Civilization II: Notes: French Revolution & Napoleon

advertisement

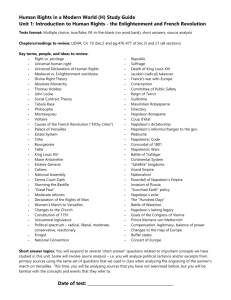

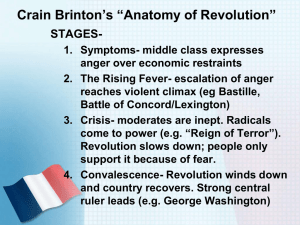

Modern World: Notes: French Revolution - Process of Building a Republic Summary – At the end of the eighteenth century, France was the largest and most populated country in Western Europe. While the country was greatly influenced by the Enlightenment, its absolutist monarchy and nobility resisted any political, social or economic changes. This resistance would spark the French Revolution, which would attempt to reform the country along the ideals of the Enlightenment – to make the country more free and equal. However, the revolutionary changes in France would unleash forces in French society that would upset the Enlightenment goals of the revolution, cause a reign of terror, wars across Europe and ultimately the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who would claim the title of French Emperor. Napoleon led France – and a large part of Europe - for over a decade, reorganizing the country and fighting wars. While Napoleon was ultimately defeated, his actions spread many of the ideas of the French Revolution to other countries. After Napoleon the countries of Europe worked together to prevent other revolutions and maintain European peace. However, the revolutionary ideas continued to cause turmoil in France and across Europe. During this postNapoleonic period, the French government swung back and forth between having an imperial monarchy and being a democratic republic. Only in the later part of the nineteenth century did France settle into an uneasy but stable republic. This unit continues to follow the focus on the theme of the conflict between political tradition and political change from the previous unit. The previous unit described the formation of the liberal value system. This unit will examine the differences along the spectrum of values and the conflicts between those values. It will also cover how philosophical differences based on these values change over time based on historical events. France Moves Towards Revolution “After us, the deluge” – Louis XV Under the form of absolute monarchy developed by Cardinal Richelieu and then refined by Louis XIV, France became the most powerful country in Europe. However, this power came at a price. The wars and royal palaces, such as Versailles, bankrupted the government and wasted national resources. The policies of Louis XIV and his successors placed greater tax burdens on the middle class and poor, while the nature of absolute monarchy resulted in the government disregarding the needs of this population. In addition, the kings who followed Louis XIV continued his policy of fighting wars and lavish spending on Versailles, but ignored the growing political and economic problems building up in France. In 1774, Louis XVI became the King of France. He was faced by many economic problems that weakened France. The cost of building Versailles, fighting foreign wars, and helping the American Revolution had left France with a large national debt. Worse, by 1787, banks across Europe refused to lend any more money to France. This forced Louis XVI to deal with the issue of taxes. The core of the tax problem was rooted in the class structure of French society, namely the nobility paid no taxes and the whole tax burden fell on the common people. This meant that any program to change the tax structure would affect the whole of society. French society was still divided by the ideas of feudal Europe into Three Estates: First Estate – Catholic Church Clergy – 100,000 people. Second Estate – Nobility – 400,000 people. Third Estate – Everyone else – 24 million people (95% of population). In France, the First and Second Estates (called the “ancient regime”), even though they controlled most of the wealth did not pay any taxes. In addition, due to the practice of “tax farming” created by Jean Baptiste Colbert, the Second Estate had profited from investing in companies that collected taxes from the Third Estate. It is estimated that 25% of the taxes paid by the Third Estate went to the profits of the tax farming companies. As a result, both the First and Second Estates had an economic incentive to prevent any major change. In addition, the Third Estate represented two very different populations: middle class and peasants. The middle class was influenced by writings of Enlightenment thinkers and wanted to use its growing economic power to gain more political power. The model was to gain the power enjoyed by the House of Commons in the British Parliament. In contrast, the peasants wanted more land and freedom from their feudal obligations. Louis XVI attempted to solve the problem by taxing the nobility (who paid no taxes), but the nobles thwarted this solution. As a result, by 1788, half of all tax money collected by the government went to paying the interest on the accumulated government debt. In order to address the financial problems, Louis XVI called a meeting of the Estates General in 1788. The Estates General, an institution dating back to the Middle Ages, was a gathering of representatives of each Estate. The purpose was to gain the support of the whole population for changing the tax code. While the nobles and Church appointed their representatives, the representatives of the Third Estate were elected by popular vote. Many representatives used this fact in combination with the ideals of the Enlightenment to claim that they represented the nation of France. In addition, because of the large number of people represented by the Third Estate, it had twice as many representatives are the First and Second Estates. On May 1, 1789, the Estates General met for the first time in 175 years to settle the problem of taxes. The previous year’s harvest had been one of the century’s worst. As the meeting began, the poor of France were at the verge of starvation and the edge of rebellion. From the very beginning of the meeting there was a conflict between the Third Estate and the rest of the meeting about voting. At previous meeting of the Estates General, each Estate had one vote. This meant that when voting on any issue, the First and Second Estates could out vote the Third Estate. Aware of this, at the meeting of the Estates General, the Third Estate demanded that each representative would get one vote. This meant that they would have more votes than the combined First and Second Estates. Louis XVI, the First, and Second Estates, opposed this plan since they would be vastly outvoted by the Third Estate. On June 17, 1789 the Third Estate left the Estates General in protest and formed itself into the National Assembly. It declared that it was the true representative body of the French people. In response, Louis XVI ordered that doors to the National Assembly’s meeting hall be locked. This