Political Obligation - Flinders University

advertisement

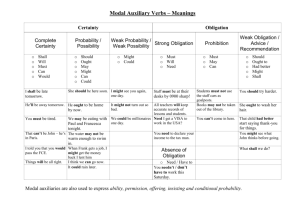

The Political Obligations of Corporations: Justifying A Role for the State in Enforcing Accountability Carol A. Tilt* and Gillian S.F. Lubansky** * Lecturer in Accounting, School of Commerce, Flinders University, South Australia ** Tutor in Philosophy, School of Philosophy, La Trobe University, Victoria Correspondence should be addressed to: Dr Carol A. Tilt School of Commerce Flinders University GPO Box 2100 Adelaide SA 5001 Ph (08) 8201 3892 Fax: (08) 8201 2644 Email: Carol.Tilt@flinders.edu.au The authors wish to thank Laurence Lester and Nicholas Mangos for their helpful comments. All errors are the responsibility of the authors. Accountability and Corporations’ Political Obligation: Justifying A Role for the State in Enforcing the Social Contract Abstract Many papers written about social and environmental accounting and reporting discuss the accountability aspect of public disclosure. Within these discussions there is an implicit assumption that there exists a social contract between society and business. Some papers explicitly acknowledge its existence, but few attempt to investigate the notion in any detail. Those that do, appear to rely on a change occurring in the attitude of corporations to the social environment. This paper considers this unlikely, and that the state must play a role in ensuring the accountability of organisations. It examines corporations’ political obligation and where it lies, relying on the notion of fairness. The paper supports the case for requiring the state to regulate social reporting. It concludes that arguments for greater corporate disclosure based on duties or rights may be stronger if they are used justify the political obligation of corporations to obey the state, rather than waiting for a change in corporate conscience. Keywords: Political Obligation; Fairness Theory; Social Contract; Social and Environmental Accounting; The State. 1 Introduction Over ten years ago, Gray et al. (1988) provided the first paper where accountability and the social contract were investigated as part of a theory for corporate social reporting (CSR). Since then, many papers have implicitly and explicitly acknowledged the existence of a contract between society and business, but do little more than use its presence as justification for social reporting without reference to its complexities or its history (see, for example, Heard & Bolce, 1981). Given that work on the subject of social contracts has been published since the 1700s, this can only be seen as cursory attention. Yet, social contract arguments have been central to the tradition of social change and reform (Donaldson, 1982). As acknowledged by Deegan (1998) however, many papers use the notion of the social contract as part of other theories, eg. legitimacy theory, where “…there is a ‘social contract’ between the organisation and those affected by the organisation’s operations” and which may be revoked if they operate outside the terms of the contract (Deegan, 1998, p. 17). A major criticism of the early work undertaken in developing a theory for CSR has been that the state’s role has been ignored (Gray et al, 1988; Lehman & Tinker, 1997) or it is assumed that the state “…pursues a neutral, mediating role in conflict resolution” (Tinker, 1991, p. 29). Most alternative approaches, such as those encouraging ‘participatory democracy’ (Lehman, 1995, 1996), suggest some form of mandated disclosure or reporting by corporations, imposed by the state, for the benefit of the rest of the community. That is, enforcing the social contract as opposed to being left to market forces. What is not considered however, is the accountability or obligation that arises from this, and why corporations (or other institutions for that matter) should be so obliged to provide such information. The concern of this paper is twofold. First, the paper considers the state’s role in enforcing social accountability. It advances the notion raised by Lehman and Tinker (1997, p. 10) that “within middle of the road liberalism, itself, there exists justifications for the state to move beyond its [current] remit”. Second, the paper considers the political obligation that necessarily underlies state regulation, and uses fairness theory to justify such obligation. 2 There have been some notable attempts to elaborate on the notion of social accountability in the literature. Lehman (1995) uses Rawls’ theory of justice to examine and support the concepts of accountability and transparency in environmental reporting (considered to be a sub-set of social reporting). He discusses the “social and moral obligations” (p. 394) of organisations to provide an account of their activities, and that “accountants have a duty” (p. 403) to provide such an account. While this paper has no argument with Lehman’s (1995) ideals, it questions whether such a duty will ever be recognised and acted upon without coercion. Similarly, other researchers discuss reasons that corporations ‘should’ account for their actions based on ‘moral’, ‘ethical’ or ‘fair’ grounds (Gray, 1992), but do not consider how we ensure the ‘should’ becomes ‘does’. This paper takes the position that while the desirability of accounting for social and environmental activities of organisations is undisputed, the means to ensure provision of that account must lie (at least in part) with the state. That is, regulation or legislation is necessary to force organisations to report as a first step towards achieving social accountability. A justification for the adherence of organisations to such regulations can then be based on the notion of political obligation (as opposed to simple obedience) along similar lines to those presented