ASSOCIATION FOR CITIZENSHIP TEACHING

advertisement

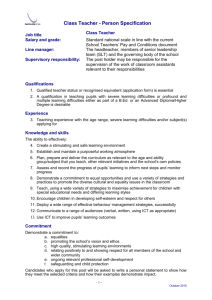

Briefing Paper for Trainee Teachers Of Citizenship Education Citizenship Education and Pupils with Learning Difficulties Produced by citizED (a project of the Teacher Training Agency) AUTUMN 2004 More information about the series of Briefing Papers for Trainee Teachers can be found at www.citized.info Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils Citizenship Education and Pupils with Learning Difficulties pg Contents 1 Key issues and useful links 2 Differentiation in the classroom 3 Citizenship in the school community 4 Citizenship in the community Key Issues Citizenship teachers share the general responsibility of all teachers to understand and implement the principles of inclusive practice. There are a number of general observations to make about this area though, before looking at specific strategies for classroom and community activities. Key Issue 1: Learning from SEN colleagues Aspects of Citizenship education are very closely aligned with established practice in special schools and there is much we can learn from special education colleagues about good inclusive practice. Fergusson and Lawson (2003: Ch.4) advise teachers of pupils with special educational needs that “those who have worked in the citizenship field advocate principles that already hold a high profile within the world of severe and profound and multiple learning difficulties.” These are explored under three broad headings: (i) developing a meaningful sense of community, (ii) developing a pedagogy that is active and child-centred, and (iii) developing structured opportunities for participation. These themes are developed in this briefing paper. Key Issue 2: The PSHE link In KS1&2 Citizenship forms part of a broader programme for Personal, Social and Health Education. This integrated approach reflects the principle that children find it easier to make sense of some of the more complex areas of Citizenship knowledge and understanding when they are embedded in activities that build on their own life experiences. In this sense, developing skills and understanding for personal awareness (in the private arena) precedes the awareness of the more general issues concerning citizenship (in the public arena). It is important to remember that the KS3 division between PSHE and Citizenship is premised on assumptions about what has been achieved in KS1&2. In planning for 11-16 year olds with special needs it may be appropriate to retain explicit links with PSHE goals and to draw on the KS1 and 2 PSHE and Citizenship guidance. Key Issue 3: Differentiation Differentiation is a term often used to describe the process teachers go through to make lessons accessible for pupils with learning difficulties. In fact differentiation lies at the heart of effective teaching and learning. Whether classes are organised by ability or not, all teachers must understand how to match work to the capabilities of individuals or groups in order to extend their learning. Differentiation is not simply planning more class work or different homework, it starts with a thorough understanding of the concepts to be taught and informs planning from the outset. Understanding how to do this should be at the core of evaluating and developing your own practice. (see page 2) Key Issue 4: Information You will not be expected to become an expert in all learning difficulties, but all staff are expected to know how to access the information required to do their job effectively. Key sources of information in mainstream schools include: Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils The Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO) who will be able to give you advice about specific types of learning difficulty and specific pupils. Individual Education Plans (IEP) which contain specific information on a pupil’s learning difficulties and targets. Assessment records that will indicate prior attainment for pupils in your classes. Useful links www.qca.org.uk Planning, Teaching and Assessing the Curriculum for Pupils with Learning Difficulties: General Guidelines Developing Skills Personal, Social and Health Education and Citizenship www.nc.uk.net Inclusion Statement explaining 3 principles: Setting suitable learning challenges Responding to diverse learning needs Overcoming potential barriers www.citizen.org.uk The education pages include a SEN section with links and free teaching resources. Fergusson, A and Lawson, H (2003) Access to Citizenship: Curriculum planning and practical activities for pupils with learning difficulties London: David Fulton Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils Differentiation in the classroom This section provides suggestions for practical approaches to try out. You may identify others from your own observations of classroom practice – this is one area where observing teachers from a variety of subject areas is likely to reveal a wide variety of strategies. (1) Differentiation by content / resources All pupils may work towards answering the same question, or work within the same project theme, but with a variety of resources. The teacher may decide to provide everyone in the class with all resources, or direct specific resources to specific pupils. For example, a project on a local planning issue may include some groups working with photographic evidence, some using maps, some interpreting statistics and others using newspapers and other written reports. (2) Differentiation by activities / task Here all pupils might have the same resources to use, but will be working on different questions or tasks. For example, the same local planning project might be differentiated by asking one group of pupils to describe key features, another to outline different perspectives of different groups, and another to evaluate proposals against established criteria. (3) Differentiation by organisation (a) Work groups On some occasions the teacher will want pupils to work in mixed ability groups so the most able can help the least able to access a group task. On other occasions, the teacher may decide that ability