action pushed France to the point of crisis. The members of the National Assembly defied the King on June 20, 1789 when they met on an indoor tennis court. They all swore the “Tennis Court Oath” to continue to meet until France had a national constitution. On June 27th, Louis XVI gave into the National Assembly and told the representatives of the First and Second Estates to join the National Assembly. The French Revolution Begins – The Bastille While Paris was focused on the political changes in the National Assembly, it was also suffering bread riots and general lawlessness due to the pervious year’s poor harvests. In the midst of this chaos, because he did not trust the French soldiers in Paris, Louis XVI ordered his Swiss Guard, mercenary soldiers, to move to Versailles, the royal palace fifteen miles outside of Paris. Many in Paris interpreted this to mean that Louis XVI was positioning his military force to shut down the National Assembly. Fearful of the possible attack of the Swiss Guard, the people of Paris, already rioting over the price of bread, attacked the Bastille, a fortress and prison, in the center of Paris to get weapons and gunpowder. The attack on the Bastille, on July 14, 1789, marked the start of the French Revolution. The Bastille symbolized the power of the king and the attack on the Bastille showed the violent course of the Revolution. Following a day-long siege of the Bastille, the citizens of Paris took the fortress. This victory only emboldened the French peasants to take further action. Louis XVI reacted by doing nothing. In fact, in his personal diary, Louis’ entry for the day was “Nothing”. Not knowing how the king would respond to the attack on the Bastille, a panic swept over the peasants and poor people of France. The chaos of the revolution drove over 20,000 French nobles to flee France. The poor and peasants believed that these nobles had left France for the purpose of recruiting armies to bring back to France to put down the revolution. The peasants responded by attacking churches and nobles across France, in an event called the Great Fear. In essence, large parts of France fell into anarchy. Many nobles fled France to other European countries, where they were known as “émigrés”. The émigrés worked to gain support of other European noble to fight against the revolution. At this point, the Revolutionaries could be divided into two groups, each with a different goal for the revolution. Both groups were named based on the style of their pants: Culottes – which means “knee-breeches” were the middle class supporters of a revolution based on Enlightenment ideals. They were called the Culottes because they wore the long stocking that were in fashion. Sans-Culottes – which means “without knee-breeches” were the peasants and urban poor who wanted food and revenge on nobles and the Catholic Church. Their name was because they wore the long pants of laborers. While the Culottes would try to move the revolution in the direction of forming some form of an elected constitutional government, the more radical members of the Sans-Cullottes would fight for a complete reformation of French society. Over time, the revolution would evolve to become a struggle between these two groups. On August 4, 1789, National Assembly, in an effort to end the Great Fear by incorporating the ideals of the revolution in law, officially ended the traditional privileges of the Church and nobility. Then on August 27, 1789, National Assembly passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This document, beginning with the statement “All men are born and remain free and equal in rights”, outlined the goals of the revolution. The Declaration went on to say that, “The source of sovereignty lies essentially with the Nation”, which meant the power to rule France was based on the people of France. Essentially, the document espouses Rousseau’s ideas from the Social Contract. Interestingly, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was signed one hundred years after the English Bill of Rights. “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” –Revolutionary Slogan The Declaration of the Rights of Man reflected the goals of the Culottes, but provided little real benefit to the poor of Paris. In October 1789, a mob of poor women, upset over the high price of bread, attacked Versailles, captured the king, and brought the king and his family to Paris where they lived in a Parisian palace as “prisoners” of the National Assembly. However, their condition worsened in June 1791, when they were captured attempting to escape France. From this point on they were treated more as prisoners of the National Assembly. French Revolution The culminating work of the National Assembly was the drafting of a new constitution for France. The new constitution approved by the National Assembly in 1791 reflected the ideas of the Enlightenment. In the constitution, the king became a limited monarch and all of the laws would be made by the elected Legislative Assembly. The right to vote was extended to all men. Further, France was organized into 83 Departments, each run by a local government. From the perspective of the Culottes this constitution achieved their goals for the revolution. After the adoption of the constitution, the National Assembly dissolved itself and new elections were held to form the Legislative Assembly. An important condition in the formation of the Legislative Assembly was that members of the National Assembly could not be part of the Legislative Assembly. As a result of this and because of the result of larger voting population, the Legislative Assembly was politically more radical, and gave more voice to the demands of the SanCulottes. However, the Louis XVI was not happy with his reduced power and refused to accept the new constitution. The attempted escape of the Louis XVI in 1791 weakened the power of his supporters and strengthened the power of his enemies in the newly elected Legislative Assembly. The Legislative Assembly was deeply divided over the future path of the revolution: Left – Jacobins – Radical democrats against the king. They wanted to abolish the monarch and make France a republic. Center – Girondins – Supporters of a constitutional limited monarchy. Right – Feuilliants – Supported the new constitution, but wanted to strengthen the monarchy. The names used to identify the groups came from the location where they sat in the meeting hall. The Jacobins sat on the left side on the meeting hall in a balcony and were referred to as the “Mountain”. The Girondins sat in the center of the hall and were called the “Plain”. The modern division of the political spectrum from left (liberal) to right (conservative) is based on the seating plan in the French Legislative Assembly. War and Terror At this point, the Girondins looked to spread the revolution beyond