by Lehman (1995). In this paper an argument based on fairness theory is presented. The paper outlines how such actions by the state can be seen as being within the state’s current functions, and why coercion by the state is justified. The paper is structured as follows. The next section discusses the state as it is defined in this paper and an examination of its role in enforcing social accountability. This is followed by a general discussion of the literature on political obligation and details of fairness theory that is drawn upon in this paper. Finally the theory is applied in a discussion of the emergence and enforcement of social and environmental accounting practices. The State To talk of a ‘state’ is to use a shorthand term for a way of thinking about the political relations between members of a community. The state is an independent political community; a rule- 3 governed association of people occupying a defined territory and organised under a sovereign government - that is, one that has supreme civil power and authority. A sovereign state is one that exercises authority as a matter of right over all persons within that state and that has no authority competent to override it within its territory. Furthermore, if there should be conflict between individual citizens and the state, the state as sovereign would prevail in that conflict. Not every political entity we call a state has full sovereignty. States within a federation or commonwealth1 surrender part of their sovereignty to the federal state. Reference to ‘state’ in this paper is to sovereign states. There are certain features of a state that distinguish it from other associations (Benn & Peters, 1959): 1. A state claims compulsory jurisdiction over all those within its territorial boundaries and those legal boundaries can also include external territories. It claims universal jurisdiction over those within the boundaries, whether they are members of that state, that is, citizens, or resident aliens or merely visitors. Its rules take precedence over any other rules applying within its borders, such as those laid down by the church, for example. Associations other than the state have limited power and areas of influence. The state, by contrast, has a substantial amount of power and the potential to interfere in the lives of its residents. 2. The state’s primary functions are to keep order, maintain internal security and protect itself from external threats. It also provides public goods for those living in its territory. One thing that distinguishes states from other forms of association is that the scope of the state’s functions is indeterminate. 3. The method by which a state carries out its primary functions is through the use of law supported by coercive powers. Although most associations can apply sanctions when their rules have been broken, these are only enforceable if the state permits them to be so enforced. Only the state has the right to give this permission since it has a monopoly on the legitimate use of coercion. 1 As in the Commonwealth of Australia, not the British Commonwealth. 4 Liberal Democracy The discussion in this paper is concerned only with Western liberal states. Such states have the following features: they are pluralist, multi-party, representative democracies, in which governments are elected for limited terms by universal franchise. The famous four freedoms of thought, speech, conscience and of the press - are officially endorsed, as is the freedom to do what one wills unless and until it is restricted by law. These states have a primarily capitalist mode of production, in which the motivation for production is profit, and the means are privately owned. However, there are notable areas in which the state intervenes, such as health, welfare and education, and, to some extent, in the marketplace itself (Linley, 1986). It has been observed that “Western liberal states are in fact liberal democracies, combining principles of individual liberty with principles of collective self-government and egalitarianism” (Barber, 1985, p. 55). However, ‘liberal democracies’, as many people have claimed, are neither fully liberal nor fully democratic. The democratic ideal, of maximum participation of all citizens, is in direct contrast to the liberal ideal, which has at its heart an ideal of freedom to pursue one’s own ends. Liberals focus on the freedom of the individual to choose their own road, consistent with the freedom of others. That is, one has the right to do as one wishes subject to the constraint that one may not infringe on the rights of others. The salient point to note is that it is the individual who takes primacy over the group. The view of classic liberal theory holds that political liberty is concerned with the restriction of the power of the government, not merely with restraints imposed either through lack of capacity, means or opportunity. The state, in the purest form of liberalism, is not permitted to encroach on the citizens’ activities except to preserve their freedom. If there were such a thing as a purely liberal state, it would act as an arbitrator and watchdog. It should be strictly neutral when dealing with the citizens, so that the processes used in so dealing with conflicts between citizens would not favour any one interest, but instead would facilitate the maximisation of each citizen’s freedom. Liberal democratic states generally have a representative democratic system. Democratic systems of government try to ensure political equality through universal suffrage and equality 5 of opportunity in influencing political leaders. Western liberal democracies are not democracies in the classical sense in which all citizens make all the decisions because the growth of large, more impersonal states made