evolutionary perspectives on business and ethics

advertisement

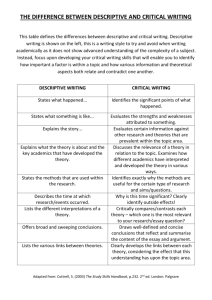

THE MODERN CORPORATION AS A COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEM: SCIENTIFIC AND MORAL IMPLICATIONS Ronald F. White, Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy, College of Mount St. Joseph ABSTRACT Scholarly research into nature of the corporation and business ethics is currently occupied by the “Nexus-of-Contracts theory.” However, as evolutionary theory worms its way into our theoretical understanding of human social organization, longstanding assumptions concerning the nature of Truth and Value have come under fire. Throughout the twentieth century, Darwinian Revolution has been reshaping our theoretical beliefs concerning the nature of modern corporations, corporate management, and business ethics. One of the more recent focal points of this “revolution” has been “Complex Adaptive Systems Theory” or CAS. The question, therefore, arises to what degree CAS elucidates the theoretical issues raised by the prevailing orthodoxy, the Nexus-ofContracts Theory. In this presentation I will explore the descriptive (scientific) and prescriptive (moral) dimensions of both the Nexus-of Contracts Theory and CAS and the implications for the Modern Corporation, management, and business ethics. CORPORATIONS: DESCRIPTIVE AND PRESCRIPTIVE DIMENSIONS Before we get too far, it’s important to set the epistemological stage. Human inquiry, according to the proponents of evolutionary epistemology, concerns the intergenerational process of asking questions and posing answers. They call the end products of inquiry beliefs or theories.1 There is a lot of disagreement among philosophers as to the precise purpose of scientific theories, but most will agree that theories or beliefs enable inquirers to explain, predict, and/or control natural phenomena. Most philosophers will also agree that there are two lines of inquiry: descriptive inquiry and prescriptive inquiry. Descriptive inquiry involves questions of “Truth” or “Fact,” while prescriptive inquiry explores questions of “Value” or “Goodness.” The epistemological relationship between the two has always been problematic. Since the twentieth-century, inquiry into the descriptive “nature” of the modern corporation and its management has been dominated by social scientists, primarily economists. The underlying assumption has been that scientific inquiry (as opposed to non-scientific inquiry) can discover this nature through the application of empirical and/or rational methodologies; that is, via the “Scientific Method.” Economic theorists have always been prone to a certain degree of heterodoxy and pluralism, as evidenced by the various schools of economic thought: Neoclassical School, Austrian School, Post-Keynesian School, Institutional School, and the Marxist School.2 The theories generated by these schools of thought reflect the kinds of questions and 1 answers engaged by their respective communities of inquirers. “Orthodoxy” today in economics is usually associated with adherence to neoclassical theory. However, the epistemic status of the other “schools of economic thought” is subject to debate. Orthodox economists, often argue that the “schools” actually reflect internal debate within the broad dictates of the neoclassical framework and that economists really agree on the basics of their science. On the other hand, the proponents of the various opposing “schools” often portray their own orientation as “revolutionary” and indicative of a whole new paradigm. All of this suggests that economists even disagree over whether or not they disagree. Evolutionarily, a certain degree of internal disagreement is regarded as a precondition for scientific innovation and advancement. The sociology of science can be messy at times. Despite this internal debate over the nature and extent of heterodoxy, there’s some general agreement that there are at least two alternative lines of descriptive inquiry (or paradigms) that have dominated the economic literature since the early twentieth century: the “neoclassical theory” and the “institutional theory.” Twentieth-century neoclassical economic theory is usually regarded as the progeny of the eighteenth-century “classical theorists,” led by Adam Smith. The main difference between the two is attributed to the “Marginalist Revolution” in economics championed by William Stanley Jevons, Leon Waltras, and Irving Fisher. In contrast, the “new institutional theory” (or evolutionary economic theory) is the progeny of the “institutional theory” as outlined by Thorsten Veblen, Wesley Mitchell, Walton Hamilton, and John Commons in the early 20th century. The most obvious bones of contention between the two alleged paradigms have to do with the nature of economic change, the use of equilibrium theory and Newtonian mathematical models (linear calculus), and how the paradigms deal with social relationships. But again, economists tend to disagree over the nature and extent of the differences between neoclassicism and institutionalism.3 And, that there are also important differences between old institutional economics, new institutional economics, and their relationship to the classical and neoclassical frameworks.4 So much of the descriptive debate between neoclassicism and institutionalism has been over the nature of “economic change” and the larger question of whether the human sciences should be modeled after a Newtonian Worldview, based on physics; or, a Darwinian Worldview, based in biology; and, whether the human sciences are about individual behavior (individualism) or group behavior (collectivism). Neoclassicists focus on the decision-making strategies of individual entrepreneurs, and institutionalists tend to focus on collective behavior manifest in the organizational structure of a society, or, institutions (E.g. conventions, routines, and procedures). In general, the so-called Darwinian worldview, embraces change as the natural state of economic reality (process-based ontology); irreducible, infinite complexity; and the emergence of properties of the system that the separate parts do not have.5 The Darwinian influence upon scientific inquiry was clearly evident in early twentiethcentury physics via quantum physics and relativity; in philosophy via Peirce’s pragmatism and Karl Popper’s evolutionary