click - Tests & Test

advertisement

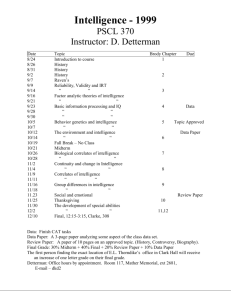

Paper presented at the First Annual South Padre Island Conference on Cognitive Assessment of Children and Youth in School and Clinical Settings November 26 & 27, 1993 A Compendium of Proceedings, p. 35-49 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A Nonverbal Alternative to the Wechsler Scales: The Snijders-Oomen Nonverbal Intelligence Tests Dr. Peter Tellegen Summary The Snijders-Oomen Nonverbal Intelligence Tests are instruments that can be individually administered to children for diagnostic purposes. The tests make a broad assessment of a spectrum of intelligence functions possible without being dependent upon language skills. Because the tests can be administered without the use of written or oral language, they are suitable for use with children who are handicapped in the areas of communication and language development. For the same reason, they are also suitable for use with immigrant and bilingual children who do not have a good command of the language used by the examiner. In this paper the test contents of the latest revision of the test for the younger children will be described (SON-R 2.5-7, to be published in 1994), and the results of some small scale studies into the relationship of the revision of the test for older children (SON-R 5.5-17) with other intelligence measures. Special attention is given to aspects of administration which make the tests child-friendly and more suited to children we become easily demotivated. Introduction Their dependency on language skills in test contents and instructions makes the Wechsler scales less appropriate for the assessment of cognitive abilities of ethnic minorities and of children with problems with verbal communication, such as deaf and hearing disabled children and children with speech and language disorders. For these groups, low performance on a general intelligence test like the WPPSI and the WISC might primarily reflect poor verbal knowledge and/or little experience with the English language instead of limited reasoning and learning ability. This does not imply that administration of the Wechsler tests to these children would not provide valuable information. However, one should be aware of the dangers in interpreting these scores as measures of overall intelligence. Also when the interpretation is restricted to the Performance Scale, these objections are not fully overcome. The instructions of the Performance part are given verbally and may be less well understood by the particular groups mentioned above. Moreover, the subtests in this part load strongly on the Perceptual dimension and are less focused on abstract reasoning abilities. Nonverbal alternatives for intelligence assessment like Raven's Progressive Matrices (Raven, Court & Raven, 1983) and the Test Of Nonverbal Intelligence (TONI-2; Brown, Sherbenou & Johnson, 1990) have the drawback that they are unidimensional tests which do not allow for generalizations to a broad area of intelligence. In 1943 a nonverbal test series intended for deaf children was published by Mrs. Nan Snijders-Oomen (Snijders-Oomen, 1943). This test, known as the SON test, included nonverbal subtests related to abstract and concrete reasoning. In subsequent revisions the test was standardized both for hearing and deaf children. The latest revision for children from 5 to 17 years appeared in 1989 (SON-R 5.5-17; Snijders, Tellegen & Laros, 1989); a new revision for the younger children (the SON-R 2.5-7) will be published by the end of 1994. These individually administered tests examine a broad spectrum of intelligence without being dependent on language. Although the construction of norms has until now remained constricted to the Netherlands, manuals and scoring forms have always been translated into English and German and research results with the tests with various groups of children have been published in many countries. For instance, with deaf and hearing disabled children (Backer, 1966; Stachyra, 1971; Balkay & Engelmayer, 1974; Watts, 1979; Schaukowitsch, 1981; Zwiebel & Mertens, 1985), children with speech and language disorders (Grimm, 1987), children with learning disabilities and mentally retarded children (Sarimsky, 1982; Schmitz, 1985; Eunicke-Morell, 1989), autistic children (Steinhausen, Goebel, Breinlinger & Wohlleben, 1986; SüssBurghart, 1993), motor handicapped children (Colin, Frischmann-Rosner, Liard & Magne, 1974; Constantin, 1975), children from ethnic minority groups (de Vries & Bunjes, 1989; Eldering & Vedder, 1992), normal children (Malhotra, 1972; Harris, 1979, 1982; Ditton, 1983; Melchers, 1986 ; Wolf, 1991; van Aken, 1992) and psychiatric patients (Plaum, 1975; Plaum & Duhm, 1985). Detailed information on the construction, the administration, the reliability and the validity of the SON-R 5.5-17 can be found in the manual (Snijders, Tellegen & Laros, 1989) and in the dissertation by Laros & Tellegen (1991). A summary was recently published in the European Journal of Psychological