this impossible. Representative democracies are a compromise in which ordinary citizens have access to the political domain by choosing their representative. The representative votes in parliament, not as the citizen tells him or her to, but as though he or she had a mandate to act as the citizens might have chosen to. Pateman (1979) suggests that in fact the only democratic element in modern states is universal adult suffrage, enabling all adults to at least vote for a representative. The problem for liberal democracies is that the more democratic they get, the less liberal they are likely to be - and vice versa. In spite of this problem, a liberal democratic system is argued to be better than any other political system because it better promotes people’s individual rights. One justification for the state is that it enhances the freedom of each individual in the context of the constraints forced upon people through living in a society. It is most likely that liberal democratic states will have demonstrable political obligation. This is so because the liberal aspect of the political system tries to ensure people’s individual rights and freedom, and permits them to make their own decisions. At the same time, the democratic aspect, in theory, ensures that people have adequate representation in the policy making of their state. The citizens of a liberal democratic state, including corporate citizens (see discussion later), are to a large extent both the beneficiaries and the initiators of rule in those states, and their political obligation, if any, will be derived from their involvement in the activities of the state. The state will function most effectively when citizens accede to its demands. One important political obligation is the obligation to help to maintain the state which, for most citizens, is generally done by obeying the law. Green (1988, p. 5) suggests that “…a state is legitimate only if, all things considered, its rule is morally justified”. Where such rule is not morally justified, there can be no political obligation. To say that a state is legitimate is to say both that the state functions according to accepted rules - accepted, that is, by those who are to obey them - and that the state’s use of power is justified in that it supports and fulfils the political desires and values of the people within that state. 6 Political Obligation This paper views political obligation as obligation that arises from participation within the political areas of life, as will be discussed below. It might be thought that political obligation creates legal obligation, but this is not the case. To have a legal obligation is to be constrained to comply with those rules established by the law-making body within a particular political community, just because they are so established. One can have legal obligations without having political obligations, but if one has political obligations then one automatically has legal obligations as part of that political obligation. Many of the demands our political community makes of us are couched in terms of obeying the law, and doing so is assumed to be a demonstration of our acceptance of our political obligations. A citizen is a member of a political community, unlike someone, such as a resident alien, who is merely subject to its control. The following discussion assumes that if anyone can be held to have political obligation, it will be those people who are citizens of a state. In fact, part of the concept of political obligation is that it applies primarily to those people who are full members of their political community2, including corporations as will be discussed later. Asking the ordinary person if we have any obligation to the state may elicit two different replies. One is a reply focussing on obedience for purely practical reasons such as security or fear of sanctions, and this reply may be given by both citizens and resident aliens. The other reply concerns the special relationship that they believe citizens have with the state that stands apart from the practical questions of community living. This paper is not concerned with the prudential reply. Its concern is whether there is a special relationship between citizen and state, whether there are any obligations attached to citizenship, and the philosophical explication for that obligation. 2 In the Lockean sense, which requires active commitment to the state (see Locke, 1952, section 119). 7 Justifying Political Obligation Modern liberal democratic theory holds all citizens to be political and legal equals. The state, as the embodiment of the political community, is an entity that organises and administers community systems; arbitrates to resolve conflict, both civil and criminal; carries out programs to achieve social justice and other welfare, health and education programs; and provides essential goods and services such as roads, defence, and so on. Many people believe that part of the state’s role is to ensure the provision of these goods and services. That most modern states do so is obvious. This does not refer to any specific state, but to modern states that profess to be liberal democracies, since there are sufficient similarities among them that these remarks will apply to them all in broad outline. The question is whether the provision of these goods and services gives the state the right to any relationship with its citizens apart from its role as adjudicator and protector. To many the primary purpose of the state is its maintenance and the concomitant provision of goods and services. Since this is the case, there are good reasons for thinking that it is fair to ensure that all contribute to the provision of those goods and services. This is particularly so since those goods and services include such things as the protection of law and government, which are available to all. The point is whether the state’s provision of goods and services is sufficient return to the citizen for the costs inherent in the restriction of autonomy and foregone enjoyment. The relationship of citizens with the state is a reciprocating one, in which both state and citizens make demands on each other. Citizens expect that the state will provide, or at least facilitate the provision of, certain goods and services. Some, such as welfare, health services or education, could be provided by private contractors to those who can afford to pay for them. More difficult to provide privately are public goods, such as defence, policing, clean air or unpolluted water. 