Generic import risk analysis (IRA) for uncooked chicken meat Issues

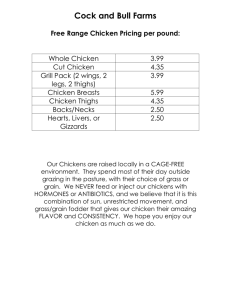

advertisement