epistemology. Beginning in the 1970s, the Darwinism influenced psychology and the social sciences via sociobiology, however it’s more lasting impact came in the 1980s. In twentieth-century economics, Darwinism was clearly evident Austrian economics thought, via F.A. Hayek; and Joseph Schmpeter, 2 whose evolutionary insights later contributed to “new institutional economics” or “evolutionary economics” as described by Nelson and Winter.6 In the early twentieth century, the descriptive theory of the corporation (or “the firm”) was clearly dominated by, neoclassical economic theory and the Newtonian worldview, which really “had no place for the entity called the firm.”7 Or to be more precise, the firm was treated as a “unitary agent: the personification of the entrepreneur and firm behavior is equated with the behavior of the entrepreneur.8 It is probably fair to say that the much of the current interest in extending the Darwinian Worldview into economics and management theory can be attributed to the influence of mainstream institutional economists such as Coase and Williamson. Since 1984, the Santa Fe Institute, a private, non-profit, multidisciplinary research and education center, has been especially influential in its defense of CAS and institutional economics as seen through the lens of Complex Systems Theory. Now it is important to acknowledge that many neoclassical economic theorists do not accept this Newtonian-Darwinian distinction and the characterization that they are stalwart Newtonian positivists resistant to evolutionary change. After all, economic theory was, indeed, evolutionary long before Darwin ever stepped foot on the Beagle. EFFICIENT VS. MORAL MANAGEMENT OF CORPORATIONS One of the more obvious empirical “facts” that underlie the nature of the modern corporation is that it is created and “managed” by human beings. Of course, knowledge of how to manage a corporation is contingent upon descriptive knowledge of the “ends” or “purposes” that a corporation is intended to serve; and knowledge of the means by which managers can realize these ends. In the United States, orthodox economic theory implied management in the service of the “efficiency” of the means of enriching the entrepreneur. In the 1920s, Scientific Management or “Taylorism,” integrated the Newtonian scientific worldview with management theory by treating the modern corporation as a cash machine subject to mechanical laws of efficiency. Management was, was seen as a form of engineering and therefore subject to the mechanical laws of nature. Good corporations survive market competition because good managers armed with scientifically-based engineering skills maintain or increase efficiency. Bad corporations are inefficient corporations that are led into oblivion by unskilled managers. Ethicists, however, must also explore not only efficiency, but also the morality of ends and the morality of means. Hence, much of the descriptive and prescriptive analysis of corporations can be summarized in terms of three basic questions: 1. Whose ends (or interests) are in fact served by corporate managers? (E.g.: stockholders, consumers, employees, managers, suppliers, etc.) AND, whose ends (or interests) ought to be served by corporate managers? 2. By what means can managers employ in order to efficiently realize these stated ends (or interests) AND, what means can managers employ within the bounds of morality? 3 3. What role does government in fact play in the realization of these various corporate ends AND, what role government “ought” to play in this process. In terms of the management of corporations worldwide, contemporary scholars have identified three alternative roles for managers: Managers as Economic Actors, or agents of shareholders; Managers as Trustees, or agents of stakeholders; and Managers as Quasi-Public Servants, or agents of society.9 The concept of a “good manager,” therefore, is contingent upon how well he/she fulfills obligations to shareholders, stakeholders, and/or society. But despite the idealistic ruminations of various “win-win” strategies, in the real world, what is “good” for shareholders may or may not be “good” for other stakeholders, and/or society; what’s “good” for stakeholders may or may not be “good” for stockholders and society; and, what’s “good” for society as a whole, may or may not be “good” for stakeholders and stockholders. Any theory of the corporation must take into account the reality of “win-win,” “win-lose,” and “lose-lose” outcomes. FACTS, VALUES, AND CORPORATIONS One of the most perplexing questions in the history of philosophy has to do with the relationship between descriptive “facts” and prescriptive moral “values” (or, the “is” and the “ought.”). Many eighteenth-century scientists (including Adam Smith) were “natural law theorists” that believed that moral values could be deduced from scientific facts. However, Plato, David Hume, Kant, and a raft of 20th century philosophers, most notably, G.E. Moore argued that facts (how humans act) and moral values (how humans ought to act) are incommensurable. They argued that any attempt by natural law theorists to close the “is-ought gap” and derive “values” from “facts” commits the “naturalistic fallacy.” So, at least in terms of the history of philosophy we must acknowledge that the logical relationship between “facts” and “values” has been problematic and that any theory of the corporation that tries to blurs that line runs the risk of being accused of committing the “naturalistic fallacy.” The moral inquiry in the philosophical tradition has always been steeped in theoretical pluralism. Today, most philosophers agree that there are three competing models of moral theories. There are deontological theories (divine command theory and egalitarian and libertarian social contract theory), which construe morality in terms of rights and duties; teleological theories, which construe morality in terms of the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain (egoism and utilitarianism); and virtue-based theories, which see morality in terms of the pursuit of excellence. Since the 1970s, under the influence of John Rawls’ Robert Nozick’s libertarian theory, most moral philosophers have embraced one of the two deontological models. However, utilitarianism and virtue based ethics still attract many adherents. Proponents of contemporary evolutionary ethics also seek to close the “is-ought gap,” but tend to gravitate toward utilitarianism10 and virtue based theories.11 In terms of naturalism, there may be compelling philosophical reasons for preferring utilitarian and virtue based theories over deontology. In recent years, the communitarian movement has offered a broad-based critique of the foundations of deontological theory. Communitarians basically argue that the two opposing deontological theories that constitute Western Liberalism are not universal moral theories, but political theories embedded in Western democratic ideology. 