8 The Role of the State in Social Accounting Gray (1992) discusses the need for organisations to become transparent and accountable and provide an array of arguments in support of this claim. Lehman (1995) asserts that a “...moral obligation exists to provide additional environmental information in published accounting reports” (p. 393) but says that this “...is not a call for more information and more regulation” (p. 408). He suggests that inclusion of environmental information in annual reports is fair and just and therefore ‘should’ be done. Lehman admits that his argument “...does not imply that justice will prevail over powerful interest groups”, but states that failure to account will mean an “...individual’s life goals will not be attainable” leaving their life “empty and vain” (Lehman, 1995, p. 408). Such emotional predictions seem somewhat at odds with the assumption that regulation is not necessary – implying that corporations might suddenly find a social conscience that has hitherto gone unnoticed. Lehman (1995, p. 405) does, however, consider the possibility that we may wish to “revise the law” by perhaps including a refined version of Gray et al.’s (1987, 1991) compliance with statute approach. A possibility supported in this paper. Similarly, Donaldson (1982) suggests that if corporations do not fulfill the terms of the social contract and enhance the welfare of society, they will receive moral condemnation from society. This may be so, but moral condemnation may not be enough of a threat to cause them to reform their activities. The only way to ensure that the terms of a social contract are met is to have those terms enforced. Such enforcement can only be provided by the state. One of the state’s major roles, as discussed above, is to maintain the continuation of the state – this is paramount to the argument that the planet must be protected or the state cannot continue to exist. Additionally, the state must act it own best interest rather than be manipulated by powerful subsets of the state. Self (1985, p. 187) asserts that an “important index to the welfare of any society is the quality and safety of its ‘public domain’ – the streets, parks, community buildings, etc. which provide the meeting places for a vital common life”. It is not difficult to expand this list to include areas of the natural environment, and to suggest 9 that prevention of manipulation by ‘corporate’ citizens (certainly a powerful sub-set) is in the interest of the remaining citizens. Fairness theory (as discussed below) suggests that those who benefit more should bear more of the burden (thus the argument in favour of a progressive tax regime, (see Lubansky, 1994)). Corporations are high earners, often at the expense of the environment, and thus should bear more of the burden for protecting it. Similarly, they must provide greater amounts of information to facilitate the fair flow of information between parties that make up the venture (Ijiri, 1983; Pallot, 1991). As suggested by Pallot (1991) “greater accountability is the quid pro quo for greater power or control over resources...”. Thus, the obvious role for the state is to enact environmental protection laws in order to maintain the existence of the planet. The recent increase in environmental protection legislation provides evidence that this role has been accepted. However, a less obvious but equally important role of the state is to ensure adherence to those laws – most easily through compliance checks – ie. accounting or reporting. Lehman (1995, p. 408) summarises his essay on environmental accounting as identifying the “...obligations of corporations to provide an account of their actions”. This paper suggests that this argument would be better utilised to support the ‘political obligation’ that corporations have to adhere to, and report on, mandatory environmental regulations developed by the state. The next section briefly discusses some of the theories that have been offered to justify political obligation, of which there are many. Since subsequently this paper concentrates on one theory that gives the most plausible grounds for political obligation, provided here is an overview of the most common ones with only brief comments regarding their adequacy. Fairness Theory and Political Obligation Implicit in this paper is the notion that the corporation is a citizen, as is an individual. Although the literature on liberal democracies discussed above refers only to people, corporations are separate legal entities and their power means they generally have more 10 influence than any individual citizen on the activities of the state, and are able to choose more easily whether to accept their obligations. Although corporations cannot vote, their influence is certainly felt in the political arena, and they affect the lives and welfare of many people (Donaldson, 1982; Miller and Ahrens, 1988). Further discussion of the legitimacy of discussing the corporation in the same terms as an individual citizen is beyond the scope of this