Early Japan

advertisement

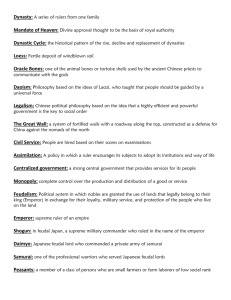

Japan’s Early Historic Period: The Imperial Court (A.D. 400-783) Prior to A.D. 400 regional clans called uji ruled separate areas of Japan. Though no political unity existed the various clans were united by a common religion called Shinto. Shinto, meaning “The Way of The Gods,” was based on worshipping nature by revering kami- usually defined as gods but more accurately meaning “Something that is superior.” For instance an ancestor or a beautiful mountain could become kami, though the most important kami were the divine spirits of nature. Each uji worshipped a protector kami. Amatersau, the Sun Goddess, was the most important kami because she “gave life to all things.” The leader of the uji that worshipped Amaterasu as its main kami gained great importance during this era, eventually becoming the emperor of Japan. Japanese traced their belief on the emperor’s divinity to Amaterasu, who according to legend sent her grandson Ninigi to rule Japan. Ningi’s grandson the great Jimmu Tenno (“divine warrior”) led his uji from Kyushu to the Yamato Plain, a fertile but small (10 by 20 miles) region of Honshu on Japan’s Inland Sea. There, through war and marriage, he established the powerful Yamato clan and became Japan’s first emperor. As the supposed great-great grandson of the goddess Amaterasu and a direct link to the kami, the emperor was the most important person in the Shinto religion. Every emperor of Japan, from Jimmu’s time forward has been directly related to Jimmu and therefore treated as a descendant of the gods. As symbols of their divine power, emperors kept three treasures: a magnificent curved jewel-said to have been taken from the steps of heaven; a bronze mirror that belonged to Amaterasu; and an iron sword, representing the emperor’s strength. Venerated as religiously supreme because of his divine ancestry, the emperor held little secular power outside the Yamato Plain. Leaders of other uji held political sway in their respective regions. Central government was by a council of state, made up of the heads of the most powerful uji, while the emperor was considered more of a first-among- equals. This situation created bloody rivalries between various uji as they fought to gain the most important position in the government, that of chancellor, or chief advisor to the emperor. The first clan to earn this position was the Soga, who manipulated the choice of emperor from A.D. 552 to A.D. 645. During the Soga reign, influences from China shaped a distinctive Japanese culture. In A.D. 405 a Korean scholar named Wani arrived at the Japanese royal court to teach the Yamato crown prince how to read and write Chinese. This signaled a period of cultural borrowing that would remain strong until the early ninth century. For example, despite the fact that spoken Japanese and Chinese have no phonetic similarities, the Japanese still adopted Chinese character script because it was the only one they knew of. So, when the Chinese Characters for sun and source. In Chinese those characters together pronounced “jihpen,” from which we get Japan. In time, the Japanese developed a script called Kana, which assigns phonetic sounds to simplified characters. After the sixth century, China’s culture continued to influence Japan. Memorization of Chinese poetry became a popular pastime. Japanese aristocrats collected Chinese art, which with it emphasis on Landscapes, influenced Japanese art. Chinese architectural styles such as gently curving tile roofs became popular in upper-class Japan. Chinese culture was particularly valued at the court of Prince Shotoku (reined A.D. 587-622). Scholars who traveled to China to study Chinese culture were given high-ranking positions upon their return. Shotoku adopted the Chinese system of ranking for his courts nobles and advisors. Each rank was identifiable by certain distinctions of apparel: the color of a cap, the length of a gown, or the size of a fan. Only the highest-ranking officials could enter the emperor’ chambers. Shotoku also adopted the Confucian calendar and Confucian legal ideals. Perhaps the greatest purveyor of Chinese culture in Japan was Buddhism. Legend traces the first serious arrival of Buddhism in Japan to A.D. 522 when along with a request for military help, the Paekche kingdom in Korea sent several volumes of Buddhist scripture (written in Chinese), a bronze image of Buddha, and a letter recommending