4 Therefore, neither egalitarianism nor libertarianism can distinguish between the political “Right” and the moral “Good.” Some scholars also argue that Rawls and Nozick’s rightsbased theories fail differentiate between “moral persons,” “legal persons,” and “political persons.”12 So there are two basic kinds of questions we can ask about the modern corporation and its management: “What is a corporation?” and “What is a “good corporation?” Orthodoxy in business ethics strives to close the “is-ought gap” with a single universal theory that is both descriptive and prescriptive. Critics of this strategy tend to uphold the “is-ought gap” and “fact-value incommensurability.” NEXUS-OF-CONTRACTS THEORY Orthodoxy in business management and business ethics is currently occupied by a deontological “Nexus-of-Contracts Theory,” whereby: “each constituency or stakeholder group bargains with the firm over a set of rights that will protect the firm specific assets that it makes available for production.”13 Within that broad framework, two opposing sub-theories can be identified and contrasted: “stockholder theory” (which is grounded in libertarianism) and “stakeholder theory” (which is grounded in egalitarianism). Boatright convincingly argues that the debate between stockholder and stakeholder theories is elucidated by this more general “Nexus-of Contracts” approach and that stockholder theory wins that head-to-head competition. Let’s start with a few general observations on the “Nexus-of Contracts Theory.” First of all, the theory is based on the basic Enlightenment concept of a “social contract,” which builds on the idea that we can forge social theory based on how, rational, self interested, individuals would, hypothetically, bargain with one another in the absence of coercive forces. In short, under certain objective circumstances, rational self-interested agents will chose cooperation over predation. The Nexus-of-Contracts Theory claims to be both descriptive and prescriptive. It is descriptive in so far as it accurately depicts the nature of the corporation. Indeed, the most casual empirical observation reveals that corporations are, in fact, comprised of groups of interacting human beings (“bargaining”) stakeholders (stockholders, consumers, managers, employees, consumers etc.). It is also evident that these relationships are shaped by both the “invisible hand” of the market and the “visible hand” of corporate law as enforced by sovereign governments. The “Nexus-of-Contracts theory holds that corporations are actually “legal fictions” that are “socially constructed” in order to minimize “contracting costs” associated with cooperatively negotiating the conflicting interests of contractors, most notably the cost of monitoring compliance.14 But it is also empirically evident that, worldwide, corporate laws vary between the “microsocial contracts” of national or state governments. This, of course, suggests a degree of descriptive relativism.15 Therefore, one of the puzzles facing the Nexus-ofContracts Theory is whether business ethics is hopelessly mired in cultural relativism or whether there are, at least some, “hypernorms” that constitute the basis for universal human rights.16 Now in order for the Nexus-of Contracts Theory to be both descriptive and prescriptive (or normative) it must do more than explain how the various classes of stakeholders (stockholders, consumers, managers, employees, consumers etc.) in fact 5 bargain (or would bargain) in the real world within various environments. It must also prescribe “moral and/or legal rules” that govern how stakeholders ought to bargain, prescribe impartial rules dictating whose interests “ought” to prevail under various competitive conditions, and prescribe what role markets and national governments, and international governing bodies ought to play in this process. All human societies enforce prescriptions through both legality (laws enforced by the coercive power of government) and through morality (rules enforced by tradition, convention, and/or social learning). For most philosophers, there are important distinctions between “legality” and “morality,” and between “legal rights” and “moral rights.” Much of this debate focuses on the use of “coercion” in the enforcement of legal and/or moral rules. Kant, for example, distinguished between a “good citizen” (who obeys the law out of fear of getting caught) and a “good person” (who obeys the law out of love and respect for the law itself). So much of the distinction between “legality” and “morality” hinges on the use of the coercive power of the state. Both the egalitarian and libertarian wings of Western liberalism take the view that there at least some universal moral rules that all rational contractors will uphold in the absence of coercion. The most serious challenges to a naturalistic closure of the “is-ought gap” has come from a motley crew of philosophical realists. Some realists point out that, empirically speaking, human beings that occupy the so called “real world” do not always act rationally, do not always act out of individual self-interest, do not always cooperate, rarely act out of impartiality, and often do not make decisions in the absence of coercion. Moreover, human beings do not always know the Truth and if they do know the Truth, they often conceal it or distort in order to advance self-interest. Therefore, at least on the surface rationality, individuality, self-interest, free will, impartiality, and Truth appear to be more prescriptive than descriptive. Other realists point out that there is a lot of perfectly natural human behavior that runs counter to our most basic moral intuitions: predation of the weak by the strong, male violence, war, ethnocentricity etc. But the most