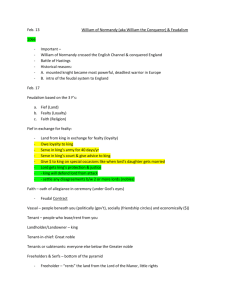

FEUDALISM

advertisement

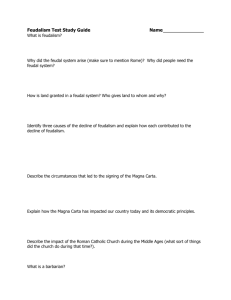

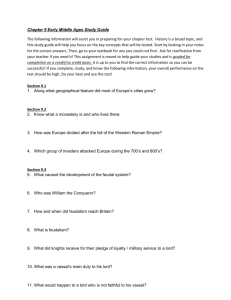

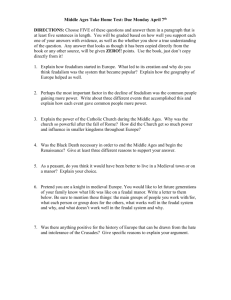

FEUDALISM We are all familiar with the term Feudalism. The following is a brief overview of feudalism. This was a political system in place in Europe, Japan and China for many centuries. It is useful to reflect on the way this political system works to maintain social order. In many respects it is similar to the chiefdom political organization of the Celts or Africa. It is led by great families with political loyalties and alliances. It is interesting to look at Marvin Harris' writings about the development of bigmen, chiefs and states in this respect. As well, ponder the similarity between a chiefdom and feudal state. What are some of the primary similarities and differences? Feudalism was a medieval contractual relationship among the upper classes, by which a lord granted land to his men in return for military service. Feudalism was further characterized by the localization of political and economic power in the hands of lords and their vassals and by the exercise of that power from the base of castles, each of which dominated the district in which it was situated. This formed a pyramidal form of hierarchy. The term feudalism thus involves a division of governmental power spreading over various castle-dominated districts downward through lesser nobles. Feudalism does not infer social and economic relationships between the peasants and their lords. This is better defined as manorialism. In theory, diagrammatic feudalism resembles a pyramid, with the lowest vassals at its base and the lines of authority flowing up to the peak of the structure, the king. In practice, however, this scheme varied from nation to nation. In Germanic Europe, the pyramid ended at the level below king or emperor, that of the great princes. In other words, the German kings were never able to impose themselves at the top of a system that had developed out of royal weakness. They were recognized as feudal suzerains but did not exercise sovereignty. In western Europe (France), the kings overcame the same handicap, using their positions to become feudal sovereigns. In England, where feudalism was imposed by the Normans, the kings were at the top of the pyramid, ruling by grace of their offices rather than by the grace of their feudal positions. The extent of feudalism must not be exaggerated, however. Many portions of Europe were never feudalized. Feudal institutions varied greatly from region to region, and few feudal contracts had all the features here described. Common to all, however, was the process by which one nobleman (the vassal) became the man of another (the lord) by swearing homage and fealty. This was originally done simply to establish a mutually protective relationship, but by A.D. 1000 vassalage brought with it a fief--land held in return for military service. With the vassal's holding of a fief went rights of governance and of jurisdiction over those who dwelt on it. Lord and vassal were interlocked in a web of mutual rights and obligations, to the advantage of both. Whereas the lord owed his vassal protection, the vassal owed his lord a specified number of days annually in offensive military service and in garrisoning his castle. The lord was expected to provide a court for his vassals, who, in turn, were to provide the lord with counsel before he undertook any initiative of importance to the feudal community as a whole--for example, arranging his own or his children's marriages or planning a crusade. In addition, the lord frequently convened his vassals "to do him honor." Financial benefits accrued largely to the lord. A vassal owed his lord a fee known as relief when he succeeded to his fief, was expected to contribute to the lord's ransom were he captured and to his crusading expenses, and had to share the financial burden when the lord's eldest son was knighted and his eldest daughter married. In addition, a vassal had to seek his lord's permission to marry off his daughter and for himself to take a wife. Should the vassal die leaving a widow or minor children, they were provided for by the lord, who saw to their education, support, and marriage. Should the vassal die without heirs, his fief escheated, or reverted to the lord. Feudalism had hardly begun before its first important sign of decline appeared. Problems with inheritance soon became a critical weakness. When a lord was no longer able to enter into an agreement with his vassal, freely accepted by both parties, then the personal nature of the feudal contract was seriously undermined. This transformation occurred before 1100, as did the beginning of the commutation of personal military service into money payments (called scutage in England), which further undermined the personal loyalty central to original feudalism. A late medieval outgrowth of this commutation was contract service in return for land or money, embodying loyalty to a lord in return for help and protection. This form of social bond enabled wealthy lords to field an army quickly when needed and gave them tangible and effective means to assert their own private influence in political and social life, to the detriment of orderly central government. Something else that appeared early in the history of feudalism was liege homage, by which a man who was the vassal of more than one lord chose one as his paramount lord, thus again subverting the original feudal idea of personal loyalty between lord and vassal. The centralization of strong lordships, whether as kings (as in England and France) or territorial rulers (as in the Holy Roman Empire), obviously undercut the localization of government so essential to feudalism. So too did new forms of warfare following A.D. 1300. Feudalism's decline was also rooted in ties to family and for other social changes. Family ties came to be seen as more important than territorial or protective concerns. The economic and social gulf between greater and lesser nobles grew wider, and respect for historically based ties of mutual relationships between lord and vassal steadily weakened. These circumstances, as well as the increasing division of inheritances, all combined to destroy feudalism, slowly and inexorably. The process was largely complete by the end of the 14th century. It should be noted that many of the problems associated with feudalism in Europe were not as noteworthy in Japan where the system seemed to have greater stability. However, in Japan the system did weaken for similar reasons as found in Europe.