France’s borders to the rest of Europe. In 1792, as a way of spreading the revolution, France went to war against Austria. The war went badly for France. By the summer of 1792, both the Austrian and Prussian armies were marching on Paris. The commanding Austrian general warned of violent retaliation if any harm should befall the French royal family. In response to the Austrian and Prussian advance on Paris, the urban poor Sans-Cullottes began to exert more pressure on the events in Paris, which made the revolution more radical. Many Sans-Cullottes believed that the royal family was plotting with the invading European armies to defeat the revolution. On August 9, 1792, a mob of SansCullottes attacked the royal family, killing their bodyguards, and forcing the family to seek protection in a meeting of the Legislative Assembly. The next day, the Legislative Assembly moved to suspend the monarchy and make France a republic. Louis XVI ceased to be the King of France. He was now “Citizen Capet”, based on the name of the first King of France. The republican government declared that the term “Citizen” was to be used to address all people in France. In establishing a republic, the Legislative Assembly called for national elections. On September 22, the French army won the Battles of Valmy and was able to beat back the Austrian and Prussian armies. While this saved Paris, the war continued. One reason the war dragged on is the fact that the other monarchs of Europe were fearful that the ideas of the French Revolution would infect their own populations. They hoped that if they could militarily defeat the French they could end the revolution and restore Louis XVI and monarchy to France. On the same day as the Battle of Valmy, the new French Government, the National Convention met in Paris. A republican government, the National Convention worked to consolidate the revolution and win the war against the invading armies. In order to maintain and administer government power during this crisis, the National Convention formed committees that were charged with running different aspects of the government. As the crisis deepened, these committees, especially the Committee of Public Safety and the Committee of General Security emerged as centers of power. During this crisis, the Jacobins, radical democrats, led by Georges Danton, Jean Paul Marat, and Maximilien Robespierre (called the “incorruptible”), rose to power. The Jacobins feared that enemies both inside and outside of France were destroying the revolution. They moved to take power in the National Convention and rid France of any enemies of the revolution. Robespierre and Marat relied on the power of the Sans-Cullottes in Paris to support their ideas. In September 1792, a mob of Sans-Cullottes in Paris massacred a group of 1400 prisoners held in the city jails they believed were trying to overthrow the government. This event indicated the power of the mob in directing the actions of the revolution. The Jacobins would attempt to wield the power of the mob to recreate France based on their ideals. The Jacobins’ first target was Louis XVI, whom they felt was a traitor and that it was too dangerous for him to live. From the Jacobin perspective, as long as Louis lived there would be pressure to return him to power and undo the revolution. The fate of Louis XVI was more than judgment of his reign; it was a test of the future of the revolution. After a trial in which Louis XVI was found guilty by one vote, on January 21, 1793, he was publically executed by the guillotine in the center of Paris. In October 1793, Queen Marie Antoinette was executed. Most of the royal family perished during this period. While the Jacobins gathered strength, the moderate Girondins proved incapable of governing the country. In March 1793, a royalist revolt broke out in Western France, and the revolution found itself at war both within France and with every major power in Europe. The weakness and inability of the Girondins to defeat these conflicts was an important factor in the rise of Jacobins. In April 1793, as the war continued, the Jacobins moved to rid France of people they considered to be enemies of the revolution. The Committee of Public Safety, led by Robespierre, began the Reign of Terror, in which the government used its powers to violently terrorize and silence any opposition to the government and force the population to obey government rules. During the Reign of Terror, 40,000 French citizens were killed by the guillotine, often on the flimsiest evidence and in rushed trials. In addition to public mass executions in Paris, the government had mobile guillotines carry the terror to the countryside. While many nobles were killed in the Reign of Terror, surprisingly 80% of the Terror’s victims were members of the Third Estate and included leading Jacobins such as Danton. Robespierre justified the Reign of Terror by claiming to be building a “Terror is nothing but “Republic of Virtue”. This was to be a society of harmony based on the ideals of the prompt, severe, inflexible revolution. The creation of an idealistic society meant the transformation of the entire justice; it is therefore an society. This is what the Jacobins attempted to do to France. In October 1793, the emanation of virtue.” Convention proclaimed a new calendar in which the beginning of the revolution was - Robespierre the year one and the months were associated with the weather of each season. The government also established the metric system of measurement. Robespierre went as far as to attempt the creation of a new religion for the people of France based on Enlightenment ideals. This new religion was to replace Catholicism. In November 1793, Notre Dame cathedral in Paris was declared to be the Temple of Reason. However, Robespierre believed that “Reason” was too abstract for most people and in May of 1794 he established the Cult of the Supreme Being, based on the writings of Rousseau, with the goal of creating a civic morality to get the people to support the new republic. As the Reign of Terror continued, Robespierre began to execute fellow Jacobins, such as Danton, who opposed his goals. Robespierre justified the violence of the Terror as part of the cost of building the Republic of Virtue. In many ways, Robespierre was a prototype of many modern dictators because of his willingness to use violence to create an ideal human society. After a year of Robespierre’s rule, by the summer of 1794, the people of France had enough bloodshed and the threat of invasion from the other countries of Europe had been beaten back. The government and the people of France began to fear Robespierre and the Jacobins more than they feared foreign invasion, and they turned on the Jacobins. On July 28, 1794, the Reign of Terror ended with Robespierre’s execution by the guillotine. The period after the downfall