groups are more appropriate so that pupils are all likely to be working at a similar level to their peers. This helps to target resources, activities and support. (b) Paired work McNamara and Moreton (1997) identify paired work as distinctive from other grouping strategies because the relationship can be set up to explicitly focus on peer tutoring in which pupils review and assess together, and help each other to target set. (c) Whole class organisation Using the furniture to establish different patterns and groupings can facilitate different types of discussion – leading to differentiation in learning. This can include groups reporting back to others through ‘market-place’ activities, or expert groups regrouping to form new groups in ‘jig-saw’ activities, or working in three’s with paired conversation and an appointed observer. Used deliberately, with a clear rationale, these can be powerful strategies for meeting the needs of all pupils in class. (4) Differentiation by support In some lessons you may plan to spend additional time with pupils who may experience difficulties, or to extend those who may need pushing to reach higher levels. You may also have the help of a teaching and learning assistant. (5) Differentiation by gradation / extension Gradation implies that all pupils will work with the same resources, but questioning will become more difficult as the lesson continues. A more sophisticated version may require all pupils to start the lesson with a common activity, to be followed by a range of ‘extension’ work to move pupils on at a different pace or level. (6) Differentiation by response / outcome In Citizenship where there is no tiered GCSE, pupils get used to working on open ended questions and producing an individual response that can be levelled. Careful planning may help you set common tasks with common resources, but it is likely that teaching (as opposed to assessment) will also draw on one of the previous strategies. Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils It is important to remember that a single lesson may include any number of these activities and strategies. Also the balance between different strategies should be influenced by the precise nature of the learning difficulties pupils have in your class. Select any of the activities in the other briefing sheets in this series and think about how you could develop the classroom activities in classes with pupils of mixed ability. You could work on classes you are teaching or imagine the following pupils with specific learning difficulties: (a) Adrian has Attention Deficit Disorder and can be disruptive during class. (b) Claire has literacy problems, is a poor reader, and struggles to write legibly. (c) Narinda has Asperger’s and finds it difficult to work in groups. (d) Hassan has Down Syndrome and has difficulty formulating complete sentences and problems with his short term memory. Each of these specific learning difficulties might require some research. You should aim to create an inclusive teaching plan and justify your differentiation strategy. Useful resources: McNamara and Moreton (1997) David Fulton Understanding Differentiation: A Teachers’ Guide London: Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils Citizenship in the school community Thinking about differentiation requires teachers to consider the balance between individual pupils’ needs and whole class planning. It requires us to think about the nature and purposes of the relationships within a classroom and to maximise them for learning. Similarly Citizenship requires us to think about the ways in which we use the whole school community as a resource for inclusive teaching. For many pupils with learning difficulties the school community will provide a relatively safe community in which to learn about citizenship concepts and to develop their skills. Thinking about power One special school used the school itself as the starting point for a unit of work on power. Pupils started by undertaking a project on themselves, their friends and families and who had the power to make decisions within these groups. Then they were sent round the school to photograph adults who worked in the school and returned to sort the images into order, in relation to individual’s power in the school. They then discussed the nature of the power each person had and the relations between them, before inviting some staff members to be interviewed. A series of visits to the local community followed, to discover some of the services provided by the local council and the people responsible for running them, from sport centre managers to councillors. Taking a longer time to approach a single concept, revisiting it in different contexts and building on personal knowledge were all deliberately planned features of this project, to ensure it was accessible for a range of pupils with moderate learning difficulties. How else could this approach be developed in your school? What other Citizenship concepts or elements of knowledge could be planned with this model? Thinking about change Another project to get pupils involved in thinking about the school as a community centres around establishing how things get changed within the school. This project might follow on from the previous one, in which powerful people in the school are identified. Pupils are asked to photograph aspects of the school they think are good and aspects they think are problematic, dangerous or just not very nice. Pupils pool their images and discuss what they like about some areas and what concerns them about others. Having decided which areas are of most concern to them, pupils need to imagine what they could be like in the future. How could they be improved? What are the implications of the changes they would like to see – costs, resources, time etc? This kind of project can be developed through creating questionnaires to find out what other people think of the proposals before finalising a plan and then devising a plan of action to try to achieve it. What are the practical obstacles that might hinder such a project? What measures could you take to minimise any risks? What would the