careful consideration of a “most difficult, but certainly the world’s most excellent doctrine.” After initial difficulty being integrated with Shino, Buddhism became extremely popular in Japan, especially among the upper classes. By the end of the seventh century, there were 545 Buddhist monasteries, with a priesthood numbering in the thousands. Another aspect of Chinese culture was incorporated into Japanese life when in A.D. 646 Emperor Tenchi proclaimed the Taika Reforms, sweeping changes based on Chinese Confucian philosophy. The Reforms were intended to model Japan’s government after the Tang dynasty in China. Emperor Tenchi summoned the leaders of Japan’s mightiest uji to the imperial court, where they were gathered under a giant tree. Emperor Tenchi then proclaimed a vast land reform program, which stated that all rice-producing land was now the property of the throne. The land would be distributed to peasants, who would in turn pay taxes to the emperor. This system would be administered by officials appointed by the emperor. Officials would be chosen from uji leaders. The assembled nobles swore their allegiance-in line with the Confucian ideal that citizens had a responsibility to obey their leaders-and vowed, “Heaven will send a curse and earth a plague (on those that disobey), demons will slay them, and men will smite them.” Behind the Taika reforms was the notion that the emperor was supposed to be supreme, not just religiously but also politically, like the emperor in China. The importance of the Reforms was that power over land became, theoretically, concentrated in the hands of the emperor. In practice, regionally leaders retained their land, but not until the emperor and his ministers officially appointed them as tax collector. This practice set the stage for later consolidation of real power in the hands of the emperor’s chancellor. In A.D. 710, the Japanese adopted the Chinese idea of a fixed capital and chose Nara, situated in the center of the Yamato plain, as the site for the imperial capital. The population of Nara, which was modeled after the Tang capital at Xi’an (Changan), reached 200,000 made up of former uji leaders who staffed the emperor’s government, Buddhist and Shinto priests, craftspeople who built and refurbished the city’s buildings, capital’s upper class. Though all aspects of Chinese culture flourished at Nara, Buddhism’s influence became prominent. Nara’s streets were crowded with temples and Buddhist monasteries, whose influence quickly grew at the court. Leading monks plotted to put their favorite prince on the throne, interfering with day-to-day government. Eventually in A.D. 784 the emperor Kammu decided to move the capital to someplace “priest proof.” At first he relocated to Nagoka, but after 10 years it proved to be an illomened site. So in A.D. 794, Kammu chose Heian-kyo, which means “Peace and Tranquility,” 30 miles from the powerful Nara Buddhist monasteries. Refined Court Life during the Heian Period (A.D. 794-1185) The Fujiwara used their control over the emperor to become dominant in Japanese economics and politics. Members of the Fujiwara clan were given most of the highranking posts in the central government’s most important ministries. In A.D. 1027, 22 of the 24 highest ranking posts at court were occupied by Fujiwaras. The most powerful Fujiwara regent was Michinaga (ruled A.D. 997-1027), who oversaw the accumulation of tremendous wealth in the hands of the Fujiwara in the form of rice-producing land. During the Heian period, the Fujiwara leaders advised the emperor to give tax-free estates, called Shoen (sho=village, en=farmland), as gifts or rewards to various nobles and clans. The most profitable shoen were granted to members of the Fujiwara, so that in A.D. 1025 a dissident member of the Fujiwara clan wrote, “the first family has not left even a speck of earth for the public domain.” By the end of the Heian period, Japan was divided into 5000 shoen and the government had almost no land. During the Heian period, the emperor’s role became almost completely ceremonial. His primary function was to perform the many ceremonies that made up religious festivals and celebrations. These services became more and more ornate as Heian culture developed a distinctive style marked by rigorously followed complex customs. An account of a monastery dedication attended by the emperor Ichijo in A.D. 1022 describes the ostentatious nature of this court life: “The