daunting challenge to closing the “is-ought gap” is the “fact” that when human beings do “naturally” pursue rational self-interest, they all too often do it at the expense of the rational self-interest of others. Hence, it may be perfectly “natural” for human beings to violate contractual obligations, and reconstruct the Truth out of self-interest. But that doesn’t mean that this behavior is good! The classical and neoclassical economic traditions argue that the “natural” pursuit of rational self-interested atomic individuals axiomatically leads to the social good. However, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and the realists emphasized the essential role of coercive legality as a bulwark against the unbridled pursuit of self-interest by predatory, powerful individuals and groups. The Nexus-of-Contracts approach takes realism seriously by emphasizing legality, but can it also deal with morality? In the real world, bargaining position between self-interested constituencies is naturally determined on the basis of an unequal distribution of “power,” which is to say that it takes place under conditions of “unequal liberty.” Hence, in the real corporate world there are times and places where the interests of power-wielding stockholders prevail over the interest of employees and managers (CEO’s); there are times and places where power-wielding unionized employees prevail over the interests of stockholders and CEO’s; and there are times and places where the interests of power-wielding CEO’s prevail over the interests of both stockholders and employees. If a manager hopes to 6 redistribute the prevailing distribution of power he/she must do so from a position of superior power. The key here is that there are important differences between “Knowledge” and “Power.” In terms of ethics, there is a big difference between “Knowing” what’s right and “Doing” what’s right. A close reading of Machiavelli suggests that bargaining in the real world is not a simple matter to be resolved based on linear calculus. Distributions of power are invariably influenced by not only background institutions, information (and misinformation), and the aggregated (and often irrational) decisions of other selfinterested stakeholders, but also by raw chance, or emergence. In terms of management theory, this makes short-term planning very difficult and long-term corporate planning an exercise in futility wrought with unanticipated consequences. Evolutionarily-based political theorists, including Machiavelli, emphasize the reality of chance variation (emergence) and its implications for the long-term and short-term management of nations and corporations. Moreover, according to Machiavellian theory, any manager that hopes to maintain power over other self-interested stakeholders, and preserve the corporation, would have to resist the lure of self-interest and partiality and manage the corporation as a social utilitarian. Of course, any social utilitarian must not only possess “knowledge” of what constitutes the “public good” (over the short term and/or the long term) and “knowledge” of the means to achieve it; but also the “power” to alter the status quo. Moral intervention and the upending of the status quo, therefore, imply both Knowledge of a more justified distribution and the Power to execute that distributional scheme. So, if we expect managers, stockholders, consumers, managers, and/or employees to cooperate and transcend their own atomic (or collective) self-interest, and pursue the larger “social good” they’ll need both knowledge and power. Any leader that aspires to manipulate or control the relations of power between self-interested stakeholders will need to possess not only knowledge of ends and means, but also possess superior firepower, and the willingness to occasionally utilize that coercive power (or as Machiavelli put it: “enter into evil”) and employ immoral means in order to serve the greater good and insure the survival of the corporation or the nation. However, the most serious lacunae in the Machiavellian formula is that evolutionary biology casts doubt on whether we can reasonably expect to cultivate altruistic utilitarian behavior in corporate and political leaders, in the absence of coercive governmental institutions. In short, morality alone may not be an efficient bulwark against corporate corruption among powerful leaders. So any contractarian prescriptive theory of the modern corporation must account for the realities associated with bargaining over “conflicts of interest” when there is natural inequality of bargaining power between the various stakeholders via a rightsbased moral theory. Although “real world” managers (and other stakeholders) are described as natural egoists in pursuit of self-interest, Machiavellians prescribe that managers “ought” to be utilitarians that serve the interests of the corporation over their own personal self interest. But moral prescriptions are notoriously weak in the absence legal prescriptions backed by coercive force. As, the Enron Scandal graphically illustrates, in the real world, the most powerful corporate stakeholders (in Enron’s case it was upper management) will “naturally” pursue self-interest at the expense of the least advantaged stakeholders unless they are constrained by legal sanctions enforced by “well armed” external private regulators (auditors) and public regulators (SEC). Hence, the 7 Nexus-of-Contracts Theory must take into account the ever-changing power relationships between contracting stakeholders and government. STOCKHOLDERS AND STAKEHOLDERS Within the contractual constraints set by the Nexus-of Contracts framework there are two opposing theories that offer different strategies for dealing with “conflicts of interest” and “natural inequality:” stockholder theory and stakeholder theory. Stockholder theory states that the best (most efficient) way to serve the interests of all stakeholders is to always manage the corporation to serve the interests of stockholders. A corollary to the theory is that the interests of the other stakeholders are morally relevant, but are best met via the impersonal “invisible hand” of the market. All real world contractors go to the bargaining table armed and/or burdened with natural inequalities. Hence, we have the political question concerning the role of government in mediating the process. Based