Philosophy - McGill University

advertisement

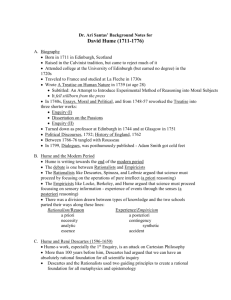

McGILL UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY (2007-08) PHIL 506 Seminar: Philosophy of Mind Mondays: 11:35 a.m. – 1:25 p.m. LEA 927 Prof. J. McGilvray Leacock 925; 398-6053 Office hours: TBA Topic for 2007-08: Contents and theories of mind Two strategies for the study of mind emerged by the end of the 17th century, the empiricist and rationalist. The differences lay in basic assumptions about how to conceive of minds, learning, and a mind’s relationships to what can be loosely conceived as the world. The empiricists such as Locke and, later, Berkeley and Hume, assumed that the mind is at birth what Locke called a “tabula rasa,” and that its ‘contents’ (what gets written on the slate, to continue the metaphor) would have to be learned ‘by experience’. Learning by experience was understood as the application to data (provided by the senses) of some domain-general procedure such as classification of similarities and generalization. Attempts would later be made at specifying the general procedure – association, induction, stimulus-response learning, connectionist statistical algorithms with backprop, etc. However conceived, the result is a picture of the mind that incrementally, through association and correction of error alone, becomes faithful to the data and – through them – the world. Of course, given different environments, one gets different contents and minds. So if there is to be similarity or identity of contents among individual minds, it will depend on similarity or identity of environments. And if one is to study the mind and its contents, one will have to take into account not just the general procedure, but the data received by, and environments of, the individuals involved. Unsurprisingly, some empiricists such as Hume recognized that that overall picture posed some serious skeptical challenges. If access to the world is limited to what minds get through data, no one can claim that their mental contents offer a correct or true representation of the world. To show that they do represent, one would have to have independent, and direct, access to the world. Moreover, he recognized that speaking of similarity and generalization is a dodge: unless one can discover, and specify, the “secret springs and principles” by which all (human) minds receive and characterize data, associate data, and introduce general principles, one has no reason to suppose that one’s mind works the way another’s does. To deal with this fact, Hume in effect shrugged his shoulders: we receive, associate, and introduce “by instinct.” In effect, he assumes that the general procedure is the same in all humans, and is written into (and partially defines) “human nature.” That instinct, he held, is unfortunately “forever hidden” from human view. The rationalists such as Descartes and, later, most of the Port-Royal grammarians, and Leibniz, assumed in contrast that the mind is at birth latently but richly endowed with an innate system or set of systems that – while they require input or experience to activate specific ‘ideas’ – are largely pre-specified within our natures so that they can only assume specific forms. These systems, furthermore, are – with allowances for some differences – generally uniform across the human species. One person’s visual system is – barring differences in cone receptivity ranges, adaptation, fatigue, etc – like another’s. The same is true of ‘higher level’ cognitive systems, including language and the concepts language can assemble into more complex concepts. Uniformity of system does not guarantee uniformity of concepts, of course: different people do have different experiences, and so different concepts are ‘occasioned’. Moreover, there are differences in languages. Nevertheless, the innate system(s) constrain the set of possible concepts and languages. Given this view, it is not surprising that the rationalist simply accepts the fact that we have no guarantee – barring a deus ex machina – that our concepts represent the world ‘as it is’. Nevertheless, skepticism about whether one’s concepts are like another’s is unwarranted, given the assumption that the systems are uniform. We have some reason to think that that assumption is warranted, moreover: not only do we cooperate and communicate with some success, but – far more important – theories of the relevant systems (Hume’s “instincts”) can be and have been successfully constructed. This was true even in Descartes’s time: he developed an early but sophisticated version of a computational theory of vision. Both approaches are found in the practices of contemporary work. The aim of this course is to come to understand the assumptions and views of various rationalist and empiricist efforts to construct theories of the mind. We will also take up the question of which of the approaches to the mind has proven to be more successful. Dealing with that question requires raising the issue of what counts as success in a theory of mind. The format is primarily presentation and discussion. Participants are expected to read and prepare the material(s) assigned each week. Nevertheless, after the first few weeks, we will have no pre-set agenda – no specific set of topics-for-discussion for each week. Specific topics and reading assignments will be announced in class and on WebCT from week to week. Course requirements: In-class presentation (20%) Midterm (take-home essays with assigned questions): 30% Term paper (due last day of classes): 50% Reading materials: Selections from Descartes and Locke (on WebCT) Fodor: Concepts. MIT, 1998 Prinz: Furnishing the Mind: Concepts and Their Perceptual Basis MIT 2002. Selections from various contemporary rationalist and empiricist efforts (on WebCT: Elman, Putnam, Chomsky, etc.)