monarch’s arrival was heralded by a crescendo of drums, strings and reeds. Jeweled nets were suspended from the branches of the plants fringing the pond. Boats adorned with gems idled in the shade of trees, and peacocks strutted on an island in the middle. Gold, silver, and lapis, lazuli (an opaque blue gem) were strewn on the monastery floor, and dancers performed in a room suffused with incense.” Attending the emperor at his life of pomp and ritual were the nobles, descendants of the leaders of the first important uji. Heian nobles at the Kyoto court led a life focused on beauty and manners, guided by an intense courtly code called miyabi. Miyabi stressed appearance, restraint, and decorum. It was thought horribly rude to laugh with one’s mouth open. While eating, court nobles never touched food with their hands and avoided ever letting another diner see their mouths. Sometimes letters would be returned unread if the paper had been folded improperly, or if the handwriting was considered unrefined. Men made their own perfume, and the famous nobles were known by their individual scents. Rules of clothing were so closely followed that a women would be shamed and ostracized if one of the 12 layers of thin silk gowns she wore had a sleeve 1 inch longer than the customary length. Combining colors was essential to apparel so much so that one noble remarked of a fellow courtesan that her outfit of 12 multicolored robes “really not very bad-only one color was a bit pale.” Attention to appearance in the miyabi was most noticeable in the ideal of beauty and personal appearance of the court nobles. The perfect face was round and white with a tiny mouth. Both sexes applied liberal amounts of white powder to their faces. Women used lipstick in an attempt to make their mouths look smaller, and applied red rouge to their cheeks. Men wore pointy beards on the tips of their chin, and sometimes mustaches. Women grew their hair as long as possible, with the ideal being to have locks that were longer than the person was tall. People were advised to sleep only at night so no one would see them asleep because they were believed to be uglier when lying down. Nobles spent their days at the court leisurely pursuing pastimes influenced by Chinese culture. Memorization of Chinese poetry and the ability to compose rhymed couplets was essential in court life. Go, a Chinese board game played with white and black tiles, was popular. Men played a gamed called football (or kickball), a game much like modern foot bag in which players used their feet in an attempt to keep a small ball from touching the ground on a special court. Landscape painting was popular. Nobles attended the many Shinto ceremonies, festivals, and parties presided over by the emperor. During the Heian period a few noble women wrote diaries and fiction describing the lives of court nobles. Sei Shonagon offered a glimpse into the courtier’s life with her Pillow Book, a diary in which she noted all of the things that interested, attracted, and displeased her at the emperor’s court at the end of the tenth century. Murasaki Shikibu’s novel Genji monogatari (Tale of Genji) written around A.D. 1014, is considered a masterpiece of Japanese literature. Working at the palace, Shikibu’s became the center of a brilliant group narrates the story of the fictional Genji, the “shining prince” of the Heian court, who is an ideal courtier: the son of an emperor, a musician, poet, painter, dancer, kickball player, and talented lover. Murasaki’ tale recounts the love and anguish of the noble courtiers involved in the prince’s many romantic encounters. The isolated court life in Kyoto led to the political and military ascendancy of provincial nobles at the end of the Heian period. The tax revenue system established by the Taika reforms had completely deteriorated by this time, due mostly to the practice of granting shoen. Isolated from the shoen they owned in name only, court nobles could no longer control the provincial chieftains who were collecting the taxes that used to go to the emperor. The provincial nobles were totally different from Kyoto nobles; rugged and self-sufficient, they used private armies to battle rivals and increase their land holdings. By the end of the Heian period, the provincial nobles, the first samurai, ignored any imperial edicts they did not accept. Their wars and rivalries merged into a long battle between the Taira and Minamoto clans, who fought to replace the