True Grit , Or How

Sights Denim Makes

Money in Dirty Jeans

--As Fashion Goes Grungier,

The Company Has a Blast;

Ah, Grease-Monkey Chic

By Rebecca Quick

10/12/1999

The Wall Street Journal

Page A1

(Copyright (c) 1999, Dow Jones & Company, Inc.)

HENDERSON, Ky. -- Tim Hazel, a 23-year-old with bleached-blond hair, a goatee

and five earrings lining his left ear, gazes thoughtfully at a pair of brand new blue

jeans. Then he gets down to work, savagely grinding sandpaper across the thighs

and knees.

With swift strokes, he creates "whiskers" (crease lines near the crotch), "crumples"

(three-dimensional whiskers, usually added at the back of the knee) and tears up the

hems, waist and fly. By the time he's done, the pants look like they've been worn by

an urban skateboarder who spends most of his time skidding in his jeans across the

concrete jungle.

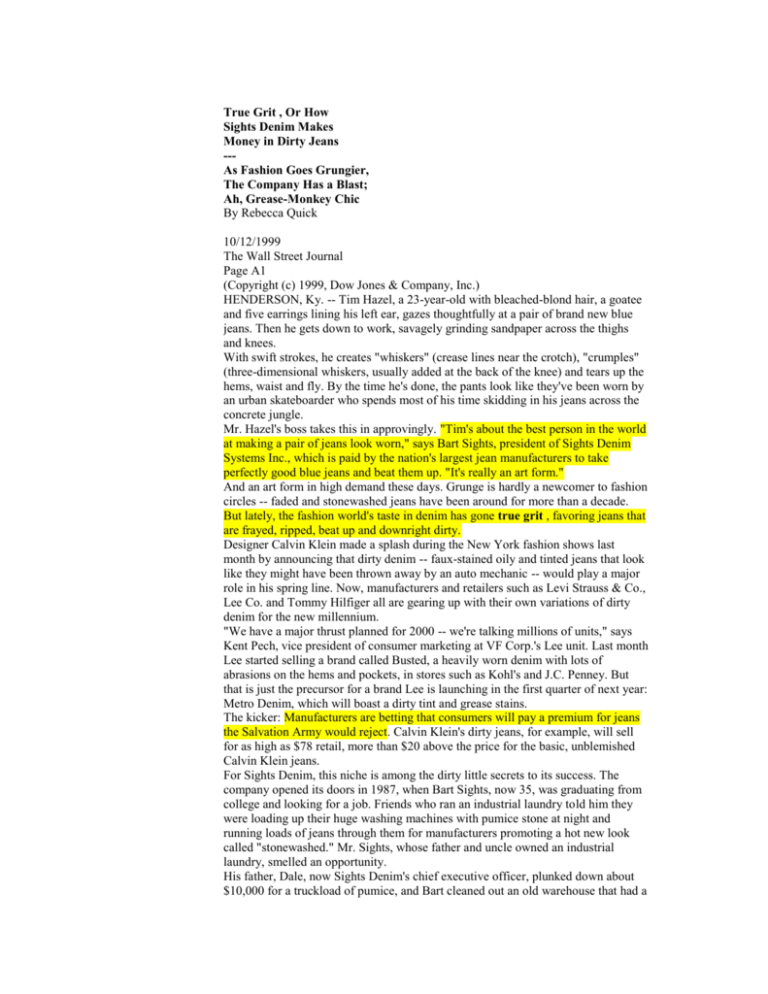

Mr. Hazel's boss takes this in approvingly. "Tim's about the best person in the world

at making a pair of jeans look worn," says Bart Sights, president of Sights Denim

Systems Inc., which is paid by the nation's largest jean manufacturers to take

perfectly good blue jeans and beat them up. "It's really an art form."

And an art form in high demand these days. Grunge is hardly a newcomer to fashion

circles -- faded and stonewashed jeans have been around for more than a decade.

But lately, the fashion world's taste in denim has gone true grit , favoring jeans that

are frayed, ripped, beat up and downright dirty.

Designer Calvin Klein made a splash during the New York fashion shows last

month by announcing that dirty denim -- faux-stained oily and tinted jeans that look

like they might have been thrown away by an auto mechanic -- would play a major

role in his spring line. Now, manufacturers and retailers such as Levi Strauss & Co.,

Lee Co. and Tommy Hilfiger all are gearing up with their own variations of dirty

denim for the new millennium.

"We have a major thrust planned for 2000 -- we're talking millions of units," says

Kent Pech, vice president of consumer marketing at VF Corp.'s Lee unit. Last month

Lee started selling a brand called Busted, a heavily worn denim with lots of

abrasions on the hems and pockets, in stores such as Kohl's and J.C. Penney. But

that is just the precursor for a brand Lee is launching in the first quarter of next year:

Metro Denim, which will boast a dirty tint and grease stains.

The kicker: Manufacturers are betting that consumers will pay a premium for jeans

the Salvation Army would reject. Calvin Klein's dirty jeans, for example, will sell

for as high as $78 retail, more than $20 above the price for the basic, unblemished

Calvin Klein jeans.

