Advantages and Disadvantages of the Act

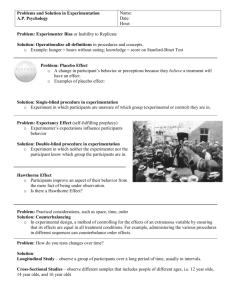

advertisement

Goodluck H. Methods for Assessing Children's Syntax The Act-Out Task Introduction: The Procedure and Its Uses The act-out task was first used to study children's knowledge of syntax by Chomsky (1969). Chomsky used act-out to study the acquisition of missing subject (PRO) and object constructions and definite pronoun interpretation. In the 1970s and 1980s act-out was used in numerous studies of syntactic development in children and, to a lesser extent, adult second language learners. In addition to being used in many studies on the topics first tackled by Chomsky, the technique has been applied to the study of relative clauses, passive sentences, and constraints on question formation, as well as to semantic phenomena, particularly the meaning of prepositions. Table 1 lists (nonexhaustively) studies in each of these areas. The act-out task is not a complicated procedure. The experimenter reads (or plays a recording of) a sentence to the subject, who then acts out his or her interpretation of the sentence, using a set of props provided. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Act-Out Task Six Advantages First, the act-out procedure has a good track record, having proved sensitive to quite fine-grained syntactic distinctions. The task is particularly well suited to testing of binding possibilities for empty and pronominal/anaphoric categories, since it provides a clear indication of the subject's interpretation of such categories. Second, the procedure is nonintrusive; that is, it allows subjects to volunteer their interpretations of sentences, without presetting a range of interpretations for them to choose from. This is an important advantage of the task, granted that child grammars may deviate to a greater or lesser extent from adult grammars, conceivably in ways currently beyond the imaginations of linguists. Table 1 Selected child language studies using the act-out technique Constructions tested Grammatical principles and/or interpretive strategies tested Missing subject (PRO) Minimal Distance Principle; c-command constructions restrictions on obligatory control Missing object constructions (easy and purpose clause constructions) Relative clauses Lexical selection of missing object complements; c-command restrictions on operator binding Sentences with pronouns and Effects attributable to Principles A, B, and C of the binding theory (Chomsky 1981) Parallel function hypothesis; conjoined clause analysis Studies Age of Subject s (years) Chomsky 1969 Maratsos 1974b Goodluck 1981 Hsu, Cairns, and Fiengo 1985 Goodluck and Behne 1992 Chomsky 1969 Cromer 1970 Cromer 1987 Goodluck and Behne 1992 Sheldon 1974 Solan and Roeper 1978 de Villiers et al. 1979 Tavakolian 1981b Goodluck and Tavakolian 1982 Hamburger and Crain 1982 5-10 4-5 4-6 3-8 4-6&10 5-10 5-7 7-9 7-9 4-6 3-5 4-5 3-6 3-5 4-5 3-5 Chomsky 1969 Solan 1983, 1986 5-10 5-7 anaphors Wh -questions Passives Meaning and syntax of prepositions That-trace effects N - V = actor - action strategy; effects of verb semantics on passive comprehension Semantic feature hypothesis; order-ofmention strategy; pragmatic clues to word meaning Lust 1986, 1987 Stevenson and Pickering 1987 Chien and Wexler 1990 various 5-6 2-6 Phinney 1981 Bever 1970 Maratsos 1974a Armidon and Carey 1972 E. Clark 1973 Johnson 1975 Grieve, Hoogenraad, and Murray 1977 Stevenson and Pollitt 1987 3-6 2-5 3-4 5-6 3-5 4-5 2-3 2-4 Third, because the act-out task requires the subject to perform actions that vary from sentence to sentence, it may be less prone to response bias than tasks in which there is a fixed and restricted set of responses (e.g., judgment tasks or picture verification tasks in which the subject classes a sentence as "good" or "bad" as a description of an action or picture). Fourth, act-out tasks are quite easy to administer. No extensive training is needed, either for the subject or for the experimenter. Usually, at age 3 and older children are able to act out sentences successfully after seeing only two or three demonstrations performed by the experimenter and acting out two or three practice sentences themselves. Most experiments on syntactic topics require only a rather simple scoring procedure (e.g., marking the reference of a pronoun or empty category and whether or not the basic action of the clause(s) has been performed correctly). Since most child subjects do well on basic actions from age 3 onward, most scoring can be done by the experimenter as the experiment goes along. The ease with which act-out experiments can be administered gives the task an edge in situations where high reliance on even simple equipment such as an audio tape recorder is undesirable. Video and/or audio recording is more or less the norm for experiments, though, and can provide a helpful backup to the experimenter's on-the-spot scoring and a means of checking for errors in the presentation of stimuli, where the stimuli are not prerecorded. Fifth, because of its simplicity, the act-out procedure has the important advantage of being inexpensive, compared with some other procedures. Thus, it is a task that makes doing an acquisition experiment feasible for virtually anybody. Sixth, act-out tasks are fun. It is true that young children may be turned off by having to act out a long sequence of similar, boring sentences (though it is not clear to me that a certain amount of tedium really impairs the effectiveness of the task). But given an engaging set of props, the task is one that both children and adults alike often enjoy. It is thus well suited (although underused) as a measure of second language learning by adults as well as first language learning by children. Six Disadvantages The act-out task has a number of actual and potential disadvantages. First, there are certain types of construction (e.g., questions) that do not easily lend themselves to the task, and certain types of predicates are difficult to act out, such as predicates expressing mental states or feelings (e.g., want, hope, be happy, feel sad). It is up to the researcher to decide how detailed an act-out is needed to answer the research question at hand. Even if a predicate is difficult to act out, an indication of who the actor is can nonetheless often be given (by moving a prop, for example), and the experimenter can also follow up the act-out with questions (e.g., "who was happy?"). Second, the nonintrusive property of the task carries with it a disadvantage, namely, that certain interpretations may