8. From ACE Pedagogy to Generic Skills

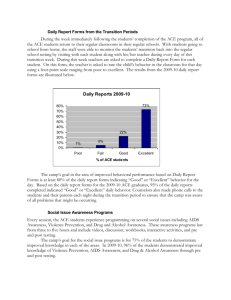

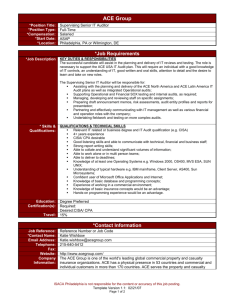

advertisement