Fujiwara as controllers of the royal family. The Rise of Feudalism and the Mongol Invasion During the last years of the Heian period, two mighty clans, the Taira and the Minamoto, battled for power over the Kyoto government. In A.D. 1159, the Taira leader Kiyomori executed the Minamoto leader Yoshitomo, signaling victory for the Taira clan. Kiyomori became a virtual dictator dominating the emperor, the court nobles, and the leading Buddhist monasteries. The Taira had become the next Fujiwara clan, stacking the government with their own people and accumulating shoen for themselves. By the end of Kiyomori’s rule, people in Kyoto would say “If one is not a Taira one is not a human being.” Due to Yoshitomo Minamoto’s career, the Taira ascendancy was short-lived. Yoshitomo’s son Yoritomo was 12 when his father was beheaded. The young Minatomo prince fled to the remote Izu province in eastern Japan, where he was trained to be both a warrior and a scholar. In A.D. 1180 with any army of 27,000 loyal Minatomo followers and anti-Taira warriors, Yoritomo began a war to unseat the Taira from their roost in Kyoto. In A.D. 1183, the Taira fled Kyoto with the five-year-old emperor, Antoku, who was Kiyomori’s grandson. Finally, two years later, the Minamoto crushed the last Taira forces in a sea battle at Dannoura, in western Japan. The boy emperor drowned, severing the connection of the Taira clan to the royal family. Because he had freed the court from the clutches of the Taira, Yoritomo was embraced as leader by the royal family, and given the right to establish a new secular government at his headquarters in Kamakura, a small seaside village in eastern Japan. Yoritomo’s rule marked the beginning of a new era in which the warrior class and not the court nobles dominated Japanese society. This warrior class was called the samurai, literally “one who serves.” Unlike the court nobles in Kyoto, who lived a life of luxury and artistic pursuit, the samurai lived according to a code that was based on honor, respect, obedience, and total loyalty to those superior. Samurai revered fighting, embodying a fierce readiness to do battle. The symbol of the samurai was his long double-edged sword, which was a sacred object. Samurai gave their swords names, slept with them under their pillows and were often buried with them when they died. The government established in Kamakura during this period (A.D. 1185-1333) was called the Bakufu, which literally means “tent government.” In A.D. 1192, the emperor granted Yoritomo the title Seitaishogun, meaning Barbarian-Subduing Generalissimo, which signified his position as the chief military ruler of all Japan. The term was eventually shortened to Shogun. Under Yoritomo, Japan was organized along feudal lines. From his government seat in Kamakura, he parceled out land to his most trusted officials in exchange for which each titled lord (high-ranking samurai) owed a certain number of received. The lower samurai, loyal to their provincial lord, were in turn given smaller manors to maintain. Of every 12 acres, under a lower samurai’s rule, 2 acres had tax-free status. The other 10 acres were subject to taxes, due to both the local lord and the Kamakura government. The peasants lived off whatever might be left. Yoritomo and his successors always sought the permission of the emperor, still living in opulence in Kyoto. Except for a few brief instances, the emperor’s role was relegated to that of chief Shinto priest, whose divinity was never questioned, but whose authority did not extend beyond the royal palace in Kyoto. In all secular matters, the Shogun ruled. During the Kamakura period, three forms of Buddhism became popular. They were the Pure Land sect, popular among many commoners attracted to its assurances for the afterlife; the Lotus sect, founded by the Buddhist monk Nichiren (A.D. 1222-1282); and Zen Buddhism. Like Pure Land Buddhism, Zen Buddhism preached that literacy and scholarly debate were not the paths to enlightment. Instead people who dedicated themselves to a strict life of meditation and work in a monastery could achieve personal salvation during their lifetime. Having come to Japan from China, Zen Buddhism became very popular because samurai warriors were attracted by its emphasis on austerity, dedication and discipline. About 70 years after the death of Yoritomo, the samurai were tested when the Mongolos invaded Japan. In A.D. 1264, Kublai Khan became Great Khan of the Mongol