Syllabus - University of South Alabama

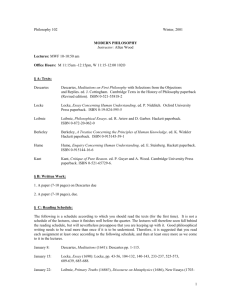

advertisement

1 Phil 245 Renaissance/Enlightenment Philosophy TTH (Time) HUMB ___ Professor: Dr. T. Allan Hillman Office: HUMB 124 Office Hours: TBA Office Phone: 251-460-6842 Email Address: hillman@jaguar1.usouthal.edu Early Modern Philosophy: Survey Course Abstract: Our concern here is an introduction to a few of the predominant themes and figures central to 17th and 18th Century philosophical thought. Constraints on our time being what they are, one has (it seems to me) two options: (1) choose a path broad in scope and cover as much material as possible with the details left to one side, or (2) choose a path more narrow in scope, focusing our attention on select problems, discussing and analyzing these problems in some relative depth. I have chosen option (2) in the hope that, given one’s practice in sustained analysis of certain of the metaphysical and epistemological quandaries in which our Early Modern heroes find themselves, one might not only appreciate the extent to which our intellectual heritage stems largely from some of their more salient positions, but one might also come away from the study having developed the philosophical acumen to pursue those issues not dealt with in our course. As a result, our study will be primarily metaphysical and epistemological – topics including, for instance, the nature of the mind and the body, the existence or non-existence of God, the scope and limits of knowledge, the existence or non-existence of the external world and perceptual theories examining the relation between it and us, and the nature of causal interaction (if any) between individual objects such as bodies and minds. We will concentrate our attention on the works of philosophers from the Rationalist tradition – Rene Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and G.W. Leibniz (squeezing in, if possible, the under-appreciated Malebranche) – as well as philosophers from the Empiricist tradition – John Locke, George Berkeley, and David Hume. Certain other prominent persons, perhaps, may come into the picture as well – e.g., Hobbes, Newton, among others. Of course no Early Modern venture in philosophy would be complete without requisite attention paid to Immanuel Kant, who can be understood as synthesizing in his critical philosophy the (sometimes) disparate strands of the two traditions just mentioned – Rationalism and Empiricism. Course Readings Main textbook: Modern Philosophy: An Anthology of Primary Sources [AW], Roger Ariew, Eric Watkins (eds.), Hackett, 1998. ISBN: 0872204405 Though this will be our primary text, it will occasionally transpire that the readings need appropriate adjustment (read: improvement), and in these instances, I will provide you with a photo-copied handout or some such rendering of the material of interest. Secondary Sources: At the end of the syllabus you will find an attached list of selected secondary texts. These texts are not obligatory but are meant instead as helpful suggestions in the event that you would like to explore a certain topic in more depth, or further pursue a particular question on your own. Of course, they might also be of assistance in certain of the writing assignments with which you’ll be concerning yourself throughout the course. Course Requirements 2 In General: Ho-hum stuff. Individuals who by their actions disrupt the class will be asked to leave. Academic dishonesty on your part will suffice for failure of this course. Any matter not governed by this syllabus is subject to the discretion of the instructor – um, that’s me! Furthermore, the instructor reserves the right to modify the contents of this syllabus at any time. Most importantly, students are responsible for being aware of the requirements and expectations noted in this syllabus, and for any changes to this syllabus that might arise. Attendance: Attendance is required. Some important guidelines: First, note that should you not attend regularly, your quiz and essay grades will almost certainly suffer. That is, they will suffer insofar as much of the material on which you’ll be quizzed and on which you’ll be writing will come from the course lectures. So, it is in your best interest to attend class. Should you not be able to attend for some reason, it is your responsibility to recover the information missed either via your classmates or by a meeting with me during my office hours. Second, absences will be excused so long as you inform me beforehand (i.e. a week before, a day before, an hour before,…) and your excuse for having missed class meets requirements legitimated by the instructor or the university (i.e. illness, family emergency, etc.). Whether an excuse is deemed legitimate will be at the discretion of the instructor. In cases of illness, written documentation from a physician may be requested. Third, for every unexcused absence above five, your final grade will be lowered by