of Robespierre and the Jacobins is called the Themidorean Reaction, after the name of the month in the new calendar. Political prisoners held in jail by the Jacobins were released. The Jacobin clubs were closed and brief reign of terror was carried out against leading Jacobins across France. A new French constitution was drafted and put into effect in September 1795. This placed France under the control of a five-man group called the Directory and a two-house legislature. The effect of the new constitution was to exclude the population of Sans-Cullottes from power and to ensure the rule by moderate elements of society. However, this government was corrupt and did little to end the political and economic chaos in France or conclude the wars France was fighting against other countries. Unable to gain popular support, the Directory was forced to depend on the military to maintain power and order. This created the opportunity for Napoleon Bonaparte, and ambitious young general to seize power. Napoleon Seized Power By 1792, France was at war with Austria, Prussia, Britain, Spain, and Portugal – collectively known as the First Coalition. These countries feared that the ideas of Revolutionary France would spread to their own countries. In April 1793, as the Reign of Terror began, the National Convention ordered a levee en masse to raise an army to fight the other countries of Europe. Essentially, this action mobilized all of French society support the war effort. The National Convention was appealing to the concept of “nationalism” to organize the country for war. A member of the Constituent Assembly declared that, “Each citizen should be a soldier, and each soldier a citizen”. Men were drafted into the army, which numbered between 600,000 and a million soldiers. The rest of society was ordered to produce equipment and materials for the army. Despite its size, the French Army had few officers, since the nobles had fled France. As a result, the French Army tended to fight as a mob against the mercenary armies of the First Coalition. The fact that the French armies were victorious was a sign of how armies motivated by patriotism were superior to those motivated by money. The lack of French Army officers created the opportunity for young officers to rise quickly to positions of command. Napoleon Bonaparte was one of these officers. Through demonstrating his skills as a military leader he rose in rank and by age 26, he commanded his own army. In addition, Napoleon was a supporter of the Jacobin controlled government. Napoleon was an artillery officer. In battle he was a genius in using cannon to help his soldiers attack and force his enemies to retreat. Napoleon was also a master at executing difficult military maneuvers such as dividing his army in the face of an enemy and living off the land. These risky maneuvers won him battles in Italy and North Africa, and his victories made him a hero in France. By 1799, the Directory that had ruled France since the Reign of Terror was corrupt and had little popular support. In fact, the Directory had depended on Napoleon several times to put down rebellions. Napoleon saw this weakness and used military force to launch a successful coup d’etat, or “stroke of state”, against the Directory. At age 30, Napoleon ruled France with dictatorial powers and the title “First Consul”. Then, on December 2, 1804, with the support of the French people, Napoleon – taking the crown from the hands of the pope – crowned himself Emperor of France. Fifteen years after the abolition of the Bourbon monarchy and eleven years after the execution of Louis XIV, France submitted itself to a new monarch. Napoleon set his sights beyond France and sought to establish Bonaparte dynasties across Europe. He placed his relatives on the thrones of the countries he conquered. Napoleon’s Accomplishments “Frenchmen, you will doubtless recognize in this conduct the zeal of a soldier of liberty, a citizen devoted to the Republic.” - Napoleon Once in power, Napoleon redesigned France along the ideals of the French Revolution (although he kept all political power for himself). In principle, he gave the French people equality in law, opportunity to improve their situation, and a sense of national identity (fraternity). However, the price was liberty. Napoleon insisted on directly controlling all parts of his empire and personally leading the French army in battle. As a result, Napoleon seldom rested. He would work twenty-hour days and often dictated his commands to several secretaries at once. The Napoleonic Code is perhaps the greatest legacy of his efforts to redesign France. Under Napoleon’s direction, a group of lawyers collected and reorganized the roughly 300 different French legal systems and codes into one body of five codes of law that covered all aspects of law and guaranteed all citizens legal equality. Under Napoleon’s rule, this law code was instituted across Europe and in the overseas French Empire – for example, Louisiana. Because of its organization and dissemination, many legal systems across Europe and the world follow a system based on the Napoleonic Code. In addition, Napoleon reformed the civil service or bureaucracy to give people confidence in the government. Corrupt officials were fired and everyone was taxed fairly. In order to educate people to work in his government, Napoleon established public schools, called lycees, where any child could be educated. Appointment to university and government positions was based on merit, not family connections. Napoleon was also able to stabilize the French economy after more than a decade of revolutionary chaos by establishing the Bank of France in 1800 to regulate the supply of money. The Bank of France and the currency it established, the franc, remained the core of the French economy until France adopted the Euro in 1999. In dealing with France’s overseas empire, Napoleon attempted to bring it under his domain. The island of Saint Dominque (Haiti) had been the prize of the Caribbean. Its main export, sugar, had enriched France. During the French Revolution, a salve revolt led by Toussaint L’Ouverture had caused the French to lose control of the island. Napoleon sought to take back this colony. However, despite an armed invasion, he was unable to regain control of the island of Saint Dominque. This and the British domination of the seas, lead Napoleon to sell the Louisiana Territories to the United States in 1803 for $15 million. Napoleon promptly used the money from the sale of the Louisiana Territories to finance his military efforts in Europe. In a series of brilliant military victories, Napoleon made himself and France the dominant power in Europe. In 1805, at the Battle of Austerlitz, in the face of a combined Austrian-Russian Army twice as large as his own, Napoleon divided his army and used the two halves to