empire. Establishing his capital at Beijing, he turned his attention to the East and sought the subjugation of southern China, Korea, and Japan. A decade later, 450 Mongol ships, carrying 15,000 troops, landed in Hakata Bay Kyushu island. For two days the local samurai chieftains fought against overwhelming odds to hold off the Mongols. During the second night of battle, with the Mongols retired to their ships to wait for daylight, a tremendous typhoon blew up and devastated the Mongol invasion forces. An estimated 13,000 men were lost, and the survivors retreated to Korea. Kamakura Bakufu ordered a massive mobilization to prepare for another invasion. Samurai on the western shores built new defenses, and an expanded army was put on 24hour alert. Every manor had to submit a list of eligible men and resources, all of which were subject to use by the Bakufu in case of attack. Religious services were carried out day and night, seeking protection of the gods. The emperor placed letters in the tombs of his ancestors, beseeching their intercession. The Kamakura regents copied out sacred Buddhist texts in his own blood. Meanwhile, Kublai Khan sent two missions with letters calling for Japanese capitulation. In both cases, the Bakufu destroyed the letters and beheaded the emissaries. Finally, after seven years of waiting, the Mongols again attached in A.D. 1281. A force of 150,000 Mongol soldiers and their Korean and Chinese allies sailed to Hakata Bay, where they were met by Japanese’s newly formed navy of light, swift ships prepared to out maneuver the large Chinese troop transports. After 50 days of bloody fighting, another typhoon whipped up on the Sea of Japan, again destroying the Mongol fleet. Eighty percent of the Mongol force was lost, and the survivors fled back to Korea. Japan rejoiced, believing their prayers had been answered. They called the typhoons kamikaze, or “divine winds,” because they felt that the gods and their ancestors had sent the typhoons to defend them. A great sense of national unity developed, and Japan felt its victory was a signal of the superiority of its way of life. Despite defeating the Mongols, the Kamakura Bakufu was unable to maintain control of Japan. The Japanese had reaped no spoils from the war, only debt. Many samurai became dissatisfied with Kamakura Bakufu, which was unable to repay them for their valiant defense of Japan because the royal treasury had been drained by the costs of the war. At their own expense, many samurai built defenses, outfitted fighting units with armor and weapons, and transported soldiers throughout the war period. Indebted to merchants, who had funded these military endeavors, these high-ranking samurai could not pay their vassal samurai the fees they traditionally gave them. Some were forced to sell their land in order to meet their debts. Peasants were forced by the lower samurai to relinquish more of their crops, in order to raise more money for making payments. Distressed peasants, strapped to the point of starvation in some cases, banded together and staged uprisings, called ikki. Some samurai, impoverished themselves and serving a lord who may have lost everything, led these rebellious peasants against their masters, carving control and discipline, became powerful enough to challenge the Bakufu. The sided with the royal family in Kyoto, and a period of civil war began. Eventually, in A.D. 1333, a force of disaffected samurai and imperial soldiers defeated the Kamakura forces bringing an end to the Kamakura Bakufu. 3.2D. Civil War and Reunification (A.D. 1333-1603) The period that followed the defeat of the Kamakura Bakufu was a time of political disunity in Japan. The emperor Godaigo proclaimed himself supreme ruler, hoping to return total power to the royal family. But because of the lack of control that had become prevalent during the end of the Kamakura period, Godaigo was unsuccessful. A regional military leader, Ashikaga Takuji, took advantage of the lack of stability and attacked the royal forces in Kyoto in A.D. 1335. A year later, Godaigo surrendered and abdicated the throne in favor of a young prince whom Takauji, as Shogun, planned to manipulate as his puppet emperor. Godaigo fled south, where he proclaimed himself rival emperor. His court was known as the southern court, and his supporters fought against the Ashikaga Shoguns until A.D. 1392. Takuji’s power was weakened when his son Tadayoshi rebelled against him in an attempt