Assessment (Tellegen & Laros, 1993). In this paper we will focus on a description of the revised SON-R 2.5-7 and we will give a summary of some small-scale studies, performed by other researchers, into the relationship of the SON-R 5.5-17 with other intelligence tests. The SON-R 2.5-7 The last revision of the Pre-school-SON took place in 1975 (Snijders-Oomen, 1976). After such a period of time a revision is needed because the norms and the data concerning reliability and validity are subject to obsolescence. An important goal of the revision was to make the test more suitable for the youngest and the oldest age groups by enlarging the item set with very easy and with more difficult items. This resulted in almost a doubling of the number of items. However by skipping items at the beginning of the subtests for older or more able children and by discontinuation after, at the most, three errors, the total testing time required is about an hour on the average. In the composition of the SON-R 2.5-7 we have tried to connect the test with the SON-R 5.517. For this purpose, a number of subtests have been developed that appear in both tests. The easiest items in the subtests of the SON-R 5.5-17 are the basis for the most difficult items in the comparable subtests of the SON-R 2.5-7. Therefore, it seems plausible that both tests measure intelligence in the same manner for the overlapping age range (Tellegen, Wijnberg, Laros, Winkel, 1992). In the following a short description of each subtest will be given. The subtests in the SON-R 2.5-7 are: 1. Mosaics, 2. Categories, 3. Puzzles, 4. Analogies, 5. Situations and 6. Patterns. The six subtests are composed of 14 to 17 items that increase in level of difficulty. The subtests each have two parts. These two parts differ in materials and instruction. In the first part examples are incorporated in the items; the second part of each subtest is preceded by an example and the remaining items are solved by the subject independently. Mosaics Mosaics consists of 15 items and 1 example item. In part I the child is required to copy different simple mosaic patterns in a frame using three to five red squares. The difficulty is determined by the number of squares to be used and whether or not the examiner first demonstrates the item. In part II diverse mosaic patterns are copied in a frame using red, yellow and red/yellow squares. Each mosaic pattern consists of 9 squares; that correspond to the parts of the pattern. In the easiest items of part II only red and yellow squares are used, and the pattern is printed in the actual size. In the most difficult items all of the squares are used and the pattern is scaled down. The squares are 32 mm by 32 mm and are printed with the same colors on both sides. Categories Categories consists of 15 items and 1 example item. In part I four to six cards must be sorted into the correct category. In the first few items the drawings on the cards belonging to one category strongly resemble each other. For example, a shoe shown in different positions. In the last items of part I the concept lying behind the category must be understood in order to complete the item successfully. For example, vehicles that have a motor contrasting with those that do not. Part II is multiple choice. In this part the child sees three pictures of objects that have something in common. Two pictures that have the same thing in common have to be chosen from another column of five pictures. The level of difficulty is determined by the amount of abstraction in the characteristic. Puzzles Puzzles consists of 14 items and 1 example item. In part I puzzles must be laid in a frame to resemble the given example. These puzzles each have three pieces. The first few puzzles are first demonstrated by the examiner. The most difficult puzzles in part I have to be independently solved. In part II a whole must be formed from 3 to 6 puzzle pieces. No instructions are given as to what the puzzles should represent; the frame is no longer used. The number of puzzle pieces partially determines the level of difficulty. Analogies Analogies consists of 17 items and 1 example item. Analogies is the only subtest in which two different test booklets are used for parts I and II. In Analogies I the child is required to sort blocks into two boxes on the basis of either form, color, size, or a combination of the three. The child must discover the sorting principle him or herself. In the first few items the blocks to be sorted are generally the same as the ones pictured in the test booklet. In the last items of part I the child must discover the principle independently. For example large versus small blocks. Analogies II is multiple choice. Each item consists of an example analogy in which a geometric figure changes in one or more aspects to form another geometric figure. The examiner demonstrates a similar change. The same principle is used. The examiner and child together choose the correct alternative from a number of possibilities. Following this the child has to apply the same change to