confuse and then defeat the combined Austrian-Russian Army. Following the battle, Napoleon commissioned the construction of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris (However, the construction of the Arc was incomplete by the time of his defeat in 1812 and was not finished until 1836). In 1806, he defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Jenna. In control of Germany, Napoleon ended the Holy Roman Empire and organized the collection of German kingdoms into the German Confederacy. In 1807, Napoleon defeated the Russians at the Battle of Tilsit and forced the Russian Czar, Alexander I, to accept an alliance with France. Napoleon Falls from Power Between 1800 and 1810, Napoleon built the largest European empire since the Roman Empire. All the major European powers, except England, were either controlled by Napoleon or forced into an alliance with Napoleon. For Napoleon, England would be a particularly stubborn enemy supporting rebellions against Napoleon in Europe. Furthermore, England was an island and was protected by the powerful British navy, which made it difficult for Napoleon to conquer. Napoleon did make plans to launch an invasion of England, but his plans were crushed at the Battle of Trafalger where the British destroyed the French Navy. From this point on, England would refuse to make peace with Napoleon and would seek to attack him at any opportunity. The British actively supported the Spanish in their rebellion against Napoleon. The Spanish opposed Napoleon because he had installed his brother as the King of Spain. Napoleon dispatched an army to crush the Spanish rebellion. Unable to defeat the French, the Spanish fought a brutal “guerrilla war” (Spanish for “little war”) that the French were not able to win. The Spanish painter Goya recorded the brutality of this guerrilla war in a series of prints called “The Disasters of War”. The British send a 14,000 man army to support the Spanish and harass the French. Using the British navy, whenever the French were on the verge of defeating the British army, the army would be evacuated and reinserted in another part of Spain. While the Spanish and British were unable to defeat French or drive them from Spain, the ongoing war forced Napoleon to reduce his power in other parts of Europe to shore up his forces in Spain. Ultimately, this “little war” cost Napoleon 300,000 soldiers. Napoleon referred to this war as the “Spanish ulcer”. Napoleon instituted the Continental System to hurt Britain. Under this system, no European country could trade with Britain. The goal was to economically weaken Britain by denying it European goods. Napoleon hoped that a weakened Britain would negotiate a peace treaty with France. However, instead of weakening Britain, it led to Napoleon’s downfall. The Continental System did little real harm to Britain. British trade with its large overseas empire, all protected by the mighty British navy, kept Britain well supplied. Instead, the British blockade of France and it allies hurt the economy of Europe. This in turn, caused people to turn against Napoleon. Most importantly, Russia, led by Czar Alexander I, refused to obey the Continental System and sold grain and other foods to Britain. Napoleon could not accept Russia’s breach of the Continental System. He viewed this as a breach of a treaty and in order to preserve his dominance in Europe, he amassed a massive army for the goal of bringing Russia back into line. In June 1812, Napoleon invaded Russia with his 400,000 man Grand Army. Napoleon planned this to be a lightning victory, similar to his earlier campaigns, in which the Russians would be defeated by one decisive battle. However, instead of engaging in a direct battle, the outnumbered Russians retreated deeper into Russia, destroying everything that Napoleon’s army could use for support. This scorched earth policy was even applied to the traditional Russian capital of Moscow. After Napoleon took the city, the Russians burned it. Even after this, the Russians refused to surrender. Unable to force the Russians to surrender and with the cold Russian winter approaching, in October Napoleon began his retreat from Moscow. This was the point at which the Russian army attacked and pursued Napoleons army as it retreated.. Between the combination of the Russian attacks and the severity of the winter, only 94,000 men of the Grand Army returned from Russia. Of this, only 20,000 men (3%) of the Grand Army were still in fighting condition. The loss of the Grand Army in Russia fatally weakened Napoleon’s power. The combined armies of Russia, Austria, and Prussia advanced across Europe to end Napoleon’s rule in France. However, they were timid in their advance, which gave Napoleon the opportunity to regroup his forces. Despite the catastrophic losses of the Russian campaign, Napoleon was still not defeated. After returning to France, Napoleon raised another army and marched into Central Europe to battle the combined armies of Russia, Prussia, and Austria. After a series of inconclusive battles, in April 1814, Napoleon’s armies were defeated at the Battle of Leipzig in which more than 100,000 men were killed in four days of fighting. In fifteen months of fighting Napoleon had lost 2 armies or a total of a million men! France was exhausted from war. This defeat left Napoleon with an army of less than 80,000 soldiers and forced him to retreat back into France. This time the allied armies advanced and captured Paris. Faced with final defeat, Napoleon surrendered and was exiled to the island of Elba, in the Mediterranean Sea. Even though Elba was comfortable, Napoleon chafed under the realization that he had lost his dominance over Europe. On March 1, 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to rule France for “The Hundred Days”. The French welcomed Napoleon as a hero and he was able to quickly rebuild his army. Alarmed by Napoleon’s sudden return, the other nations of Europe moved quickly to stop him. On June 1, 1815, the British and Prussian Armies defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. The day long battle was only decided when the Prussian army arrived to reinforce the British. The British General, the Duke of Wellington, noted this when he said it was “a near run thing”. After Waterloo, Napoleon was exiled to the remote island of St. Helena, in the South Atlantic, where he died six years later. The Concert of Europe The French Revolution and Napoleon’s conquest of most of Europe overturned the traditional governments and societies of Europe. After Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, the traditional leaders of Europe, monarchs, attempted to re-establish their positions of power, prevent revolutions in their own countries, and prevent France from ever again becoming the dominant power in Europe. In 1814, representatives of the traditional