to become Shogun, increasing Japan’s disunity The Ashikaga Shogun was never able to be the supreme ruler that Kamakura Shoguns had been because various military generals had become powerful provincial warlords following the Mongol invasions, not unlike Takujii himself. They were not interested in turning over their regional power to another force in Kyoto. Yoshimitsu, the third Ashika Shogun(ruled A.D. 1367-1408), used his abilities as a negotiator and diplomat to bring the leaders of the three most powerful military clans, the Shiba, the Hosokawa, and the Hatakeyama, into an alliance with him. Leaders of the three families alternately served as the Shogun’s deputy. After Yoshimitsu’s death, the next Ashikaga Bakufu declined their services. This reignited rivalries between military families vying for powerful positions, and soon Japan was plunged into a hundred years of civil strife. The Onin War (A.D. 1467-1477) Ended the Ashikaga Bakufu and began one hundred years of civil strife called the Sengoku Jidai, or the “Age of the Warring States.” In 1441, the sixth Ashikaga Shogun was assassinated by a member of one of the leading military families. Thereafter, the Ashikaga Shoguns became the puppets of four military clans that battled to manipulate both the Shogun and the Emperor. The war itself began because Yoshimasa, the eighth Ashikaga Shogun, had named is brother Yoshimi as the heir. But in 1467, Yoshimasa’s wife gave birth to a son, Yoshihisa. Yoshisama backed by the Yamana family, wanted his new son to succeed him, but Yoshimi, with the support of the Hosokawa family, still laid claim to the position. The two rival factions declared war, and Kyoto erupted into fighting. In time, most of the leading families in Japan became involved in the Onin War, which was fought mainly in Kyoto and the surrounding countryside. Most of the capital city was destroyed as soldiers burned and looted temples and monasteries. Contemporary accounts claim that “after the major battles the streets were choked with corpses, and cartloads of severed heads were collected as trophies.” Political life in Japan completely changed during the years A.D. 1467-1573. The positions of Emperor and Shogun no longer held any political weight. Instead power belonged to whoever could win it in a fight. A new social order based on military power replaced the traditional order based on honor and ancestry. Lowranking samurai rose to defeat samurai of noble birth, bands of peasants fought local officials, and trusted vassals turned on their lords in bloody power grabs. This new social order was called the era of ge koku jo, or those below subjugating those above. By the end of Sengoku Jidai, when ge koku jo prevailed, Japan had been divided into roughly 140 independent states, each ruled by a daimyo. In this sense, daimyo referred to the person actually ruling the land, unlike previous eras when daimyo were official vassals of the Shogun. Three types of daimyo emerged from the chaos of the ge koku jo: traditional families that survived the political upheavals, local military leaders who captured a state of their own, and lowly samurai who rose into positions of great power. These positions changed often as fighting plagued Japan: of the 142 daimyo families ruling in A.D.1543, only 45 still held their positions 30 years later. The end of Sengoku Jidai began with the career of Oda Nobunaga (ruled A.D. 1534-1582). Nobunga, leader of the centrally located Owari province, used brilliant military maneuvers to consolidate control of central Japan. In 1560, he led a surprise attack against forces of the Imagawa clan that outnumbered his soldiers ten to one, capturing them unawares and destroying them. One of the first Japanese generals to employ firearms, he used them to defeat the Matsunaga clan and capture Kyoto in 1568. Nobunga subjected rival clans in western Japan, before turning his attention to the east, where Mori clan and the Pure Land sect Buddhist forces allied to fight the Oda army. Nobunga was considered ruthless, and he especially despised Buddhist monks, whom he saw as rivals to his power. He once had 150 monks burned alive for performing burial rites for the leader of a rival clan. Later, he ordered the destruction of the entire Mt. Hiei monastery, killing 1,600 people. In 1582, before he could achieve total victory-he had gained control of 32 of the 66 provinces-a traitorous and resentful general named Akechi Mitsuhide rebelled against