(1632-1704) John Locke

advertisement

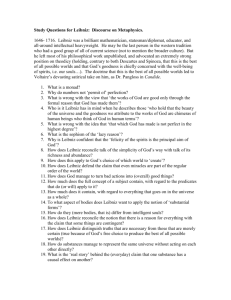

John Locke (1632-1704) he British philosopher John Locke was especially known for his liberal, anti-authoritarian theory of the state, his empirical theory of knowledge, his advocacy of religious toleration, and his theory of personal identity. In his own time, he was famous for arguing that the divine right of kings is supported neither by scripture nor by the use of reason. In developing his theory of our duty to obey the state, he attacked the idea that might makes right: Starting from an initial state of nature with no government, police or private property, we humans could discover by careful reasoning that there are natural laws which suggest that we have natural rights to our own persons and to our own labor. Eventually we could discover that we should create a social contract with others, and out of this contract emerges our political obligations and the institution of private property. This is how reasoning places limits on the proper use of power by government authorities. Regarding epistemology, Locke disagreed with Descartes' rationalist theory that knowledge is any idea that seems clear and distinct to us. Instead, Locke claimed that knowledge is direct awareness of facts concerning the agreement or disagreement among our ideas. By "ideas," he meant mental objects, and by assuming that some of these mental objects represent non-mental objects he inferred that this is why we can have knowledge of a world external to our minds. Although we can know little for certain and must rely on probabilities, he believed it is our Godgiven obligation to obtain knowledge and not always to acquire our beliefs by accepting the word of authorities or common superstition. Ideally our beliefs should be held firmly or tentatively depending on whether the evidence is strong or weak. He praised the scientific reasoning of Boyle and Newton as exemplifying this careful formation of beliefs. He said that at birth our mind has no innate ideas; it is blank, a tabula rasa. As our mind gains simple ideas from sensation, it forms complex ideas from these simple ideas by processes of combination, division, generalization and abstraction. Radical for his time, Locke asserted that in order to help children not develop bad habits of thinking, they should be trained to base their beliefs on sound evidence, to learn how to collect this evidence, and to believe less strongly when the evidence is weaker. We all can have knowledge of God's existence by attending to the quality of the evidence available to us, primarily the evidence from miracles. Our moral obligations, says Locke, are divine commands. We can learn about those obligations both by God's revealing them to us and by our natural capacities to discover natural laws. He hoped to find a deductive system of ethics in analogy to our deductive system of truths of geometry. Regarding personal identity, Locke provided an original argument that our being the same person from one time to another consists neither in our having the same soul nor the same body, but rather the same consciousness. http://www.iep.utm.edu/locke/ Leibniz: Metaphysics e German rationalist philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), is one of the great renaissance men of Western thought. He has made significant contributions in several fields spanning the intellectual landscape, including mathematics, physics, logic, ethics, theology, and philosophy. Unlike many of his contemporaries of the modem period, Leibniz does not have a canonical work that stands as his single, comprehensive piece of philosophy. Instead, in order to understand Leibniz's entire philosophical system, one must piece it together from his various essays, books, and correspondences. As a result, there are several ways to explicate Leibniz's philosophy. This article begins with his theory of truth, according to which the nature of truth consists in the connection or inclusion of a predicate in a subject. Together with several apparently self-evident principles (such as the principle of sufficient reason, the law of contradiction, and the identity of indiscemibles), Leibniz uses his predicate-insubject theory of truth to develop a remarkable philosophical system that provides an intricate and thorough account of reality. Ultimately, Leibniz's universe contains only God and noncomposite, immaterial, soul-like entities called "monads." Strictly speaking, space, time, causation, material objects, among other things, are all illusions (at least as normally conceived). However, these illusions are well-founded on and explained by the true nature ofthe universe at its fundamental level. For example, Leibniz argues that things seem to cause one another because God ordained a pre-established harmony among everything in the universe. Furthermore, as consequences of his metaphysic, Leibniz proposes solutions to several deep philosophical problems, such as the problem of free will, the problem of evil, and the nature of space and time. One thus finds Leibniz developing intriguing arguments for several philosophical positionsincluding theism, compatibilism, and idealism. This article is predominately concerned with this broad view of Leibniz' s philosophical system and does not deal with Leibniz's work on, for example, aesthetics, political philosophy, or (except incidentally) physics. Leibniz's "mature metaphysical career" spanned over thirty years. During this period, it would be surprising if some of his basic ideas did not change, but, remarkably, the broad outline of his philosophy does remain constant. http://www.iep.utm.edu/leib-met/