governments of Europe met in Vienna, Austria, for eight months at a meeting called the Congress of Vienna. Together, England, Prussia, Austria and Russia, the countries that defeated Napoleon, attempted to re-establish order in Europe. Despite the fact that the meeting was to limit French power and influence, France was invited to participate in the Congress of Vienna and was represented by Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, Napoleon’s Foreign Minister. Even though he was negotiating from a weak position, Talleyrand was able to protect the territorial integrity of France and keep France as a major power in Europe. One reason for Talleyrand’s success was influence of Austrian Foreign Minister Prince Klemens von Metternich, who ran this meeting from behind the scenes. Metternich, after witnessing the Reign of Terror and Napoleon as the results of the French Revolution, believed that democracy was dangerous and that it was his duty to prevent democracy from spreading in Europe. Through his control of the Congress of Vienna, Metternich planned to prevent democracy from spreading in Europe by three methods: Legitimacy – Putting traditional kings back in power across Europe. Leaders who had lost their power due to Napoleon were put back in power. The brother of Louis XVI was made the new king of France. The new king was called Louis XVIII because Louis XVI’s son had died in prison during the revolution after his father was executed. A part of this restoration of traditional monarchs was the restoration of the traditional borders of countries. Balance of Power – The countries around France were enlarged and strengthened to prevent France from becoming too strong and so by prevent any future Napoleons. As Metternich said, “When France sneezes, Europe catches cold”. Concert of Europe – The rulers of different Europe countries agreed to support each other to suppress and prevent democratic or nationalistic revolutions in Europe. Despite the efforts of Metternich and the Concert of Europe, the ideals of French Revolution could not be ignored. The ideals of the revolution spoke to millions of people across Europe and, due to Napoleon, these ideas had been spread to every corner of Europe. The two main ideas that would spark conflict in Europe up through the twentieth century were: “The first and greatest concern for the immense majority of every nation is the stability of laws – never their change” - Metternich Nationalism - France’s revolutionary leaders had united France with the idea of nationalism. The idea of nationalism held that countries should be organized around a common language, culture, and history. It was this unity that French people used to fight against the foreign invaders during the revolution. France was the first country to have a national anthem and a national flag not based the symbol of a royal family or religion. Following the French Revolution, Napoleon had used the idea of nationalism to strengthen the power of France and conquer the other nations of Europe. The idea of nationalism spread across Europe with Napoleon’s armies. After Napoleon, the idea of nationalism took hold among the different ethnic groups in Europe. Each wanted to establish their own nations build on their national identities. While the countries of Western Europe (England, France, and Spain) were mostly based around national identity and the idea nationalism brought few changes, in Eastern and Southern Europe the idea of nationalism had revolutionary results. The traditional countries of these regions were not based around the idea of national identity or even religious identity. Most of these countries were ruled by kings who controlled regions with many different languages and religious groups. Now, due to nationalism, these different subject peoples wanted their own countries based on their national identity. The result of which would tear these countries apart. Democracy and political equality – The authority and power of traditional leaders had been successfully challenged. Common people had taken power and ruled themselves. This idea held and in the decades after the Congress of Vienna, the citizens of the countries in Western Europe would push to expand their power and further restrict the powers of the noble classes. Rethinking of Political Philosophy Understanding the history of period after the French Revolution, it is helpful to view it through the opposing philosophies of the period. Prior to the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the Age of Enlightenment, with its belief in reason and order, had been the dominant philosophical force in Europe. However, these Enlightenment ideals had been tarnished by the reality of revolution, dictatorship, and wars. Simultaneously, the ideology of the French Revolution of “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” had spread to all parts of Europe and became a motivation for many different European groups seeking to build their own countries out of existing empires. Hence, the different philosophies became the ideals for different groups seeking power across Europe. Conservative Philosophy The conservative forces, represented by Metternich and the Concert of Europe, worked to keep conservative traditional governments in power across Europe. Philosophically, Edmund Burke, a British conservative best represented the conservative side – especially as the nineteenth century progressed. Burke supported the abstract idea of “natural rights”. However he did not feel that these rights had any purpose in the distribution of authority in either government or society. For Burke, liberty and rights are built on the events of history and are not part of humans’ natural state. For example, the legal rights enjoyed by people in England are the result of English history and that other peoples should not expect to have the same rights. Burke differed from both Hobbes and Locke in how he viewed humans. He criticized both Hobbes and Locke for being too focused the individual as a being separate from society, which he called atomism. Instead, Burke viewed the role of individual as part of a larger organism – society. And while he did see people as reasonable, he thought that human reason was limited in its ability and could not be fully trusted. This meant that no person or group could ever expect to successfully use reason to build or guide a society. Rather, over history, each society had deposited its accumulated wisdom into the “general bank and capital of nations and ages” or tradition. For this reason, it was tradition that had formed governments and given certain groups liberties, and if other groups wanted liberty, they needed to work within this tradition. Again, British rights and democracy had evolved over centuries. They had not been created by revolution. Burke explained that this was the