Mood and affective problems

advertisement

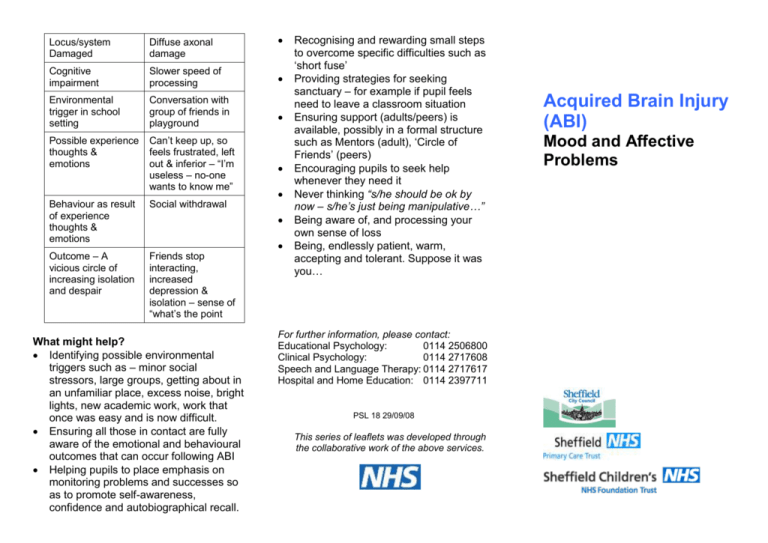

Locus/system Damaged Diffuse axonal damage Cognitive impairment Slower speed of processing Environmental trigger in school setting Conversation with group of friends in playground Possible experience thoughts & emotions Can’t keep up, so feels frustrated, left out & inferior – “I’m useless – no-one wants to know me” Behaviour as result of experience thoughts & emotions Social withdrawal Outcome – A vicious circle of increasing isolation and despair Friends stop interacting, increased depression & isolation – sense of “what’s the point What might help? Identifying possible environmental triggers such as – minor social stressors, large groups, getting about in an unfamiliar place, excess noise, bright lights, new academic work, work that once was easy and is now difficult. Ensuring all those in contact are fully aware of the emotional and behavioural outcomes that can occur following ABI Helping pupils to place emphasis on monitoring problems and successes so as to promote self-awareness, confidence and autobiographical recall. Recognising and rewarding small steps to overcome specific difficulties such as ‘short fuse’ Providing strategies for seeking sanctuary – for example if pupil feels need to leave a classroom situation Ensuring support (adults/peers) is available, possibly in a formal structure such as Mentors (adult), ‘Circle of Friends’ (peers) Encouraging pupils to seek help whenever they need it Never thinking “s/he should be ok by now – s/he’s just being manipulative…” Being aware of, and processing your own sense of loss Being, endlessly patient, warm, accepting and tolerant. Suppose it was you… For further information, please contact: Educational Psychology: 0114 2506800 Clinical Psychology: 0114 2717608 Speech and Language Therapy: 0114 2717617 Hospital and Home Education: 0114 2397711 PSL 18 29/09/08 This series of leaflets was developed through the collaborative work of the above services. Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) Mood and Affective Problems . range of emotional disturbance. Injury to the ventro-medial frontal areas is thought to impact on motivation, as does injury to the right hemisphere and sub cortical damage. It is imperative that this biological underpinning of emotional response is recognised. Difficult behaviours shown by an ABI survivor may look as if they are under his/her control – but may in fact be as far from it as ,say, the ability to walk unaided following nerve damage. Mood and affective problems Following ABI pupils may demonstrate difficulties in “mood and affect” – the way in which they respond emotionally to everyday events. Typically 50-80% of survivors show elements of depression, anxiety, irritability, apathy and indifference. If these emotional consequences of ABI are left unrecognised and untreated there may be long term psychological and social difficulties. Research has shown that families cope much better with the physical disability ABI may have caused than the emotional and behavioural difficulties. This is also likely to be true of peers and school staff: “It’s been two years since the accident – surely it can’t explain why s/he was so rude to Mr Jackson”…. Psychosocial – There are two ways in which ABI impacts on the social life of the pupil . Firstly there is the change in the individuals relationship to others. He/she may be unable to take part in many social activities previously important to them. Peers may drift away; new friendships may be hard to form. At a time when the survivor most needs a supportive social circle and is most vulnerable and damaged, the change in their mood and behaviour may alienate all but the most resilient of their friends and family. This is where the second psychosocial factor lies. Close family and friends are themselves so distressed by the, in effect, ‘loss’ of the pre-injury individual that they struggle to offer the calm, adaptive, problem solving approach essential to aid the emotional recovery of the survivor and may be overwhelmed by their own grief. Environment – Whether at home or at school the pupil is in an environment, both physical and social, and the demands of that environment will interact with the pupil’s vulnerabilities. An example of the way this may happen is as follows: Psychological – How we see ourselves, our self-concept, is central to who we are and how well we function. The pupil who has experienced ABI may find this self perception distressingly threatened in the following ways: Repeated failure and associated frustration Others not believing reports of cognitive difficulties In fact mood and affect disorder may last up to and beyond three years, although for most survivors symptoms generally improve within 3-6 months. In analysing the emotional consequences of ABI it may be helpful to categorise them in three ways: Neurological, Psychological and Psychosocial. same person they were prior to injury. This is hard on the family, and hard on the school, but it may be devastating for the pupil who has sufficient self awareness to recognise how much he/she has changed. Loss of memories Comparison of self pre and post injury Loss of identity through labelling, and fear of stigma Discrepant information from medical services (e.g. being told there is nothing wrong/being given a very poor prognosis) Neurological – The experience and processing of emotions have clear fundamental neurological underpinnings – some of which can be fairly accurately pinpointed in terms of brain structure. For example, injury to the frontotemporal-limbic circuitry leads to a Discrepancy between being ‘normal’ (but not receiving services)and being diagnosed (but being labeled or stigmatised by society) In a nut shell, the pupil who has survived a serious ABI is in very many ways not the .