another figure and choose the correct alternative independently. The child must point to the correct alternative. The level of difficulty in the items is related to the number and complexity of the transformations. Situations Situation consists of 14 items and 1 example item. Part I consists of items in which 4 pictures are shown in the booklet with half of each picture missing. The child has to place the halves in the correct picture. The first item is printed in color in order to make the principle clear. The level of difficulty is determined by the amount of similarity between the different halves belonging to an item. Part II is multiple choice. Each item consists of a drawn situation from which one or more pieces are missing. The correct piece (or pieces) must be chosen from a number of alternatives in order to make the situation logically consistent. Patterns Patterns consists of 16 items. The child is required to copy an example pattern using a pencil. The first items are drawn freely, then dots have to be connected in order to make the pattern resemble the example. The first few items are first demonstrated by the examiner and consist of not more than 5 dots. The last items consist of 9 or 16 dots and are to be directly (and independently) copied by the child. Four types of subtests have always been represented in the SON-tests: abstract reasoning tests, concrete reasoning tests, spatial tests and memory tests. In the composition of the SONR 5.5-17 this was changed: a test for memory was not included in the test series. The authors of the test consider research on memory to be a separate field that no longer fits within the margins of intelligence testing (Snijders, Tellegen & Laros, 1988, p.20). For the same reason no memory test has been included in the present revision of the Pre-School-SON. Tests of reasoning generally form the core of most intelligence tests. They can be divided into abstract and concrete reasoning tests. Abstract reasoning tests (Categories and Analogies) depend on relations between concepts that are abstract, namely, not bound to time or space. A principle for ordering must be derived from the test materials that has to be applied to new materials. Concrete reasoning tests (Puzzles and Situations) refer to persons or objects that are bound together by space and time. The accent can be placed on the either the spatial or the time dimension, this leads to different types of tests. The SON-R 2.5-7 only includes tests in which the spatial dimension is emphasized. Spatial tests (Mosaics and Patterns) resemble concrete reasoning tests in that by both a relationship must be seen within a spatial whole. In concrete reasoning tests the emphasis lies on conceiving meaningful relations between parts of a picture, in spatial tests on form relations between parts of a figure. The instructions to the test can be given verbally or in a nonverbal way by gestures or by a combination of both. An important aspect of the instructions is demonstration by the examiner. Care has been taken not to give extra information in the verbal instruction by naming objects or concepts. This flexibility in the way the instructions are given allows for a natural and stimulating contact. The communication can be adapted to the normal ways of interacting with a particular child. Another important aspect of administering the test is that feedback is given after each item. In the SON-R 5.5-17 this feedback is limited to telling the child whether the answer is correct or incorrect. In the SON-R 2.5-7 the correct solution is always demonstrated to the child by the examiner. If possible, just a little help will be given so the child can complete the item by him or herself. This feedback also allows for a more natural interaction between examiner and the child and it gives the child a better understanding of the requirements of the task in case the instructions have not been fully understood. In this respect there is a close resemblance between the SON tests and tests based on the ideas of Learning Potential Assessment (Tellegen & Laros, 1993). Test norms will be based on a stratified sample of 1100 children (eleven half-year groups from two years and three months up to seven years and three months. This standardization research was performed in the second half of 1993. Data on the reliability and factorial structure will be available later this year. Extensive research is being performed for the validation of the tests. This includes the relationship with other intelligence measures and tests on language development, memory and perception and research with special groups of children for whom the test seems especially appropriate. Among these groups are children with hearing-, speech- and language disorders, deaf children, children with learning problems, autistic children, and immigrant children for whom Dutch is often second language. An extensive account of this research, which will be performed partly in Australia and the USA, will be published in the manual. The SON-R 5.5-17 In this section the