Arthur Schopenhauer`s definition of concept spheres, judgement

advertisement

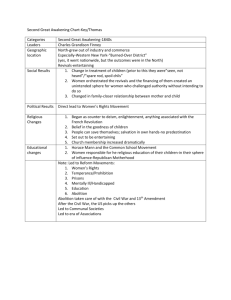

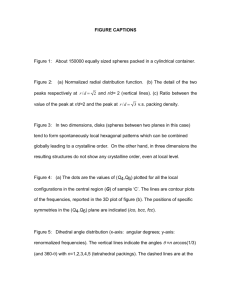

Arthur Schopenhauer's definitions of concept spheres, judgement and the art of persuasion. From The World as Will and Representation. Volumes I & II. [E]very concept, just because it is abstract representation, not representation of perception, and therefore not a completely definite representation, has what is called a range, an extension, or a sphere, even in the case where only a single real object corresponding to it exists. We usually find that the sphere of any concept has something in common with the spheres of others, that is to say, partly the same thing is thought in it which is thought in those others, and conversely in those others again partly the same thing is thought which is thought in the first concept; although, if they are really different concepts, each, or at any rate one of the two, contains something the other does not. In this relation every subject stands to its predicate. To recognize this relation means to judge. (I 42) It has been shown that concepts borrow their material from knowledge of perception, and that therefore the whole structure of our world of thought rests on the world of perceptions.[…] Mere concepts of a thing without perception give a merely general knowledge of it. We have a thorough understanding of things and their relations only in so far as we are capable of representing them to ourselves in purely distinct perceptions without the aid of words. To explain words by words, to compare concepts with concepts, in which most philosophizing consists, is at bottom playing with concept-spheres and shifting them about, in order to see which goes into the other and which does not. At best, we shall in this way arrive at conclusions; but even conclusions by no means give new knowledge. On the contrary they only show us all that lay in the knowledge already existing, and what part of this might perhaps be applicable to each particular case. On the other hand, to perceive, to allow the things themselves to speak to us, to apprehend and grasp new relations between them, and then to precipitate and deposit all this into concepts, in order to possess it with certainty; this is what gives us new knowledge. But whereas almost everyone is capable of comparing concepts with concepts, to compare concepts with perceptions is a gift of the select few [this is the power of judgement]. (II 71-72) Correct and exact conclusions are reached by our accurately observing the relation of the concept-spheres, and admitting that one sphere is wholly contained in a third only when a sphere is completely contained in another, which other is in turn wholly contained in the third. On the other hand, the art of persuasion depends on our subjecting the relations of the concept-spheres to a superficial consideration only, and then determining these only from one point of view, and in accordance with our intentions, mainly in the following way. If the sphere of a concept under consideration lies only partly in another sphere, and partly also in quite a different sphere, we declare it to be entirely in the first sphere or entirely in the second, according to our intentions. […] The sphere of a concept is almost invariably shared by several others, each of which contains a part of the province of the first sphere, while itself including something more besides. Of these latter concept-spheres we allow only that sphere to be elucidated under which we wish to subsume the first concept, leaving the rest unobserved, or keeping them concealed. [The accompanying diagram] shows how the concept spheres in many ways overlap one another, and thus enable us freely to pass arbitrarily from each concept to others in one direction or another. [Travelling] overlaps into the province of four others, to each of which the persuasive talker can pass at will. These again overlap into other spheres, several of them into two or more simultaneously; and through these the persuasive talker takes whichever way he likes, always as if it were the only way, and then ultimately arrives at good or evil, according to what his intention was. In going from one sphere to another, it is only necessary always to maintain direction from the center (the given chief concept) to the circumference, and not go backwards. The manner of clothing such a sophistication in words can be continuous speech or even the strict syllogistic form, as the hearer's weak side may suggest. (I 48-49)