on stockholder theory, and libertarian ideology, all rights are “negative rights” in the sense that bargainers are guaranteed the equal right to bargain, but there can be no “positive rights” guaranteeing that any one stakeholder or stakeholder group will emerge victorious as a result of the competitive process. According to libertarian stockholder theory, government ought to be “impartial” or “neutral” in the determination of winners and losers. The primary purpose of government, therefore, is to simply enforce contracts between rational self-interested bargainers. This includes providing a legal framework that includes the monitoring and enforcement of impartial rules of fair play. From the standpoint of stockholder theory, the challenge is how to manage corporations in such a way that the pursuit of self-interest by stockholders benefits the other stakeholders. The traditional natural law approach suggests that Mother Nature prefers equilibrium, which tends to “floats all boats.” The stockholder theory is “naturalistic” in the sense that it is based on “reciprocal altruism,” which if left to its own devices can settle into equilibrium; whereas, utilitarianism requires a degree of otherworldly “ideal altruism.” Therefore, stockholder theory avoids the problem of how to cultivate ideal altruism (utilitarianism) into a system naturally populated with selfinterested bargainers. But it also requires a bit of altruism. Not on the part of the contractors themselves, but on the part of the governmental institutions responsible for maintaining free market competition and monitoring corporations to insure contractual compliance. Edward Freeman’s “Stakeholder Theory” is management to serve the interests of the multiple constituencies that ‘have a stake in’ management decisions including: stockholders, employees, customers, managers, suppliers, and the local community.17 Stakeholder theory observes that serving the interests of stockholders does not always maximize the interests of the other stakeholders, and that managers (and/or government) must at least occasionally abandon impartiality and intervene on behalf of the “leastadvantaged” stakeholders, or those that find themselves bargaining under conditions of unequal liberty. Hence, there are at least some “positive rights” associated with stakeholder theory. A recent book by Robert Phillips suggests that stakeholder theory implies a Rawlsian moral foundation.18 The argument against Rawls’ account of the prescriptive 8 bargaining process as the pursuit of an “overlapping consensus” conducted under a hypothetical “veil of ignorance” is that it’s not clear how real world bargainers could go about bargaining under that veil, given that in the real world we all come to the bargaining table armed with our “natural advantages” and/or burdened with our “natural disadvantages.” Again, in the real world stakeholder theory must provide an explanation as to why the “most advantaged” would bargain with the “least advantaged.” One typical Rawlsian response is that rational, self-interested bargainers would sacrifice their short-term “advantages” for long-term “security.” After all, even Donald Trump gets sick, and will eventually suffer the infirmities of old age. But when an agreement is forged between the “advantaged” and “least advantaged,” there is always the question of whether the contractors can “Trust” each other to keep their promises. For a realist, this uncertainty once again underscores the need for external monitoring of contracts by government and the use of coercive force to punish non-compliance. Of course, then the bargainers have to idealistically “Trust” the impartiality of government. So although, the Nexus-ofContracts Theory embraces realism’s naturalistic critique of corporate altruism, it invariably raises the question: “Who is monitoring the monitors?” In the end, Nexus-of Contracts Theory ultimately requires trustworthy international monitors, or governmental altruism. Finally, it is important to point out that all collective moral and legal decisionmaking involves leaders and followers, which raises the problems related to “agency relationships,” and therefore requires “agency theory.” In its simplest terms, agency raises the question is how corporations and the nexus of stakeholders can develop strategies that induce self-interested “agents” (such as CEOs) to act in the interest of “principals” (such as stockholders). Stockholder theorists try to arrange incentives in order to align the interests of agents with principles. Stakeholder theorists tend to rely heavily on the coercive power of government to align those interests. Of course, the main point of contention between the stockholder and stakeholder theories is how government ought to manage legality and morality in order to minimize the ill-effects of coercive, predatory, self-interested corporate behavior. I have argued that the Nexus of Contracts Theory, in both the stockholder and stakeholder traditions, require altruistic governmental institutions, although stockholder theory requires less because government is expected to do less. Boatright argues that the descriptive claims made by stockholder and stakeholder theory are empirical matters that can be resolved based on scientific methods within the larger context of the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory. I’ll simply suggest that Complex Management theory elucidates Nexus-of-Contracts Theory, but it does not resolve the “stockholder-stakeholder debate.” It simply dissolves it, by acknowledging the descriptive fact that both power and knowledge (or information) evolve over time relative to an enormously complex and rapidly evolving social and intellectual environment. So although, stockholder theory still reins supreme in the United States, given the complexities raised by the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory, there is no guarantee that it will, in fact, maintain its status as orthodoxy, nor can there be any moral basis for arguing that it “ought” to prevail in the future or that it “ought” be adopted by other socio-political environments. 