Nobunaga, trapping him in a temple in Kyoto. Rather than be captured, Nobunaga committed seppuku, ritual suicide by cutting one’s own abdomen with a knife. Nobunga was followed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (A.D. 1536-1598), who came closer to uniting all of Japan under his rule. Hideyoshi, son of a peasant, became ruler of all Japan because of the unsettled nature of the Sengoku Jidai. He had risen through the ranks of the Oda family army, startubg as Nobunaga’s sandal carrier. At the time of his death, Nobunaga had named Hideyoshi chief general of his army fighting in the east. When Hideyoshi heard of Nobunaga’s death, he returned to Kyoto and defeated the traitorous Akechi. Hideyoshi then resumed Nobunaga’s quest to unify all the independent, warring daimyo under the rule of one person. He was much more diplomatic than Nobunaga had been and used negotiations whenever possible to pacify rebellious daimyo. By 1590, after eight years of fighting and negotiating, Hideyoshi brought all 66 daimyo into a feudal agreement whereby their land holdings became fiefdoms granted by Hideyoshi. Powerful rival daimyo that could not be militarily subjugated were brought into treaties with Hideyoshi’s allies, thereby forging a fragile unity. The most powerful daimyo, Tokugawa Ieyasu, agreed to this arrangement when Hideyoshi traded him the important Kanto province, an enormous fiefdom in eastern Japan, for control over Kyoto and the central provinces. 3.2E. Life in a Castle-town During the Tokugawa Period (A.D. 1603-1868) Japan entered period of unity and growth with the ascendancy of Tokugawa Ieyasu to the position of Shogun in A.D. 1603. Ieyasu, the leader of the powerful Tokugawa clan, had long been a rival of Oda Nobunaga and Hideyoshi Toyotomi. Realizing that he could not defeat him, Hideyoshi had made Ieyasu one of his trusted generals. Upon his death Hideyoshi had named a council of leading daimyo to succeed him until his son came of age. But Ieyasu had no intention of serving under another Toyotomi, or sharing power with other daimyo; he hoped to realize the dream of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi of uniting all Japan under his control. After five years of ruthless fighting and shrewd negotiations, Ieyasu brought all the daimyo under his effective control. He became Shogun in 1603 and established the Tokugawa Bakufu in Edo, the site of present-day Tokyo. To maintain complete control of Japan, and to insure that his heirs would be able to do the same, Ieyasu made two important policy decisions. First he sought to eliminate Christianity. As an extension of European power, Ieyasu felt Christianity posed a serious political threat to Japanese sovereignty. The first Christians had come to Japan in the 1540s, and for 70 years they had prospered. By 1610, Jesuit missionaries had converted upwards of 700,000 Japanese. Then Ieyasu became wary of the political goals of the Spanish and Portuguese. Ieyasu issued an edict banning Christianity four years later. All Japanese had to join a sect of Buddhism and register at a local temple. The third Tokugawa Shogun, Iemitsu, openly persecuted Christians, executing as many as 6,000 people by 1640. The Tokugawa Bakufu then decided to gone step furthering insuring the unity of the country: an edict was issued in 1639 that forbid any person from coming into Japan. The Bakufu forbade travel abroad, and anyone living overseas was not allowed to return to Japan. Ships big enough to sail overseas were destroyed. The only foreigners allowed on Japanese soil were the Dutch (2 ships a year) and the Chinese (30 ships a year), who were limited to the small island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor. Japan was effectively cut off from the rest of the world. Another way Ieyasu established control was to implement a strict social order based on Confucian social principles. The system divided the Japanese populace into four hereditary classes: the shi (samurai), no (peasants), ko (artisans), and sho (merchants). At the top of the shi class were the daimyo, direct vassals of the Tokugawa family who received fiefs sized in proportion to their relation to the Tokugawa family. There were about 270 daimyo. Lesser daimyo served as the retainers of their regional daimyo. To control the daimyo and limit the wars of the previous era, the Tokugawa Bakufu instituted the policy called sankinkotai, which required that daimyo spend every other