paper, however, it remains an important area for future debate. Theories justifying the political obligation of citizens of a state abound. Examples are those based on gratitude (Simmons, 1987), the general will (Rousseau, 1968), and utilitarianism (Bentham, 1967). The theory of political obligation that this paper considers however, is based on the principle of fairness, and is a variant of the social contract theory, which is: ...a theory in which a contract is used to justify and/or set limits to political authority, or in other words, in which political obligation is analysed as a contractual obligation (Lessnoff, 1986, p. 2). The original work on the principle of fairness carried out by Hart (1955) has been extended and modified by Rawls (1972). Rawls’ (1972, p. 112) version states that: The main idea is that when a number of persons engage in a mutually advantageous cooperative venture according to rules, and thus restrict their liberty in ways necessary to yield advantages for all, those who have submitted to these restrictions have a right to a similar acquiescence on the part of those who have benefited from their submission. Once a member participates in the scheme, that member has the obligation to submit to the rules of the group and is consequently entitled to the submission of the other members. The major distinction between the two versions is that Hart (1955, pg183) explicitly says, in his version of the principle, that those in authority are permitted to coerce members of the community into complying, while Rawls prefers to rely on justice, which he sees as integral to his principle. The principle of fairness as a ground of political obligation says that people have political obligations on the basis of their involvement in a mutually beneficial scheme. It is clearly a 11 version of the social contract theory, because it requires participation by both parties to the contract. One party is the state, which, as the result of the joint enterprise set up by the potential citizens, provides certain benefits. The receipt of those benefits generates political obligation on the part of the members of that scheme, who in this case are the citizens, on the basis that it is only fair that those who receive, should in turn give. This paper asserts that although there are many objections to it, it is the account of the ground of political obligation most likely to succeed. One objection to the theory is based on the problem common to all social contract theories, which is that few, if any, citizens actually make the requisite commitment. Other objections centre on the difficulties of explaining how receipt of benefits by those who have not made any commitment can be held to create obligations but this can be met by using a theory of justice (such as Rawls’) to support the principle of fairness. The objections can be met by examination of the value, not just economic, of the proposed benefits. In this way, the principle of fairness as a ground for political obligation can be used successfully to explain, at least to a limited extent, how those who choose not to cooperate can also be held to have obligations. It seems that the principle of fairness cannot be used to explain the ordinary person’s obligation unless he or she has decided to participate in the joint enterprises that constitute the state, which would seem to reduce it to a consent theory. People do not decide to participate in the state, but Klosko (1987, 1992) suggests a way to explain how people can be obligated to participate even where they have not intentionally elected to take part in a scheme. In Klosko’s (1987, p. 37) words: the principle of fairness can be used most plausibly to establish political obligations by appealing to society’s provision of important public goods. He thinks that those who live in a state have a special relationship with, implying obligations to, their fellow citizens and consequently the state, whether or not they are actually aware of it. Although they may live in and be given benefits by the state without any actual commitment on their part, they are still to be regarded as having acquired obligations by virtue 12 of the receipt of those benefits, particularly those that he calls ‘presumptively beneficial public goods’. The problem for Klosko’s claim is that people are not ordinarily obligated by receipt of benefits unless they are free to choose whether to accept or reject them, as Nozick (1974) is at pains to point out. His response is that the principle of fairness can ground certain limited cases of political obligation, which will include those who have not consciously joined any co-operative scheme in the way that is suggested by both the Hart (1955) and the Rawls (1972) formulations. While it is, he says, unfair that anyone should benefit without contributing, obligations can be imposed if the person “…must unavoidably profit from the efforts of others” and the goods cannot be provided without the participation of others (Klosko, 1987, p. 35). Those who choose not to participate can only do so fairly if they are able to avoid the goods being offered, which must be presumptively beneficial.3 Otherwise, the non-cooperator must take on their share of the burden. The reasons for this are derived from the principle of fairness’ reciprocity claims. That is, as Klosko (1987, p. 34) puts it, “the moral basis of the principle of fairness is the mutuality of restrictions”. The principle of fairness says, “those who have submitted to those restrictions have a right to a similar acquiescence on the part of those who have benefited from their submission” (Rawls, 1972, p. 112). That is, if you benefit, others have a right to your equal submission, and, according to Hart (1955), may coerce you to do so. This means that in spite of apparent non-involvement, people can be held, based on the principle of fairness, to be bound to contribute to the provision of certain benefits because of the intrinsic value of those benefits, and so be forced to contribute. Klosko presents a case for the application of the principle of fairness in which he claims that people are obliged to obey the state because the state provides benefits that cannot be rejected by the recipient. Underlying his claim that the principle of fairness can justify political 3 A presumptively beneficial good is one that one is rationally presumed to want, and hence one that one would hypothetically consent to producing. 