9 In sum, realism identifies five theoretical puzzles that the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory must address: the inequality of bargaining power, the relationship between “Power” and “Knowledge,” the “is-ought gap,” the distinction between “legality and morality,” and the alignment of the interests of “agents and principles.” But does CAS shed any light on these issues? COMPLEX MANAGEMENT THEORY Well, what exactly does “Complex Management Theory” say about all this, and does it elucidate the five problems stated above? First of all, management theory is a lot like economic theory in the sense that there both bona fide competing paradigms and non-scientific pseudo-scientific theories. The difference between the two is not always clear. The Internet is a prolific source of innovation, which includes a lot of quackery. The primary question here is whether CAS represents legitimate science or mere quackery. The short answer is that much of the CAS agenda is not all that controversial and has already been introduced into economic debate via its various “schools of thought,” most notably, Austrian Economics and its approach to management. “Complex Management Theory” is the extension of “Complex Adaptive Systems Theory” to management theory and economic theory. Admittedly, there is not an awful lot of consensus among CAS theorists, although the basic principles of CAS have been more-or-less crystallized in the recent writings of scientists associated with the Santa Fe Institute, including Brian Arthur, David Stark, and Kenneth Arrow. It is also important to note that other scholars have opened similar lines of evolutionarily-based research, most notably Robert Axelrod, at the University of Michigan, who has examined the bargaining process via “game theory” as an “iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma.”19 It is also significant that many of the descriptive claims of the CAS agenda were raised in the twentieth century within the context of the debate between “neoclassical economics” and “new institutional economics” or “evolutionary economics.” What is unique about CAS is its application of “systems theory” to the real world problems of management. According to its proponents, systems theory provides a theoretical framework for analyzing complex, disparate phenomena that have been regarded as incommensurable and associated with different disciplines, such as star systems, ecological systems, social systems, language systems, and economic systems. Systems theory is often referred to as the most recent “Theory of Everything,” or T.O.E. There is still a lot of variation in the terminology, however most theorists still distinguish between: relatively simple closed (Newtonian) systems and complex open (Darwinian) systems. Brian Arthur offers the following summary of the critique of orthodoxy offered by institutional economists and CAS: “Economic agents, be they banks, consumers, firms or investors, continually adjust their market moves, buying decisions, prices, and forecasts to the situation these moves or decisions create. But unlike ions in a spin glass which always react in a simple way to their local magnetic field, economic “elements” –human agents- react with strategy and forethought by considering outcomes that might 10 result as a consequence of behavior they might undertake. This adds a layer of complication to economics not experienced in the natural sciences. Conventional economic theory chooses not to study the unfolding of the patterns its agents create, but rather to simplify its questions in order to seek analytical solutions.”20 The common denominator between institutional economics and CAS is their portrayal of neoclassical economics as embracing an outdated Newtonian Worldview that has been more or less abandoned by most other lines of inquiry: including, physics, biology, psychology, and even philosophy. Therefore, it’s about time for economists to abandon that sinking ship. In terms of management theory CAS argues that managers cannot manage a complex real world corporation based on overly simplistic Newtonian economic models and agent-centered managerial theories. For evolutionarily based management, the most salient points of contention involve how chance variation and emergence shape the nature of information and the role of experts. If there is a single point of contention between Newtonian and Darwinian systems it is their opposing views on the nature of “chance.” Newtonians see chance as an epistemological problem, a reflection of our ignorance of the deterministic laws that govern complex phenomena. They insist that in the future, complexity will be simplified via reductionism and the illusions of chance and mysterious emergence will disappear. But Darwinians see chance and emergence as ontological realities, attributes of the real world that must be reflected in any complex system, including the T.O.E (Theory of Everything). Complex adaptive systems are neither “mechanical” nor “chaotic” but naturally poised on “the edge of chaos” “between two poles: two much order and too much chaos.”21 This means that all human knowledge, including corporate knowledge, is imminently fallible. From a Darwinian perspective, fallibility is not a sign of systemic weakness, but a prolific source of systemic innovation. This means that the traditional notion of “expert” as “philosopher-king must be revised. Expert corporate management, therefore, is not about wise and impartial “philosopher-kings” applying timeless axiomatic principles to a freeze-framed corporation. It’s about harnessing the natural principles of self-organization by allowing innovation to occur within the lower levels of the corporation and managing via “trial and error.” But again this is nothing new. Since the 1940s, F.A. Hayek and the Austrian school of economic thought have been touting self-organized systems theory and its implications for leadership. 