learning outcomes be of such a project? How would you review this project for pupils with learning difficulties? Pupils who were Gifted and Talented? Consulting young people Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils Many schools make decisions without consulting pupils and this means opportunities are lost for these kinds of enquiry based projects. It is important to see them as part of the strategy schools should be implementing on consulting young people, and for many pupils with learning difficulties, such activities are important to enable them to participate in consultation seriously. Structured activities and time to think and formulate ideas about issues are important to enable everyone to voice a valid opinion. School and class councils These can also be important vehicles for inclusion and many special schools have student councils that take an active part in the life of the school and meet regularly with other members of the local community – other school council members, local government and service providers. One school has developed a system of school council working groups which provide a broad range of pupils with opportunities to get involved in areas of interest to them from toilet re-design, fund-raising, curriculum consultation, sports events etc. Even if not all pupils are involved, school councils provide an immediate experience of democracy at election times. Similarly developing class councils is also important to provide everyone with experience of ‘representative’ democracy. Useful resources: Working Together: Giving children and young people a say (DfES 0134/2004). Available in the teachers’ section at : www.wiredforhealth.gov.uk Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils Citizenship in the community One of the themes that emerge from the earlier list of strategies for differentiation is that many of them require the teacher to plan for active, group-based learning. Adopting group work strategies not only helps with differentiation, but also helps to develop skills of participation and communication within Citizenship classes. Building a skills-based approach in which participation drives the project may well help some pupils achieve more than basing work mainly in covering knowledge and understanding. Many special schools have demonstrated that the active dimension to Citizenship is in many ways the most accessible aspect of the subject. Example 1 School linking This can be a powerful way to help pupils with SEN build relationships and Citizenship experiences. For example, one school has matched pupils with moderate learning difficulties to KS1 readers in a local primary school to act as reading buddies. This provides help to the KS1 teacher and enables the secondary school pupils to experience responsibility within a real project. Example 2 Eco-schools Many special schools work with environmental schemes which enable pupils to engage with a wide variety of activities. School based programmes can provide a forum for pupils to identify problems, plan a programme of activities and carry it out and review it. The Eco-schools approach enables pupils to get recognition for their work. Such projects also provide opportunities to work with groups outside the school such as Groundwork or other local organisations. For more information on the scheme and links to environmental groups visit: www.eco-schools.org.uk Assisted participation Although many pupils with learning difficulties will find active and participative work accessible, this is obviously not an unproblematic area. First, some pupils with severe learning difficulties will be unable to work independently and so some of the forms of participation envisaged by Hart, in his ladder of participation, may not be accessible. Second, some of the examples above may seem to be only vaguely related to the Citizenship curriculum. The link between participation and developing knowledge and understanding about Citizenship is difficult to discern. Youth initiated shared decision making Youth initiated and directed Adult initiated shared decision making Youth consulted and informed Youth assigned but informed Non participation: SEN participation: Tokenism Join in with peers Decoration Show a positive interest in activity Manipulation Develop sense of belonging to group Adapted from Roger Hart (1997) Children’s Participation: From tokenism to citizenship UNICEF Student Briefing Paper – CE with SEN Pupils Fergusson and Lawson (see page 1) observe that some pupils will require such high levels of direction and support that their participation may seem superficial. However, they argue that such pupils can nevertheless be helped to build up their ‘action competence’, that is an increasing awareness of their role and the skills required to be an active citizen. For some pupils, the ladder diagram above may need to be extended (e.g. with the right hand steps) to illustrate that participation can be demonstrated by taking an active interest in events, rather than being passive, and developing a positive sense of belonging, rather than a negative one. Ultimately they argue, as with all the aspects discussed so far, that teachers must keep a broad view of the nature of ‘participation’ and develop activities that are relevant to the pupils they are teaching – a pupil’s progress is relative to prior achievement and our teaching must recognise this. The role of reflection There is a danger in all active citizenship projects that pupils remain focused on the activity, at the expense of thinking about their learning. Not only is reflection on participation a curriculum requirement, it is the vital step to enable pupils to understand their learning and the connections between the current activity and their previous learning. It is important to think about ways in which this reflection can be built in to the activity in an accessible way. For each of the examples above, describe a reflection and evaluation strategy the teacher could implement that would be accessible to all pupils.

![afl_mat[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005387843_1-8371eaaba182de7da429cb4369cd28fc-300x300.png)