13 obligation through the provision of presumptively beneficial goods are three basic, and he says, uncontroversial assumptions. They are (Klosko, 1987, p. 40): 1. There are certain public goods without which people could not live. 2. Government provides at least one of the public goods noted in (1.). 3. As a rule, there are no other presumptive public goods that are provided to the inhabitants of a given territory that are not provided by government. In relating these justifications to the point being made in this paper, people cannot live without a relatively clean environment, thus it is certainly a ‘presumptive public good’. Similarly, a scheme to protect the environment certainly provides benefits to all members of the state (ie. members of society). Finally, only the state has the power to ensure a clean environment (corporations could do it but do not necessarily have a strong motive to do so and it is often in conflict with their goals of increasing profit or share price). The difficult step in this argument is the one that justifies some form of accounting or reporting by corporations about their environmental activities. The theory of social contract analyses political obligation as a contractual obligation (Lessnoff, 1986), thus, in order to ensure adherence to the contract, some form of reporting or information provision must be included, hence the argument for reporting legislation in addition to environmental protection legislation. Just as Lehman (1995) asserts that accounting for the environment may be justified on fairness grounds, so coercion (or regulation) by the state can be similarly justified. Obligation or Obedience? It may appear at times through this paper that it concentrates on political obedience rather than political obligation. The justification of political obligation is an explanation in part of political obedience once the practical aspects of that obedience have been set aside. The establishment of the duty of compliance with the law is one, very important, consequence of justifying political obligation. There are two possible motivations for political obedience. People may choose to obey because of some philosophical motivation, or they may do so because of some instrumental reason for doing so, eg. self-interest. Without an adequate 14 theory of political obligation, we are left only with considerations of self-interest to motivate obedience. While political obedience can be and is enforceable, political obligation is not. One tactic that authorities use to ensure compliance on the part of the citizens is to emphasise the political obligations of those citizens. Conclusions In summary, this paper suggests that although social and environmental accounting can be justified on grounds of moral obligations, fairness or justice, the distribution of power in society allows individual groups (such as corporations) to ignore their obligations without penalty. Thus, only state regulation can achieve the required result. Such environmental regulation is justifiable on grounds of moral obligation and fairness, just as it is possible to demonstrate general political obligations on these grounds (see for example, Lubansky, 1994). Arguments for social accountability based on ‘duty’ or ‘moral obligations’, or the public or community’s ‘rights’ to information can be used to justify regulation and coercion by the state. Likierman & Creasey, (1985, p. 42) state that in the early literature, many considered that “...rights took the place of ordinary and effective legislation”. Similarly, Kant (1781) indicated that a moral duty that is at odds with what we wish to do is the one we are most aware of (Likierman & Creasey, 1985). Likierman and Creasey (1985, p. 44) also point out: One of the major problems of those who assert moral rights is to prove those rights unless they are enshrined in positive rights [recognised by law] and thus enforceable through the courts. While also pointing out objections to this view, they conclude by highlighting the fact that “...claims on moral grounds have often been the forerunner to the establishment of legal rights” (Likierman & Creasey, 1985, p. 48). Using fairness theory, one can justify, for example, the state’s right to enforce payment of taxes. It does not give those liable to taxation the right to withhold payment. Even if one objects to a proposed use for taxation money, one is still required to contribute to the maintenance of the enterprise – the obligation one has to the group remains in spite of that 15 disapproval. Once one is committed, one cannot reject part of that commitment. One can only work to change the way the cooperative venture makes use of tax money from within the system, or withdraw completely from the cooperative venture (Lubansky, 1994). This same argument can be applied to justify the state’s right to restrict the activities of corporations with regard to the social and natural environment and to coerce corporations into reporting on these activities. In essence its role is to enforce the social contract that exists between organisations and society. This