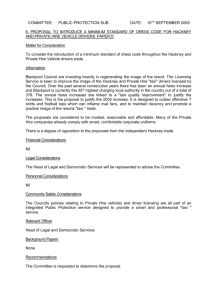

Taxi Industry Inquiry - Interim Report

advertisement