reason the French Revolution had not achieved its ideals and instead collapsed into the Terror and dictatorship. Burke predicted this when he wrote that it would soon turn into a “mischievous and ignoble oligarchy” and a “despotic democracy.” Still, Burke was a flexible conservative. He believed that all social institutions should change, but slowly and in a manner that builds on old institutions. As a result, revolution should be never be a calculated political action, but only used as a weapon of last resort. These conservatives were willing to work with and allow the educated and wealthy nonnoble members of society, such as the owners of industry, to participate in government. In general, these conservatives dominated governments in Western Europe, such as France and England. However, in Central and Eastern Europe, conservatives were fall less flexible and opposed any change in political or social institutions. This group could be considered to be reactionaries since they wanted to hold society in its status quo based on tradition and nobility. Essentially, they wanted to turn the clock back to before the changes brought on by the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. Reactionary conservative forces dominated governments in Central and Eastern Europe, such as Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Austrian Foreign Minister Metternich was a reactionary. Liberal Philosophy In contrast to conservatives, liberals represented a political philosophy more in line with the ideals of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Liberals wanted to change society to make it more free and equal; yet they did not want the wholesale overturning of society. They saw the ideals of equality, rights and democracy as social goal, they also recognized that a creating a democracy for a society unprepared for that type of government could be disastrous. However, liberals believed that government should actively prepare a society for democracy by introducing liberal reforms and promoting education. The British philosopher John Stuart Mill represented the ideas of liberalism. In general Mill’s philosophy sought the greatest freedom for the greatest number of people. He believed that the purpose of government was to allow the citizen the greatest freedom while still protecting that citizen’s freedom. However, Mill recognized the danger of majority population using its democratic power to abuse a minority population, which he called “tyranny of the majority”. Because of this Mill advocated a democracy in which the educated minority held more power (though powers to draft laws and stronger votes), that would train the uneducated majority how democracy works. In addition, this government would protect certain basic freedoms protected as “rights”. He also believed the purpose of government was to improve society and the welfare of the individuals in society through the redistributing of resources from the rich to the poor. Mill also held to the cornerstone of liberal belief was that government should be based on written laws. Mill believed the greatest triumph for civilization was to replace the rule of force with the rule of law. For liberals, education and basic social programs and protection were important roles for government. However, liberals were willing to compromise their ideals in the face of reality – chiefly the experience of the French Revolution. Liberals recognized the dangers of complete democracy and everyone having the right to vote. Often, the liberals wanted the right to participate in government only extended to people who were educated and owned property. Over the nineteenth century, some liberals would advocate a stronger role for the government in redistributing wealth and running the economy and become known as social democrats. Beyond the liberals were the radicals who wanted to extend the rights of liberty and equality to everyone in society. The radicals held to the universality of rights and believed that the French Revolution was successful and should be emulated. To the radicals, both liberals and conservatives were enemies, the liberals because they compromised too much and conservatives because they tried to prevent the goal of universal rights and democracy. Radicals dominated many of the revolutionary groups that organized to overthrow the government of Europe. Over the course of the nineteenth century, these radicals would adopt the philosophies of communism and anarchism. Restoration France and the Revolts of 1830 As a result of the Concert of Europe, in 1814 France was again made a monarchy with a Bourbon king, Louis XVIII. Louis XVIII did retain a parliament, but it was made up of nobles. Most Frenchmen were denied the right to vote. In addition many of the popular people linked with Napoleon’s government were harassed, arrested and even killed by the government. Despite the efforts of the Concert of Europe, France remained the center of revolutionary thought in Europe. Former supporters of Napoleon, known as Bonapartists, retained their organization and unity “underground”. In addition, radicals from across Europe went to France to organize secret groups, learn new ideas, and plan for future revolutions in their own countries. The opportunity for a rebellion began in 1824 following the death of Louis XVIII. The new King of France, Charles X , tried to make himself an absolute monarch and return France to its pre- revolutionary traditions. He also paid nobles a total of one billion francs for estates and property lost in the French Revolution. As a result of these actions, in July 1830, the workers and liberals rallied under the tri-color flag of the revolution and violently revolted against Charles X in the “July Revolution”. When Charles sent soldiers to suppress the rebellion and kill the rebels, the soldiers refused to follow orders and joined the rebellion. In the face of this popular uprising, King Charles X fled France for refuge in England. However, rather than create a democratic-republic, the middle class liberals chose a new king, Louis Philippe, and limited his power. Louis Philippe was a member of the Bourbon family, but had fought on the side of the Revolution in 1789. The liberals did this because they feared that the Concert of Europe would attack a new democracy if it went too far and that a pure democracy would give too much power to the poor. The 1830 Revolution was successful in that it ended the threat of counter-revolution from traditional forces within France and ended the power of legitimacy imposed by the Concert of Europe. Louis Philippe took the title “King of the French” and was often known as the “Citizen King”. He allowed an extension of voting rights to those with substantial property – roughly 250,000 out of a population of 35 million. The idea was that property owners would support a conservative