paper does not, however, consider that regulation is the single solution to improving the accountability of organisations. It is merely suggesting that such regulation is one front on which the environmental issue must be addressed that provides an active role for the state. A role that helps to ensure that both individual citizen, and corporate citizen, are put on a closer to equal footing when it comes to determining environmental matters. It has been said that fairness theory, while attractive as a ground for political obligation, cannot be used to explain obligation within real states, because real states are not obviously cooperative schemes of the kind on which Klosko and others base their discussion (Simmons, 1987). The objection is that the state, rather than being made up of citizens who together make a corporate body, has a separate existence to those citizens. This seems to be true, but while the government and its attendant bureaucracy may be set apart from the citizens – ‘independent and aloof’, in Simmons’ words - there is a connection between government and citizen via the political processes with which the citizen may be involved. The opportunity to participate in the political process (not just elections) makes the relationship between state and citizen not ‘them and us’, but ‘we’. 16 References Beetham D. 1991 The Legitimation of Power, Humanities Press International, Inc. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey. Barber B. 1989 “Liberal Democracy and the Costs of Consent”, in Rosenblum N.L. (ed) Liberalism and the Moral Life, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass, p. 55. Benn S.I. and R.S. Peters 1959 The Principles of Political Thought, The Free Press, New York. Bentham J. 1967 A Fragment on Government, edited by Harrison W., Blackwell, Oxford. Deegan C. 1998 “Environmental Reporting in Australia: We’re Moving Along the Road, but There’s Still a Long Way to Go”, paper presented at the University of Adelaide/University of South Australia Seminar series, June. Donaldson T. 1982 Corporations and Morality, Prentice Hall, New Jersey. Gray R. 1992 “Accounting and Environmentalism: An Exploration of the Challenge of Gently Accounting for Accountability, Transparency and Sustainability”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(5), pp. 399-425. Gray R., D. Owen, & K. Maunders 1988 “Corporate Social Reporting: Emerging Trends in Accountability and the Social Contract”, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1(1), pp. 6-20. Gray R., D. Owen, & K. Maunders 1991 “Accountability, Corporate Social Reporting, and the External Social Audits”, Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 4, pp. 1-21. Green L. 1988 The Authority of the State, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Hart H.L.A. 1955 “Are There Any Natural Rights?”, Philosophical Review, 64, pp. 175-191. Heard J.E. and W.J. Bolce 1981 “The Political Significance of Corporate Social Reporting in the United States of America”, Accounting, Organizations & Society, 6(3), pp. 247254. Klosko G. 1987 “The Principle of Fairness and Political Obligation”, Ethics, 97, pp. 353-362. Klosko G. 1992 The Principle of Fairness and Political Obligation, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Lanham, Maryland. Lehman G. & Tinker T. 1997 “Environmental Accounting: Accounting as Instrumental or Emancipatory Discourse?”, paper presented at the Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Accounting Conference, Manchester England. Lehman G. 1995 “A Legitimate Concern for Environmental Accounting”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 6(5), pp. 393-412. Lehman G. 1996 “Environmental Accounting: Pollution Permits or Selling the Environment”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 7, pp. 667-676. 17 Lessnoff M. 1986 Social Contract, Macmillan Education Ltd. Likierman A. and P. Creasey 1985 “Objectives and Entitlements to Rights in Government Financial Information”, Financial Accountability and Management, 1(1), pp. 33-50. Linley R. 1986 Autonomy, Macmillan Education, Ltd., Houndmills, and London. Lipset S.M. 1984 “Social Conflict, Legitimacy and Democracy,” in Connolly W (ed) Legitimacy and the State, pp. 88-103. Locke, J. 1952 The Second Treatise of Government The Bobbs-Merril Co, Inc. Indiana Lubansky G. 1994 Political Obligation. A Critique of Some Contemporary Theories, Unpublished Master of Arts Thesis, La Trobe University. Miller Jr. F.D. and J. Ahrens 1988 “The Social Responsibility of Corporations”, in White T.I. 1993 Business Ethics: A Philosophical Reader, Chapter Five, Macmillan, New York Nozick R. 1974 Anarchy, State and Utopia, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Pallot J. 1991 “The Legitimate Concern with Fairness: A Comment”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(2), pp. 201-208. Pateman C. 1979 The Problem of Political Obligation: A Critical Analysis of Liberal Theory, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, New York. Rawls J. 1972 A Theory of Justice, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass. Rousseau J.J. 1968 The Social Contract, Penguin Books Ltd., Middlesex, England. Schaar J.H. 1984 “Legitimacy in the Modern State,” in Connolly W. (ed) Legitimacy and the State. pp. 104-127 Self P. 1985 Political Theories of Modern Government, George Allen and Unwin, London. Simmons A.J. 1987 “The Anarchist Position: A Reply to Klosko and Senor” in Philosophy and Public Affairs, 16(3), p. 273. Tinker A.M., C. Lehman and M. Neimark 1991 “Falling Down the Hole in the Middle of the Road: Political Quietism in Corporate Social Reporting”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 4(2), pp. 28-54. c:\cat\research\in progress\social contract\aos 1999.doc last saved 13-Feb-16 18