year in Edo. The daimyo’s families were required that each daimyo spend every other year in Edo, so that if a daimyo led a rebellion in his province, the Shogun had his family as hostages. Checkpoints were set up around Edo to make sure no daimyo left Edo with their wives, and a limit was imposed on how many retainers a daimyo could take with him on his trips back and forth from the capital. In addition, daimyo marriages had to be approved by the Bakufu, and no daimyo could repair his castle without Bakufu permission. An elaborate system of spies was developed to monitor the actions of less-trusted daimyo. Daimyo castles became the center of peaceful Japanese society during the Tokugawa Bakufu. Prior to the stability of the Tokugawa era, samurai spent most of their time fighting. After peace was established, samurai became government officials working for the Bakufu. During this time of peace, the samurai developed an unwritten code of ideal behavior called Bushido, or “The Way of the Warrior.” Bushido was based on the concept of honor, which was more important than money or fame. It stressed simplicity and demanded total loyalty, so that every samurai be prepared to die for his master when the time came. Daimyo, the chief officials, ruled the provinces from their castles, collecting taxes for the central government and enforcing rules and laws on the emperor’s subjects. The castles, mostly built during the Sengoku Jidai, were beautiful fortresses of grace and strength. High, thick walls, labyrinthine passageways, and deep moats created a defense system intended to funnel attacking troops into bottleneck traps from which archers and stone throwers could slaughter the enemy. Behind the walls and moats sat the stately castle buildings, dominated by at least one towering donjon, though the most spectacular castles had up to four great keeps. Beautiful gardens and pools in the interior of the castle created a feeling of tranquility for the daimyo and his samurai. Unity in Japan meant that the great castles shifted from citadels of defense to commercial hubs. As outposts of the Bakufu, they became centers of government administration. Lesser samurai lived at the castle, now enforcing edicts instead of storming castles. Towns began to grow around the castles, populated by artisans and merchants who served the needs of the castle samurai. Travel demanded by the sankinkotai system created a need for inns, restaurants, stables, and stores along the routes between Edo and the provincial castles. A series of towns grew up along the system of roads connecting the provincial castles. A series of towns grew up along the system of roads connecting the castle towns. Services provided in these towns expanded the role of urban life. Craftsmen were needed to erect and repair the buildings of new cities. Artisans created furnishings, food had to be provided, and the samurai needed constant maintenance of their weapons, armor, and horses. Merchants and artisans flocked to these commercial centers, attracted by the concentration of travelers and garrisoned samurai. By the end of the Tokugawa period, these merchant and artisan townspeople, called chonin, supplanted the samurai as leaders in society because of the tremendous wealth they amassed. Population growth coupled with urban growth simulated commercial expansion. The population of Japan grew from about 18 million c. 1600 to near 26 million a century later. By the eighteenth century, there were nearly 40 castle towns of at least 10,000 people. As the seat of the Bakufu and home of the daimyo’s families, Edo swelled to nearly a million inhabitants. Osaka became chief port and commercial center, with a population of 400,000. Kyoto remained the cultural center as home of the Emperor, with a population of 350,000. Merchants and artisans flourished as these urban centers created markets for their products and services. Though the samurai were officially the highest-ranking class, merchants and artisans became the wealthiest segment of society. Legally barred from becoming samurai, the newly rich townspeople created a separate world of urban pastimes called ukiyoe (“floating world”). The ukiyoe’s frivolous life of wrestling matches, and gambling halls, rowdy Kabuki theaters, and lavish restaurants was frowned upon by the samurai. Yet as castle towns and roadside cities grew, and chonin acquired more wealth, the Bakufu was helpless to regulate the ukiyoe or the life of the chonin.