching: Observations from Research (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. ED 274 087). Doll, W. 1998. “Curriculum and Concepts of Control.” In Curriculum: Toward New Identities. Edited by William F. Pinar. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 295-324. Educational Testing Service. 2000. Wenglinsky, H. How Teaching Matters. Princeton, NJ. Feistritzer, E. 1999. “The making of a teacher: A report on teacher preparation in the United States.” Washington, D.C.: The Center for Education Information. Foucault, M. 1991. "Governmentality." In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Edited by Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon and Peter Miller. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Fuller, E. 1999. Does teacher certification matter? A comparison of elementary TAAS performance in 1997 between schools with high and low percentages of certified teachers. Unpublished report. Charles A. Dana Center, Austin: University of Texas. Gitlin, A. 1996. “Gender and professionalization: An institutional analysis of teacher education and unionism at the turn of the twentieth century.” Teachers College Record, 97, (4): 588-624. Gitomer, D. and Latham, A. 1999. The Academic Quality of Prospective Teachers: The Impact of Admissions and Licensure Testing. Educational Testing Service. Princeton, NJ. Hargreaves, A., Earl, L. and Schmidt, M. 2002. “Perspectives on Alternative Assessment Reform.” American Educational Research Journal, 39 (1): 69-100. Dispositions 27 Huebner, D. 1998. The Lure of the Transcendent: Collected Essays by Dwayne E. Huebner. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. INTASC, 1992. “Model Standards for Beginning Teacher Licensing and Development: A Resource for State Dialogue.” Washington, D.C.: Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium. Judd, C. 1929. “Teachers colleges as centers for progressive education,” National Education Association Addresses and Proceedings, 67: 31-37. Katz, L. 1993. “Dispositions: definitions and implications for early childhood practices. Urbana, Ill.: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education. Kraft, N. 2001. “Standards in teacher education: A critical analysis of NCATE, INTASC and NBPTS.” Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, Seattle, WA. Labaree, D. 1992. “Power, knowledge, and the rationalization of teaching: a genealogy of the movement to professionalize teaching.” Harvard Educational Review, 62, (2): 123-154. McKeon, Richard. Ed. 1966. The Basic Works of Aristotle. New York: Random House. McKnight, D. In press. Schooling, the Puritan Imperative, and the Molding of an American National Identity: Education’s “Errand into the Wilderness.” Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Morgan, J. 1988. Godly Learning: Puritan Attitudes Toward Reason, Learning, Education, 1560-1640. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press. National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). 2001a. At www.ncate.org/resources/assess_examples_broch. National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). 2001b. At www.ncate.org/newsbrf/dec report. National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). 2001 edition. Professional Standards for the Accreditation of Schools, Colleges, and Departments of Education, Glossary section. Washington, D.C. National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). 2002 edition. Professional Standards for the Accreditation of Schools, Colleges, and Departments of Education, Glossary section. Washington, D.C. National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future. 1996. “ What matters most: teaching for America’s future” New York, NY. No author. National Education Association. N.D. Code of Ethics. At www.nea.org/aboutnea/code. Dispositions 28 National Research Council. 1999. How People Learn: Bridging Research and Practice Edited by Donovan, M.S., Bransford, J.D., and Pellegrino, J.W.. National Academy Press. Washington, DC. Percey, R. 1990. “The effects of teacher effectiveness training on the attitudes and behaviors of classroom teachers.” Educational Research Quarterly, 14,(1):15-20. Pincoffs, E. 1986. Quandaries and Virtues: Against Reductivism in Ethics. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. Powers, S. 1999. Transmission of Teacher Dispositions: A New Use for Electronic Dialogue. Eric Document Reproduction Service, No. ED 432 307. Rivkin, S., Hanushek, E. & Kain, J. 1998. Teachers, Schools and Academic Achievement. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper No. 6691. Schon, D. 1987. “Educating the Reflective Practitioner.” Address to the American Educational Research Association, Washington, DC. Stahlhut, R. and Hawkes, R. 1994. “Human relations training for student teachers.” ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 366 561. Sanders, W., & Rivers, J. 1996. “Cumulative and residual effects of teachers on future academic achievement.” University of Tennessee Value–Added Research and Assessment Center. Slavin, R. 2002. “Evidence-based Education Policies: Transforming Educational Practice and Research.” Educational Researcher, 31 (7): 15-21. White, D. (April, 1969). “Education in the turn-of-the-century city: The search for control.” Urban Education, 4 (1): 169-182. Tyack, D. and Hansot, E. 1982. Managers of Virtue: Public School Leaders in America: 1820-1980. New York: Basic Books. Wiebe, R. 1967. The Search for Order. New York: Hill and Wang. Wise, A. 2001. “Performance-Based Accreditation: Reform in Acton.” Editorial. At http://www.ncate.org/newsbrfs/reforminaction.htm. Wise, A. 1999. “Effective teachers…or warm bodies.” Washington, DC: National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. At http://www.ncate.org. Yinger, R. and Hendricks-Lee, M. 2000. The Language of Standards and Teacher Education Reform. Educational Policy, 14, (1): 94-107. Zeichner, K. 1991. Contradictions and tensions in the professionalization of teaching and the democratization of schools. Teachers College Record, 92 (3): 363-380.