be available to the subject, but the subject may choose not to act these out. The task thus has the potential to give only a partial view of the child's grammar. Third, although act-out tests are quite easy to administer and score, the results may not always be easy to interpret. In particular, the task runs the risk that the subject does not act out what the experimenter said, but instead acts out some mentally readjusted version of the sentence. For example, suppose the experimenter asks a child to act out a sentence like (1), (1) He fell down after Fred left. in which coreference between he and Fred is barred in the adult grammar, and the child makes Fred the subject of both clauses. Does that mean that the child does not know the relevant restrictions on pronoun interpretation, or does it mean that what he acted out was a readjusted version of the sentence, (2), (2) Fred fell down after he left. in which coreference is permitted? Thus, ironically, a child's "error" of interpretation may be prompted by a desire to avoid the ungrammatical interpretation that the experiment intended to test knowledge of. Such readjustments may not always be so devastatingly misleading. The child may struggle to readjust a sentence so as to avoid an ungrammatical reading and fail to come up with a complete act-out; or the child may Produce an act-out of what is transparently a readjusted form, for exam-Pie, adjusting (3) to (4) to achieve a sentence in which the pronoun and the subject of the subordinate clause are allowed to corefer. (3) He hugged Tom before Fred left. (4) Tom hugged him before Fred left. Since act-out errors may cluster systematically around certain sentence types it is important to examine the patterns of incorrect act-outs and not to be afraid to interpret children's apparent mistakes as evidence of grammatical knowledge. Fourth, although act-out tasks are easy to administer and easy for subjects to catch on to, it still can be said that act-out is a cognitively complex task. As Saddy (1992) puts it with respect to the version that he employed: [A]ct-out... requires that the subject hold the interpretation of the sentence he is presented with in working memory... [I]t is necessary to decode the sentence, decide on a picture that will match his understanding and also plan the actions that will result... in depicting the meaning of the sentence... Act-out tasks do indeed put quite a few demands on the subject; in planning any act-out experiment, it is a worth while exercise for the experimenter to try out the task, to get a feel for exactly how hard a thing subjects are being asked to do. Fifth, related to the one just mentioned, a further disadvantage of act-out tasks is that they are not well suited for studying syntax in children younger than 3. The cognitive complexity of the task and the requirement that the child actively participate make act-out studies difficult for very young children. Moreover, children under 3 have been shown to be biased toward performing actions with the props made available, even when the stimulus sentence does not necessarily call for an action (e.g., in response to a question such as "Do you want to ... ?"). Sixth, the act-out task is potentially prone to certain response biases particular to the task. One frequently discussed potential bias is the "bird-in-the-hand" strategy. When a child incorrectly makes the subject of the first clause (the dog) the subject of the relative in sentences such as (5), (5) The dog kissed the horse that patted the sheep. is this because she has a nonadult rule for relative clauses or is it because she just hangs onto the toy she has used as actor of the main clause when acting out the relative clause? Although the possibility that some such biases enter into the data cannot be ruled out, I think it is fairly clear by now that a bird-in-the-hand strategy cannot be the whole source of some characteristic errors, such as the misinterpretation of (5) just described. Very few children who give a bird-in-the-hand response to relative clauses like the one in (5) will persevere with such a response when faced with an obligatory control PRO sentence such as (6). (6) The dog told the pig [PRO to pat the sheep]. The fact that putative agrammatical strategies for act-out depend on the particular sentence types being tested argues that their use is filtered through the child's grammar and is confined to cases where the child's grammar permits them to be used, either because the child does not have any firm rule yet for the particular construction or because the response given fits with a nonadult rule. However, response bias is a real contributor to the second disadvantage noted above, namely, the danger that children's responses may not give a full picture of their grammars. For example, if a child is presented with a sequence of two sentences like (7a-b) and chooses the same (nonmentioned) toy as referent of the pronoun (him) and PRO, (7) a. For him to kiss the pig would please the dog. b. PRO to hug the tiger would upset the horse. is this because the child does not have the adult preference for construing the PRO subject of a sentential subject as referring to an entity mentioned in the main clause, or is it because there is a carryover effect from the previous actout? We will come back to this problem and how to deal with it. Summary For children 3 years of age and older, the act-out task has been shown to be an effective measure of many aspects of syntactic structure, particularly the interpretation of pronominal and empty categories in noninterrogative constructions. The absence of a preset range of responses may discourage response bias and allows the child to reveal interpretations that the experimenter had not anticipated. Act-out experiments are easy to administer and score, and they are inexpensive and generally fun. However, act-out is a relatively difficult task and as such is not well suited for very young children, who may be prone to act without fully processing or understanding the stimuli. Nor is the task well suited as a measure of certain aspects of syntactic and semantic structure, for example, questions and certain predicate types. The freedom of response the act-out task gives the subject opens the door for mental readjustment of the stimulus which may or may not be detectable from the response; it also allows the subject to stick with particular interpretations of the stimuli, that is, to demonstrate only a subset of the range of meanings his or her grammar permits for a particular construction. (...)