results of three small-scale studies into the relationship of the SON-R with other intelligence tests will be summarized. They were performed by other researchers after the publication of the SON-R 5.5-17. Relation with WISC-R and Raven Progressive Matrices (Nieuwenhuys, 1991) A group of 35 children from an outdoor psychiatric university clinic were tested with the SON-R, the WISC-R and the Raven Progressive Matrices Test. The age range was from 6 to 16 years and there were no immigrant children in the sample. The WISC-R (Van der Steene et al, 1991) has recently been standardized for the Dutch population. For the Raven (Raven, Court & Raven, 1983) English norms were used; eight groups of percentile scores were transformed to standard scores. Administration of the SON-R and the WISC-R was alternated within a period of two weeks. The Raven was generally combined with one of the other tests. For the SON-R the standard IQ was used. In the following table the means and standard deviations, and the correlations between the IQ scores are presented. Table 1. A comparison of SON-R 5.5-17, WISC-R and Raven Progressive Matrices ___________________________________________________________________________ correlations -------------------------------------------VIQ PIQ FSIQ Raven SON-R mean sd --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------VIQ .65 .55 .66 95.5 13.9 WISC-R PIQ .65 .74 .80 96.8 17.8 FSIQ .71 .80 95.6 15.9 Raven Prog. Matrices .55 .74 .71 - .74 96.1 11.4 SON-R 5.5-17 .66 .80 .80 .74 97.8 15.8 __________________________________________________________________________ There is a great similarity in the means of the IQ scores. Paired t-tests showed no significant differences between the means. Also the standard deviation of the WISC FSIQ was equal to standard deviation of SON-R IQ. The standard deviation of the Raven was substantially lower but the norms of that test are not comparable. There are substantial high correlations of .80 between the SON-R IQ and the WISC-R FSIQ and PIQ. The correlations of the SON-R IQ and the PIQ with the verbal scale of the WISC-R are about the same (.66 and .65) and both scores correlate .74 with the Raven. Compared to the Raven, the SON-R shows higher correlations with all the IQ scores of the WISC-R. Relation of SON-R with four WISC-R verbal scales (Jansen, 1991) Fourteen children from 6 to 12 years, who had been diagnosed as having specific language impairment at a center for speech and language disorders, were re-assessed after several years with four verbal tests from the WISC-R and with the SON-R. For these children there still existed a large discrepancy between verbal intelligence as measured by the WISC-R VIQ (mean = 83.1; sd = 14.8) and nonverbal intelligence as measured with the SON-R (mean = 97.5; sd = 14.0). The difference was significant at the .01 level. In this particular group the correlation of the SON-R IQ with the VIQ was moderate, r=.35, and not significant. Relation of SON-R with LEM (Veerman, 1993) At a school for deaf children a comparison was made between the performance of 14 children (age-range 5 to 7 years) on the SON-R and on an adapted version of the Learning test for Ethnic Minorities (Hessels & Hamers, 1993). The LEM is a nonverbal test, based on theories of learning potential assessment, in which help is given to the subject during administration. The means and standard deviations were very similar for the SON-R (mean = 101.3; sd = 21.2) and the LEM (mean = 101.4; sd = 20.6). The correlation between the standardized total scores was high (r=.86). The SON-R correlated .70 with teacher's assessment of intelligence on a three-point scale; the LEM .63. Discussion For those situations in which intelligence assessment is required by means of a test battery which is not dependent on specific language skills, the SON tests seem to be a good, and maybe the only, sensible alternative. Nonverbal tests like the Raven and TONI-2 cannot be considered as alternatives either for the Wechsler scales or for the SON tests because they are so much limited in contents and do not allow for generalizations to a broad area of intelligence. This is illustrated by the higher correlations of the SON-R with the WISC-R compared to the Raven. Another question might be whether the performance part of the Wechsler tests could not be used as a substitute for a nonverbal test. However, they use verbal instructions and they seem more limited in contents compared to the SON tests. Although we would expect the correlation of the SON-R with the WISC-R VIQ to be higher compared to the correlation between PIQ and VIQ this was not the case in the research by Nieuwenhuys. Two factors may have contributed to a relative underestimation of the correlation of the SON-R with both the VIQ and PIQ. Because administration of the complete WISC was done in one session (with verbal and performance subtests alternated) and the administration of the SON-R took place some weeks earlier or later, any order effects of testing and day to day variations in motivation, concentration, well