one-third of a letter grade. So, suppose that you have six unexcused absences and your final grade dictates an A-: your final grade will then be lowered to a B+. Finally, no make-up quizzes will be administered unless the instructor has been both notified in advance and some form of documentation has been provided to excuse the missing of the quiz. Grading Policy: (1) There will be five in-class quizzes throughout the semester (for the dates of such quizzes, see the Course Schedule below), all weighted equally and amounting in sum to 40% of your grade. Expect the quiz content to be primarily made up of multiple-choice questions, true/false questions, and short-answer questions. (2) There will also be the occasional homework assignment in the form of a written (typed) response to a question I pose in class. In most cases I will simply ask you to analyze a certain bit of the text, present the prevalent argument being advanced, and then criticize and evaluate it (i.e., is it a good argument?). There will be a hard-maximum limit of three-pages and a hard-minimum limit of two pages for these assignments – do not under any circumstances violate this rule (and no fudging about with the fonts or borders). Though I’m not sure at present how many of these there will be (rough estimate of four?), they will in sum amount to about 20% of your grade. (Note: Spelling and grammar count, ladies & gentlemen!) (3) Though there will be no exams in this class, there will be two written (typed) papers, each around 7-8 pages apiece. On these I will suggest a hard-minimum of seven double-spaced pages, though there is no hard-maximum (yet if you start to hedge in the direction of 1215 pages you might need to talk to me about it!). Two weeks before such papers are due, you will be presented with a list of essay questions among which you may choose to answer one of them. (Note: Should a topic arise that you find interesting and, to your anguish, you also find not dealt with in my proposed list of paper topics, by all means talk to me about it – I’m happy to make exceptions in such situations!) Expect the papers 3 collectively to count for the remaining 40% of your grade. (Note: Again, spelling and grammar count!) (4) All students are encouraged to take advantage of my regularly scheduled office hours (or, in cases of conflict, to meet with me by appointment). I also encourage you to contact me via email with specific questions and concerns. Please keep in mind that I am a valuable resource at your disposal, so it is certainly in your best interest to use this resource accordingly. (Note: Feel free as well to stop by my office to chat about pretty much anything relevant to the course or philosophy in general – e.g., if we skip something you find terribly interesting or about which you’re curious, by all means drop in and I’ll be glad to discuss it and/or point you in the direction of some interesting secondary material on it…I can also, without much urging, be finagled into talking about virtually any aspect of the game of football…) Course Schedule T1: Introduction to the Course; some Scholastic Background TH1: Continue the Scholastic Background; Descartes (AW 22-30) T2: Descartes: Methodological Doubt and the Cartesian Project (AW 22-40) TH2: Descartes: Ideas and God (AW 41-55) T3: Descartes: Causation and Dualism (AW 41-55) TH3: Descartes: Dualism (AW 63-81) T4: Spinoza: Cartesian in Spirit? (AW 129-49 esp. Definitions, Axioms, Prop’s 1-14) TH4: Spinoza: Monism (God?) (AW 129-49 cont.) T5: Spinoza: Causation (AW 149-72 esp. Definitions, Axioms, Prop’s 1-19) TH5: Malebranche: Occasionalism (AW 404-12) T6: Leibniz: Individual Substances (AW 184-207 esp. §1-§16 & §26-§30) TH6: Leibniz: Individual Substances (AW 184-207 cont.) T7: Leibniz: Pre-Established Harmony: Criticisms of Descartes & Malebranche (H “De Ipsa Natura”) TH7: Leibniz: Pre-Established Harmony & Leibnizian Causation (AW 214-24) T8: Locke: Lockean Ideas – Primary Quality-Secondary Quality Distinction (AW 270-80, 28490) TH8: Locke: Lockean Essences – Something-I-Know-Not-What (AW 312-20) 4 T9: Locke: A Representative Theory of Perception (AW 285-92) TH9: Berkeley: Criticisms of Locke’s Metaphysics & Epistemology (AW 462-82) T10: Berkeley: Idealism (AW 462-82 cont.) TH10: Berkeley: Idealism & Causation (AW 443-60) T11: Hume: Humean Ideas (AW 491-99) TH11: Hume: Hume on Causation (AW 499-509) T12: Hume: Hume on Causation (AW 514-22) TH12: Kant: What is a Critique of Pure Reason, and Why is it Necessary? (AW 634-41) T13: Kant: A Preface to the Transcendental Deduction (AW 641-53) TH13: Kant: The Transcendental Deduction (AW 653-72) T14: Kant: The Transcendental Deduction (AW 653-72 cont.) TH14: Kant: A Synthesis of Rationalism & Empiricism? (H “Kemp”) List of Secondary Texts (Most assuredly non-exhaustive) On Rene Descartes: Chappell, Vere (ed.). Essays on Early Modern Philosophers: Vol. 1 Parts I & II, Rene Descartes. Garland Publishing, 1992. Cottingham, John (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Descartes. Cambridge University Press, 1992. Dicker, Georges. Descartes: An Analytical and Historical Introduction. Oxford University Press, 1993. Garber, Daniel. Descartes Embodied. Cambridge University Press, 2001. On Baruch Spinoza: Bennett, Jonathan. A Study of Spinoza’s Ethics. Hackett Publishing, 1984. Chappell, Vere (ed.). Essays on Early Modern Philosophers: Vol. 10. Garland Publishing, 1992. Curley, Edwin. Behind the Geometrical Method. Princeton University Press, 1988. Garrett, Don. Cambridge Companion to Spinoza. Cambridge University Press, 1995. On Malebranche: Chappell, Vere (ed.). Essays on Early Modern Philosophers: Vol. 11, Nicholas Malebranche. Garland Publishing, 1992. Nadler, Steven. Cambridge Companion to Malebranche. Cambridge University Press, 2000. Pyle, Andrew. Malebranche. Routledge, 2003. On G.W. Leibniz: 5 Adams, Robert. Leibniz: Determinist, Theist, Idealist. Oxford University Press, 1994. Chappell, Vere (ed.). Essays on Early Modern Philosophers: Vol. 12 Parts I & II, G.W. Leibniz. Garland Publishing, 1992. Jolley, Nicholas (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Leibniz. Cambridge University Press, 2004. Jolley, Nicholas. Leibniz. Routledge, 2005. Mates, Benson. The Philosophy of Leibniz. Oxford University Press, 1986. On John Locke: Ayers, Michael. Locke: Epistemology & Ontology. Routledge, 1993. Chappell, Vere (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge University Press, 1994. Jolley, Nicholas. Locke, His Philosophical Thought. Oxford University Press, 1999. On George Berkeley: Pappas, G.S. Berkeley’s World. Cornell University Press, 2000. Winkler, Kenneth. Berkeley: An Interpretation. Clarendon Press, 1993. Winkler, Kenneth (ed.) Cambridge Companion to Berkeley. Cambridge University Press, 2005. On David Hume: Garrett, Don. Cognition and Commitment in Hume’s Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1996. Norton, David Fate (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Hume. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Stroud, Barry. Hume. Routledge, 1981. On Immanuel Kant: Allison, Henry. Kant’s Transcendental Idealism. Yale University Press, 2004. Gardner, Sebastian. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Kant and The Critique of Pure Reason. Guyer, Paul (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Kant. Cambridge University Press, 1992. On the Early Modern Era in General:*** Atherton, Margaret (ed.). The Empiricists: Critical Essays on Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999. Bennett, Jonathan. Learning from Six Philosophers: Volumes I & II. Oxford University Press, 2001. Cottingham, John. The Rationalists. Oxford University Press, 1988. Garber, Daniel & Michael Ayers (eds.). The Cambridge History of 17th Century Philosophy: Volumes I & II. Cambridge University Press, 2003. Jolley, Nicholas. The Light of the Soul: Theories of Ideas in Leibniz, Malebranche, and Descartes. Clarendon Press, 1998. Nadler, Steven (ed.). Causation in Early Modern Philosophy. Penn State Press, 1993. Pereboom, Derk (ed.) The Rationalists: Critical Essays on Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999. Rutherford, Donald (ed.) Cambridge Companion to Early Modern Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2006. Woolhouse, R.S. The Empiricists. Oxford University Press, 1988. *** There are also many (many!) good collections of essays devoted to each philosopher individually and also to several of these philosophers taken collectively. Should you be interested in finding a few such anthologies of essays, come talk to me! 6 Paper Assignment? In this essay you are to use only the primary text – i.e., Descartes’ Meditation II. No secondary sources are to be used at all (i.e., no internet sites, no books or articles on Cartesian philosophy, etc.). This is an exercise in your critical and analytical reading and writing skills. This essay should be typed and double-spaced, between 3 and 5 pages in length with normal margins and 12-point font (hard maximum of five pages). Of course, grammar, spelling and style are important, though a clear and concise exegesis of the text should be your primary goal. (Hint: focus on the arguments that Descartes provides.) In Meditation II, Descartes finally arrives at something he takes to be known with absolute certainty – a foundational belief upon which any and all other true beliefs may be derived. (1) What is it? (2) How does he claim to know it with such absolute certainty, i.e., how has he reached the conclusion regarding his one absolutely certain belief? (3) After having asserted what Descartes believes this thing to be, describe it for me, i.e., explain to me what it is. Finally, (4) make clear the significance of the “piece of wax” passage near the end of Meditation II. That is, what is it that Descartes wants us to learn about the true nature of the wax and (especially) the perception of its features?