22 One of the attractive features of systems theory in general is that it encourages inter-systemic analysis. CAS, therefore, applies to all complex systems including: biological systems, information systems, social systems, and economic systems. Here’s how some of the scholars at the Sante Fe Institute frame their theory. John Henry Holland outlined four properties (aggregation, nonlinearity, flows, and diversity) and three mechanisms (tagging, internal models, and building blocks) that outline the CAS agenda.23 John Henry Clippinger III gives the following description of those properties and mechanisms: 11 The properties identify the key formative characteristics of any self-organizing system. They represent those things that managers should look for, work on, and influence. Aggregation refers to the fact that collections or groupings display properties that are more than the sum of their parts. The property of nonlinearity is displayed when small increments of change can cause enormous unexpected threshold changes. Flows are webs or networks of interactions such as resources, orders, goods, capital, or people. Diversity is a measure of variety; in general, the more diverse and organization, the more fit and adaptable it is, up to the edge of chaos, beyond which too much diversity precludes the formation of order or organization. Techniques that managers can use to effect changes in the properties are the three mechanisms. Through these mechanisms managers can initiate sustainable self-organizing processes to achieve specific organizational and strategic goals. Tagging . . . refers to the naming, or labeling, of a thing or quality so as to give it certain significance or link it to action. Prices, job titles, reputations, and definitions of all kinds are tags. Internal models are simplified representations of the environment that anticipate future actions or events. Stereotypes are types of internal models that simplify complexity of the environment to anticipate specific behaviors. Building blocks are components that can be endlessly recombined to make new components or actions; think of the four proteins that make up all DNA . . .24 Without going into the details of CAS, the main issue whether a descriptive TOE (theory of everything) generate moral prescriptions? If systems theory can generate moral prescription across disciplines, we should be able to justify universal moral rules that all complex systems including: economic systems, political systems, legal systems, informational systems and even biological systems. NEXUS-OF-CONTRACTS THEORY, CAS, AND THE “IS-OUGHT GAP First of all, let’s reiterate that much of what CAS has to say about economics and leadership is neither new nor all that controversial. Much of the CAS agenda was introduced into economic thought during the twentieth century via institutional and Austrian economics. The main contribution of CAS seems to be the theoretical structure and vocabulary of complex systems theory. Nevertheless, I would argue that CAS really does elucidate the descriptive component of the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory. However, both the stockholder and stakeholder interpretations of the Nexus-of-Contracts approach require, impartial laws governing economic competition, impartial legislators serving the “public good,” and impartial enforcement of those laws. But in the real world, the persons and institutions that constitute economic environments are not, in fact, impartial. They are deliberately designed to advance the self-interest of competing stakeholders at various times in various places. Although CAS accepts self-interest as a reality, it also raises serious doubts concerning the efficiency of these “designs.” Moreover, in the real word, “agents” that represent groups of stakeholders that are unrestrained by legality may not necessarily serve the interests of their “principals.” This agency conundrum also applies to governmental officials acting as “agents” for the 12 “public good.” Therefore, Nexus-of -Contracts Theory requires altruistic CEOs, Chairmen of the Board, Union Presidents, Accountants, and governmental regulators. The basic problem with CAS is that it does not elucidate the prescriptive component of the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory. It certainly does go a long way toward explaining how legal institutions within and between nations are shaped by complex evolutionary forces. But CAS contributes little of substance to the closing of the “isought gap.” If the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory is to fulfill both its stated descriptive and prescriptive functions it must be able generate universal moral prescriptions that apply in the real world without relying on coercive force. If the Enron and WorldCom debacles are at all indicative of the prevailing balance of power in corporate America, it would appear that in recent years, one group of highly paid stakeholders (that is, upper management), has held power over other stakeholders and governmental regulators. However, based on CAS it is hard to argue that this particular distribution of power makes any “better” in the prescriptive sense than any other possible distribution. But this essay will not end on that sour note. There are two alternative conclusions. First, it may be the case that descriptive and prescriptive inquiry are, in fact, incommensurate and that the deontological Nexus-of-Contracts vision of closing the “isought gap” is simply untenable. I tend to lean toward this position. Or, second, it may be the case that the utilitarian and/or virtue-based moral theories might prove to be more compatible with evolutionary ethics and therefore, offer a more plausible strategy for closing the “is-ought gap.” CONCLUSION In this essay, I have argued that CAS management theory elucidates the descriptive dimension of the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory of the modern corporation. A consistent systems approach to the descriptive and prescriptive dimensions of the modern corporation implies that the same evolutionary principles that elucidate the descriptive nature of corporate institutions must also elucidate governmental institutions. But does not CAS really elucidate the prescriptive dimension. I have suggested that there are really four theoretical puzzles that continue to haunt evolutionary approaches the business ethics, and indeed ethics in general: “is v. ought,” “legality v. morality,” “power v. knowledge” and “agents v. principles. I would argue that CAS does shed light on the descriptive inequality of bargaining power between stockholders, stakeholders, and society; the descriptive variation and relativity between microsocial moral and legal systems; and the descriptive inefficiency of moral sanctions in comparison to legal sanctions. But it cannot morally justify any one distribution of power. In short, CAS is morally neutral. In sum, the Nexus-of-Contracts theory explicated in terms of Complex Adaptive Systems Theory appears to be promising as a descriptive theory of the nature of the modern corporation, but it is not a very promising as a prescriptive theory. In the real world, evolution is a messy process that may not “float all boats” at all times and in all places. The vision of deducing moral rules from the laws of nature remains problematic. 