The continued existence of the jury reinforces the principle that no

advertisement

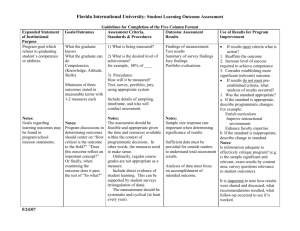

JURY EVALUATION The continued existence of the jury reinforces the principle that no man is to be fined or imprisoned merely by the will of the state, but only by the judgment of his equals. It is thus part of a bargain, as E P Thompson writes, between the law and the people: the jury attends in judgment not only upon the accused but also upon the justice and humanity of the law. Lord Devlin described the jury in 1956 as "the lamp that shows that freedom lives", and suggested that no tyrant could afford to leave a subject's freedom in the hands of twelve of his countrymen. Two years later Lord Birkett said the jury introduces into the law an element of community sentiment and fairness: a jury can do justice where a judge has to follow the law. R v Blythe (1998) A man D was charged with cultivating cannabis with intent to supply it to his terminally ill wife W, who suffered severe pain from multiple sclerosis. Judge Hale told the jury at Warrington that the defence of duress of circumstances was not available in such a case, even though D feared W might commit suicide, but the jury disregarded this instruction and found D not guilty. D was convicted of simple possession and fined £100. R v Melchett (2000) A large number of Greenpeace supporters entered a field and destroyed part of a crop of genetically modified maize. They were charged with causing criminal damage, but pled the statutory defence (under s.5 of the Criminal Damage Act 1977) that they honestly believed the destruction was reasonable and necessary to prevent damage to other crops. The first jury were unable to reach a verdict, but the defendants were acquitted by the jury at the retrial. Quayle & others v R (2005) In several conjoined appeals involving the possession and use of cannabis for medical purposes, the appellants argued inter alia that the judge should have reminded the jury of their right to acquit regardless of the law. The Court of Appeal disagreed: the jury has a well-established power to return a verdict of not guilty, said Mance LJ, whatever the law and however clear it may be, but to require the judge to direct the jury that they should weigh in the balance the pros and cons of enforcing the clear policy of a statutory scheme in any particular case is a different matter. It would involve a positive invitation to the jury to act contrary to the law and to take over the role of the legislative authorities. The fact that the jury are lay people without legal training really should not matter. They do not decide questions of law but questions of fact, including questions of reasonableness and so on that are eminently suitable for decision by ordinary people. In their book Jury Trials (1979), on the other hand, Baldwin and McConville set out plainly the logical argument against the jury as it is currently constituted. Twelve individuals, they wrote, often with no prior contact with the courts, are chosen at random to listen to evidence (sometimes of a highly technical nature) and to decide upon matters affecting the reputation and liberty of those charged with criminal 1 JURY EVALUATION offences. They are given no training for this task, they deliberate in secret, they return a verdict without giving reasons, and they are responsible to their own conscience but to no one else. After the trial they melt away into the community from which they are drawn. Although jurors do not need any prior knowledge of the law, their inexperience and lack of legal knowledge means that important points of evidence may have to be given several times and then explained at length, thereby adding to the length and expense of the trial. The rules of evidence also reflect the need to keep from the inexperienced jury a lot of prejudicial but potentially relevant evidence about other offences with which the defendant (or witnesses) may have been charged, and limiting the admissibility of hearsay evidence whose reliability they might have difficulty in assessing. Jurors are not subject to any kind of intelligence test, and may be unable to cope with difficult medical, financial or technical evidence. Complex fraud trials have given rise to particular concern, because most ordinary jurors do not have the training or expertise for the detailed study of pages of accounts, and the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (not yet fully in force) makes provision for judge-only trials in some such cases. But there is a risk in other cases that jurors may put too much faith in the evidence of "expert" witnesses: it was largely Dr Meadows' testimony about the likelihood of two innocent "cot deaths" in the same family that led to the wrongful conviction of Sally Clark. Jurors may also be influenced by the media, or bribed or threatened by the defendant's friends, or may give decisions based on prejudice. Research by the psychologist Richard Wiseman (reported in October 1999) showed that many people (and by extension, many jurors) still have preconceived ideas of what a criminal looks like. Two large groups of TV viewers were shown a summary of a court case: the evidence was exactly the same in each case, but one defendant had a broken nose, deep set small eyes and an unsymmetrical face, while the other was attractive with blue eyes and an angelic symmetrical face. Eleven per cent more viewers convicted the defendant fitting the criminal stereotype. The jury represents the public at large, but in some ways it does so too well - the "ordinary standards of common decency" can all too easily become the standards of common prejudice. Juries in the past were reluctant to convict a driver charged with manslaughter, identifying too easily with the man in the dock, and it was necessary to create the special offence of "causing death by dangerous driving". But in other cases, perhaps involving serious child abuse, the jury may reflect the popular prejudice against a possibly innocent defendant and forget that its job is not to reflect public revulsion at a particularly horrible crime, but rather to decide dispassionately whether the person in the dock is the person who committed it.) Jurors sometimes misbehave: in December 2000, a ten-week trial at the Old Bailey had to be stopped because an "improper relationship" had developed between a 2 JURY EVALUATION female juror and a male police officer acting as jury bailiff. The defendants' previous trial (on the same charges) had been stopped when the jury were found to be playing cards when they should have been considering their verdict. The jury is not required to give reasons for its decisions, and (although this can never be checked) there are strong suspicions that some decisions are based on wholly irrelevant factors such as the personality of one of the barristers, a prejudice in favour of (or against) the police, or perhaps something even more extraordinary. R v Young [1995] D was charged with two murders and was convicted. It subsequently came to light that during an overnight stay at a hotel, four of the jurors (possibly under the influence of drink) had supposedly contacted one of D's alleged victims using a ouija board, and had obtained confirmation that D was the killer. The Court of Appeal allowed D's appeal against conviction and ordered a new trial (at which D was again convicted). The statutory prohibition on inquiries into the jury's deliberations applied even to the Court of Appeal, said Lord Taylor CJ, but did not apply to events that occurred during the overnight break in their deliberations. [Quaere: Would it have been any different if the jurors had prayed to God for guidance?] We have noted already that juries can historically disregard the law in order to do justice, but perhaps they sometimes go too far. R v Owen (1992) D's son was killed by a careless driver T, who was sent to prison for twelve months. D felt this was not enough, and when T was released D went to T's home and fired at him with a sawn-off shotgun, causing injuries to T's back and arm. D was tried for attempted murder and malicious wounding with intent, but the jury at Maidstone Crown Court acquitted him and some members later congratulated him on what he had done. It is questionable whether jury service is an efficient use of professional people's time, particularly since the 2004 reforms making it almost impossible even for doctors, MPs and self-employed business people to secure an exemption. Shortly after the new rules were introduced, Lord Justice Dyson was randomly selected for jury service and had to take two weeks' leave from the Court of Appeal to sit as a juror in his local Crown Court. Cherie Booth (a practising barrister and Recorder) was similarly called shortly after her husband had ceased to be Prime Minister in 2007. However, research by the New Zealand Law Commission (published in 2001) "showed no evidence that the jury is not impartial and democratic, [but] highlighted the care and commitment that jurors bring to their task, the crucial aspect of community and civic participation, and the educative function of jury service." It dismissed the argument that juries cannot understand expert evidence: even where there is difficult scientific or financial evidence to consider, the better answer is usually to explain it more clearly and carefully rather than to remove the jury. Only a 3 JURY EVALUATION very small proportion of trials, suggests the report, are too long and perhaps too complex for a jury. 4