For Sights Denim, this niche is among the dirty little secrets to its success. The

company opened its doors in 1987, when Bart Sights, now 35, was graduating from

college and looking for a job. Friends who ran an industrial laundry told him they

were loading up their huge washing machines with pumice stone at night and

running loads of jeans through them for manufacturers promoting a hot new look

called "stonewashed." Mr. Sights, whose father and uncle owned an industrial

laundry, smelled an opportunity.

His father, Dale, now Sights Denim's chief executive officer, plunked down about

$10,000 for a truckload of pumice, and Bart cleaned out an old warehouse that had a

big industrial washer and dryer left in it. At first, business came in dribs and drabs;

then, later that year, children's clothes maker OshKosh B'Gosh Inc. signed up as a

regular customer. Soon, Sights had 400 employees custom-washing more than

100,000 pairs of jeans a week.

Since then, much of what is called the "finished wash" business has moved to

cheaper labor markets overseas or in Mexico. But closely held Sights has kept

chugging away, mostly because it early on recognized the lucrative worn-and-soiled

jeans niche. Of the 150,000 pieces of clothing Sights processes weekly, about

90,000 of them are permanently dirtied or frayed in some way. "We knew we had to

differentiate ourselves to survive," Bart says.

Devon Burt, creative director at Levi Strauss, calls Bart Sights "somewhat of an

industry legend." He adds, "Ten years ago, you would've never thought there would

have been someone like him, whose expertise is destroying denim."

To help hang on to its niche, Sights Denim designs its own styles, which it then

pitches to manufacturers and mills. Flea markets around the world provide

inspiration. Mr. Sights shows off a crumpled, camel-colored French worker's jacket

he unearthed browsing clothing cast-offs in Los Angeles not long ago. "It's a real

find," he says.

He is thinking about cloning the jacket; the trick will be to age buttons to give them

the worn look of the originals, and replicate the threadbare look and softly soiled

patterns in the fabric (skipping the hay he found in the pockets). Mr. Sights only

paid $40 for the jacket but "if someone had put the work into making it look that

old, it would have cost several hundred dollars," he explains.

The heart of the plant is Sights Denim's Abrasion Center, a warehouse specially

designed to rip up and despoil as many perfectly good pairs of pants as possible.

Visitors are confronted by a dark gray cloud billowing through the warehouse, the

gritty fallout of continuous sandblasting operations that pelt jeans with abrasive

aluminum oxide. Two shifts of workers keep the jeans lines running from 7 a.m. to

midnight, five days a week.

About 20 hand-scraping stations line one side of the warehouse. There, workers

apply sandpaper in carefully devised stroking patterns to each pair of jeans. The

patterns, which are devised by Mr. Hazel and then taught to the rest of the

handscrapers, take anywhere from two minutes to 32 minutes to apply, depending

on the severity of the abrasions.

In another corner, about 15 workers wield a toothbrush-shaped whirring tool called a

Dremel sander. Each disfigures jeans in a different way before passing them on; one

worker tears up waist bands, the next rips up back pockets, the next rips open the

hem on a pant leg, and so on.

The artistic heart of the Abrasion Center are eight sandblasting booths. Blasters,

wearing red helmets, striped "spacesuits" and breathing oxygen from a hose, attack

jeans with a fire hose that shoots out aluminum oxide under about 150 pounds of

pressure. On a good day, an experienced blaster can "global-blast" up to 600 pairs of

jeans-that is, scour every inch of every pair to give a totally worn look. If the order

is for "local blasting"simply mauling the knees and seats of jeans-blasters can often

manage 1,000 pairs a shift.

The master among blasters is Paul White, a 26-year-old who has worked for Sights

Denim for six years. He started out as a recycler, sweeping up aluminum-oxide grit

used for blasting, plus refilling piles of jeans for each of the sandblasters. A

coincidence led to a promotion: Bart Sights's wife was one of Mr. White's teachers

in high school, and she remembered that Mr. White liked to draw. "One day they

came to me and asked if I could still draw, because blasting is like being an artist

drawing on jeans," says Mr. White.

When friends question why ravaged jeans cost so much more than an unblemished

pair, Mr. White says they ought to come spend a day with him in the noise and grit

of his booth. "It's just a whole lot of work," he says. Besides, jean connoisseurs

understand that, these days, brand new is old-hat. "Sandblasting is a necessity now,

like an airbag in a car," Mr. White adds. "If you don't have it, it's like, you're not in."

Sanding and blasting is used to age and weather jeans; it is then left to a

sophisticated machine-washing operation to add the other necessary elements -- tints

that resemble grease, oil and various kinds and colors of dirt. Sometimes, when the

object is to make jeans that look like the kind your mother would put in a bag and

toss in the garbage, matters get a bit confusing. Not long ago, Sights quality-control

inspectors came upon a batch of pants so despicably soiled that they thought the

laundry had honestly messed up. So they sent them back for a proper washing.

But it was no mistake, says Donnie Harrison, head of the company's inspection

plant. "After a little research, we determined that's how Levi's had ordered them."

(See related letter: "Letters to the Editor: The Term `Rag Trade' Gains Real

Meaning" -- WSJ Oct. 28, 1999)

(See related letter: "Letters to the Editor: Let Them Wear Grunge" -- WSJ Nov. 3,

1999)

Copyright © 1999 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.