13 REFERENCES See: Charles Sanders Peirce, “The Fixation of Belief; ” and Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations. David L. Prychitko, ed. Why Economists Disagree: An Introduction to Alternative Schools of Thought (Albany: SUNY Press, 1998) pp. 1-13. 3 David Hamilton, Evolutionary Economics: A Study in Economic Thought (New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1991) p.9 4 David L. Prychitko, Why Economists Disagree: An Introduction to the Alternative Schools of Social Thought (Albany: SUNY Press, 1998) pp.156-160 5 Robert Axelrod, Harnessing Complexity: Organizational Implications of a Scientific Frontier (New York: Basic Books, 2000) p.15 6 Lars Magnusson, Evolutionary and Neo-Schumpeterian Approaches to Economics (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994) 7 Gunnar Eliasson, “The Theory of the Firm and the Theory of Economic Growth: An Essay on the Economics of Institutions, Competition, and the Capacity of the Political System to Cope with Unexpected Change” (in) Evolutionary and Neo-Schumpeterian Approaches to Economics (ed) Lars Magnusson (Boston: Kluwer Publishers, 1993). p.173. 8 Jack J. Vromen, Economic Evolution: An Enquiry into the Foundations of New Institutional Economics (London: Routledge, 1995) p. 41 9 John R. Boatright, Ethics and the Conduct of Business, 4th ed., (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003) p. 21 10 Peter Singer, A Darwinian Left: Politics, Evolution, and Cooperation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999). 11 Larry Arnhart, Darwinian Natural Right: the Biological Ethics of Human Nature (SUNY Press, 1998) and William D. Casebeer, Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003) 12 Rainer Forst, Contexts of Justice: Political Philosophy Beyond Liberalism and Communitarianism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002) pp. 283-292. 13 John Boatright, Contractors as Stakeholders: Reconciling Stakeholder Theory with the Nexus-of Contracts Firm” Journal of Banking and Finance 26 (2002) p. 1837 14 John R. Boatright, “Justifying the Role of Shareholder” (in) The Blackwell Guide to Business Ethics, ed. Norman Bowie (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002) pp. 40-42. 15 Thomas W. Dunfee and Thomas J. Donaldson, “Untangling the Corruption Knot: Global Bribery Viewed through the Lens of Integrative Social Contract Theory” (in) The Blackwell Guide to Business Ethics, ed. Norman Bowie (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002) p. 64. 16 Ibid p.66 17 Tom L. Beauchamp and Norman E. Bowie, Ethical Theory and Business, 6th edition (Prentice Hall: 2001). 18 Robert Phillips, Stakeholder Theory and Organizational Ethics (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2003) 19 Robert Axelrod, The Complexity of Cooperation: Agent-Based Models of Competition and Collaboration (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). 20 W. Brian Arthur, “Complexity and the Economy” Science Vol. 284 (April 2, 1999) p, 107 21 John Henry Clippinger III, ed. The Biology of Business: Decoding the Natural Laws of Enterprise (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1999) p.8. 22 See: F.A. Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948). 23 John Henry Holland, Hidden Order: How Adaptations Build Complexity (Massachusetts: AddisonWesley, 1995). 24 John Henry Clippinger III, ed. The Biology of Business: Decoding the Natural Laws of Enterprise (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1999) pp 10-11. 1 2 14 APPENDIX Perfect Information Imperfect Information All stakeholders must know their short-term and long-term interests, know how to advance those interests. All stakeholders must tell the truth. Stakeholders do not always know their short-term and longterm interests (Mistakes). Stakeholders do not always know how to advance their short-term and long-term interests. Stakeholders do not always know the Truth or tell the Truth. When stakeholders forge a contract they must clearly understand the terms of that contract (transparency). When stakeholders forge a contract all parties do not always clearly understand the terms of that contract. Language is not always transparent. Perfect Cooperation Imperfect Cooperation When there is a conflict of interest, powerful stakeholders must cooperate with less powerful stakeholders, and perhaps sacrifice their own interests for the interests of others. Stakeholders cooperate only if they believe that cooperation advances their own interests. (reciprocal altruism) When stakeholders forge a "contract" all stakeholders must keep their promise to abide by the conditions of the contract. "Agents" serve the interests of their "principles" only if their own interests coincide. Otherwise, they serve their own selfinterest. All "agents" (managers, union leaders, politicians etc. ) must serve the interests of their "principals" (stockholders, union members, electorate). Perfect Freedom Imperfect Freedom All stakeholders must have the freedom to accept or reject contract offers based on their own self-interest. Contract offers between powerful and less powerful stakeholders can be coercive. "Take it or leave it." 15 Imperfect CompetitionPerfect Competition Inefficient corporate governance forms will be weeded out by the invisible hand of the market (natural selection) under the competitive conditions of the bargaining process. But corporate law is forged within a social and political context and corporate law is often forged in in the interest of the most powerful stakeholders. Hence, both efficient and inefficient governance forms can be sustained by governmental interference in the market via legality (patents, licensing, credentialism, tax policy, tariffs, criminal justice system, cronyism etc.) Therefore, the invisible hand is often (if not invariably) thwarted by powerful stakeholders that manipulate the rules of the game via legality. So at any given time or place, governance forms are not a reflection of "fitness" but a reflection of "power or influence." 16