being and, as a result, in performance will have had adverse effects on the correlation of the SON-R with the VIQ but not on the correlation of the PIQ with the VIQ. For a better comparison also the verbal and the performance part of the WISC should be separated in time. An important difference between the SON-tests and other nonverbal intelligence tests is the flexibility in the use of language and gestures in giving the instructions. For instance with the UNIT (Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test), a nonverbal test series that is being developed by Bracken & McCallum, no verbal communication is allowed during the administration of the subtests and there are strict rules for the gestures that are allowed. Although the flexibility that is allowed with the SON tests might make these tests less standardized, we expect that a more natural communication with the child will contribute to the validity of the results. Too strong an emphasis on the objectivity of administrative rules can have undesirable effects on the motivation of the subjects and on the comprehension of the tasks. The way feedback is given to the children with the SON-R 2.5-7 also contributes to a natural and cooperative interaction between the examiner and the child. Moreover, because the subtests are discontinued after three errors in total, feelings of failure will not so easily arise as with the Wechsler tests which generally require five consecutive errors. All these factors make the test pleasant to do, not only for most children but also for the examiner. For this reason the SON tests are not only useful instruments for children with problems in the area of language and communication, but for all children, and especially the young ones, for whom motivation is of prime importance for valid assessment and diagnostic purposes. References Aken, M.A.G. van (1992). Die Entwicklung der allgemeinen Kompetenz und bereichsspezifischer Kompetenzen [The development of general competence and domainspecific competencies]. European Journal of Personality, 6, 267-282. Backer, W. (1966). Tests of intelligence for children with impaired hearing. Journal for social research, 15, 11-27. Balkay, S.B. & Engelmayer, A.L. (1974). [The application of Raven's Coloured Matrices Test in examining the hearing defective]. Magyar Pszichologiai Szemle, 31, 202-216. Brown, Sherbenou & Johnson, (1990). Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, second edition. Austin, Texas: Pro-ed. Colin, D., Frischmann-Rosner, M., Liard, J. & Magne, A. (1974). [Study of the level of global mental development and of perceptual, memory and reasoning capacities through the use of the Snijders-Oomen Performance Scale with motor handicapped children]. Bulletin de Psychologie, 27, 346-361. Constantin, F. (1975). Die visuelle Wahrnehmung und Visuomotorik bei Kindern mit leichten zerebralen Bewegungsstörungen. Salzburg: Universität, Philosophische Fakultät. Ditton, H. (1985). Ein Modell zur Prognose sprachlicher Fähigkeiten von Kindern im Schuleintrittsalter [A model for the prediction of verbal ability in preschool age children]. Zeitschrift für Empirische Pädagogik, 7, 123-134. Eldering, L. & Vedder, P. (1992). Opstap: Een opstap naar meer schoolsucces? [Opstap: a start for more success at school?]. Amsterdam/Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. Eunicke-Morell, C. (1989). Untersuchung zum Zusammenhang von Motorik und Intelligenz. Theoretische und methodologische Aspekte [Study on the relationship between psychomotor development and intelligence. Theoretical and methodological aspects]. Motorik, 12, 57-65. Grimm, H. (1987). Entwicklung der Dysphasie: Neue theoretische Perspektiven und empirische Befunde [Developmental dysphasia: New perspectives and empirical results]. The German Journal of Psychology, 11, 8-22. Harris, S.H. (1979). An evaluation of the Snijders-Oomen non-verbal intelligence scale (SON -7). Dissertation Abstracts International, 40, 2840. Harris, S.H. (1982). An evaluation of the Snijders-Oomen Nonverbal Intelligence Scale for Young Children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 7, 239-251. Hessels, M.G.P. & Hamers, J.H.M. (1993). A Learning Potential Test for Ethnic Minorities. In J.H. Hamers, K. Sijtsma & A.J.J.M. Ruijssenaars (Eds.), Learning Potential Assessment, Theoretical, Methodological and Practical Issues. Amsterdam/Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. Jansen, B. (1991). Een exploratief onderzoek naar de werkbaarheid van een diagnose: Hoe specifiek is de diagnose "Specifieke Taalontwikkelingsstoornis"? [An exploratative study into the usefullness of a diagnosis]. Groningen: Internal report, Academic Hospital. Laros, J.A. & Tellegen, P.J. (1991). Construction and validation of the SONSnijders-Oomen non-verbal intelligence test.Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. -17, the Malhotra, M.K. (1972). [On the validity of Snijders-Oomen's nonverbal intelligence test series]. Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie, 19, 122-129. Melchers, P. (1986). Erprobung der Kaufman-Assessment Battery for Children an deutschen Kindern: Validität [Validity of the German version of the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children]. Köln: Universität, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät. Nieuwenhuys, M. (1991). Een vergelijkingsonderzoek SON-R, WISC-R en Raven-SPM. [A comparative study of SON-R, WISC-R and Raven-SPM]. Amsterdam: Internal report, Department of Developmental Psychology. Plaum, E. (1975). Ein multivariater Ansatz zur Untersuchung kognitiver Störungen bei Schizophrenen. Göttingen: Universität, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät. Plaum, E. & Duhm, E. (1985). Kognitive Störungen bei endogenen Psychosen [Cognitive disorders in dogenous psychoses]. Psychiatrie, Neurologie und medizinische Psychologie, 37, 22-29. Raven, J.C., Court, J.H. & Raven, J. (1983). Manual for Raven's Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. London: H.K. Lewis & Co Ltd. Sarimsky, K. (1982). Effects of etiology and cognitive ability on observational learning of retarded children. International Journal of Rehabilitation research, 5, 75-78. Schaukowitsch, E. (1981). Ein Vergleich der Intelligenz hörender und tauber Kinder mit der Snijders-Oomen nicht-verbalen Intelligenztestreihe [The intelligence of hearing and deaf children assesses by means of the "Snijders-Oomen Nonverbal Intelligence Scale"]. Wien: Universität, Grund- und Integrativwissenschaftliche Fakultät. Schmitz, G. (1985). Anforderungsanalyse - Diagnostik - Training im Rahmen handlungspsychologischer Ansätze in der beruflichen Rehabilitation. [Action-psychological approaches to vocational rehabilitation]. In: Berufsverband Deutscher Psychologen. Psychologische Hilfen für Behinderte. Beiträge vom 11. BDP-Kongress für Angewandte Psychologie 1981. Band 1: Grundprobleme. Weinsberg: Weissenhof-Verlag. Snijders-Oomen, N. (1943). Intelligentieonderzoek van doofstomme kinderen [The examination of intelligence with deaf-mute children]. Nijmegen: Berkhout. Snijders, J.Th. & Snijders-Oomen, N. (1976). Snijders-Oomen Non-verbal Intelligence Scale SON 2.5-7. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Snijders, J.Th., Tellegen, P.J. & Laros, J.A. (1989). Snijders-Oomen non-verbal intelligence test: SON-R 5.5-17. Manual and research report. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Stachyra, J. (1971). [The mental development of deaf children]. Roczniki Filozoficzne, 19, 101-114. Steinhausen, H.C., Goebel, D., Breinlinger, M. & Wohlleben, B. (1986). Eine gemeinbezogene Erfassung des infantilen Autismus [A community survey of infantile autism]. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 186-189. Süss-Burghart, H. (1993). Die "Münchener Funktionelle Entwicklungsdiagnostik 2/3" bei mental retardierten Kindern und im Vergleich mit Intelligenztests. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 14, 67-73. Tellegen, P.J. & Laros, J.A. (1993). The Snijders-Oomen Nonverbal Intelligence Tests: General Intelligence Tests or Tests for Learning Potential? In J.H. Hamers, K. Sijtsma & A.J.J.M. Ruijssenaars (Eds.), Learning Potential Assessment, Theoretical, Methodological and Practical Issues. Amsterdam/Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. Tellegen, P.J. & Laros, J.A. (1993). The Construction and Validation of a Nonverbal Test of Intelligence: The Revision of the Snijders-Oomen Tests. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, Vol 9, Issue 2, 147-157. Tellegen, P.J., Wijnberg, B.J., Laros, J.A. & Winkel, M. (1992). Evaluatie van de SON 2.5-7 ten behoeve van de revisie -7 for the revision. Groningen: Internal report, Department of Personality Psychology, HB-92-1058-EX. Veerman, M.J. (1993). Een vergelijkend onderzoek van de SON-R en de LEM bij dove kinderen [A comparative study of the SON-R and the LEM with deaf children]. Utrecht: Internal report, Department of Orthopedagogiek. Vries, A.K. de & Bunjes, L.A. (1989). Zwakke rekenprestaties bij buitenlandse adoptiekinderen in de basisschool [Mathematical disorders in adopted children from foreign countries]. Kind en Adolescent, 10, 165-174. Watts, W.J. (1979). The influence of language on the development of quantitative, spatial and social thinking in deaf children. American Annals of the Deaf, 124, 46-56. Wechsler, D. (1974). Wechsler Intelligence Scale For Children - Revised. New York: The Psychological Corporation. Wechsler, D. (1990). Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence - Revised. Manual. Sidcup, Kent: The Psychological Corporation. Wolf, B. (1991). Hohes Strukturenähnlichkeit bei Testwiederholing trotz niedriger EinzelRetest-Korrelationen. In Reinhold, J.S. 20 Jahre Zentrum für empirische pädagogische Forschung. Geschichte, aktuelle Forschung und künftige Entwicklung (p.91-97). Landau: Universität Koblenz-Landau, Zentrum für empirische pädagogische Forschung. Zwiebel, A. & Mertens, D.M. (1985). A comparison of intellectual structure in deaf and hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf, 130, 27-31.