government that could keep peace and order. Louis Philippe’s chief minister advised people who wanted to participate in government to “work hard, grow rich, and so gain the vote”. Revolts of 1848, the Second Republic & the Second Empire In France, Louis Philippe had become very unpopular – voting rights had not been extended far enough and workers were politically powerless. Several years of poor harvests had only increased the misery of the poor and working classes. However, those opposed to the government were divided between radicals, seeking a republican government and universal voting rights, and liberals, who wanted a limited extension of voting rights. This division made it difficult to launch an opposition to the government. In addition, it meant that many who opposed the government (particularly radicals who were anti-capitalist and anti-bourgeois) saw the struggle in terms of social and economic issues, not just political issues. These radicals were not only interested in winning democracy, they also wanted to change the economic structure of society so more wealth went to the poor. In February 1848, the poor French workers again rose up in rebellion against the king, Louis Philippe. In the face of rebellion, Louis Philippe fled France of England. The Second Republic was declared. A vote, by universal male suffrage, elected the Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution for France. The Constituent Assembly represented people from across France, both liberals and conservatives. The revolutionaries in Paris were radicals, and they feared the Constituent Assembly would take away the gains for which they had fought. On May 15, 100,000 Parisian working class radicals attacked the Constituent Assembly and declared their own government. The Constituent Assembly turned to the army to crush the radical workers’ rebellion. Unlike 1830, this time the army did suppress the rebellion. Between June 24th and 26th, bloody class warfare, between the middle class and the poor, raged in Paris. In the end, the Constituent Assembly won. The captured radicals were either executed or sent to penal colonies outside of France. After the revolt was put down, in December 1848, the people of France elected Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, to be the new president of France. This is surprising since, prior to 1848, Louis Napoleon had been living in exile in England and was not the leader of any political group with in France – this turned out to be an advantage. Louis Napoleon became president by taking advantage of the political divisions in France between royalists, Bonapartists, liberals, and radicals to cement his hold on power. Louis Napoleon was everyone’s second choice. This meant that each group, if they could not have their leader become president of France, would rather have Louis Napoleon as president than the leader from another group. Louis Napoleon had been a liberal in his youth and as President, he had large plans to redesign France. However, the conservative forces in the Constituent Assembly blocked any reforms that he tried to make. In frustration, he turned against the Constituent Assembly and began to rally the people of France to his reforms. Then, in December 1851, Louis Napoleon with support from the army, carried out a coup d’etat and over threw the Second Republic. Later in the month, though a popular election, Louis Napoleon got the support for a new constitution that made him president for 10 years. The constitution also allowed for universal male suffrage, but that did not matter since Napoleon held all the real power. Later, in November 1852, he made himself Emperor of France with the popular support of the French people. He took the title Napoleon III, ruler of the Second French Empire. As Emperor, Napoleon III focused his energies on building up the French economy and expanding France’s overseas empire. One of his long lasting actions was to demolish and rebuilt central Paris to be a city of wide boulevards and parks with grand government buildings. While this made the city more beautiful, Napoleon’s real reason was to make a city where his soldiers could quickly end any future street protests and rebellions. In the process of doing this, Napoleon III destroyed the working class slums in the center of Paris, however the project also created work opportunities for many of the slum dwellers. In addition, he ordered building of the railroad network across France. During the 1850’s the rail system in France increased from 3,000 to 16,000 kilometers. This project helped develop the modern capitalist economy in France because it funded the mining of coal and steel, building steel mills and a financial system to fund the program. In addition, gave work to people and created more commerce, which won Napoleon III the support of workers and industrialists. He celebrated France’s growing industrial power by holding the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1855 (Britain had held the first of these “The Great Works of Industry” in 1850). In addition, Napoleon moved France closer to Britain, by agreeing to a Free-trade treaty, as he expanded France’s overseas empire. This common support of the principles of free trade led France and Britain to work together to take over parts of China. He also had French forces take over Indochina (now Vietnam and Cambodia), parts of Africa (including the building of the Suez Canal by a French company, and attempt to take over Mexico (which ended in disaster). Unlike his uncle, Napoleon III started out as an authoritarian leader, but over time became more liberal. The second half of his reign (from 1860-1870) has been called the “Liberal Empire”. In order to keep the support of both the business interests in France and the French population, Napoleon began a series of reforms that began with giving the Parliament the power to debate and vote on his government budgets. Three years later he allowed for freedom of the press and gave the population the right to assemble and form political associations. At the same time, workers were given the power to form unions and strike for better conditions. Finally, in 1869, he allowed some leaders in Parliament to form a government, which lead to the development of a constitutional limited monarchy. End of the Second Empire & the Third Republic Over the course of the nineteenth century, the small central European country of Prussia began to consolidate its political, economic and military power into building the country that would become Germany (the class will study this in the next unit). The leader of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck fought a series of wars as part of this process of building a united Germany. Prussia’s war against Second Empire France was the final part of this process because only France stood as an obstacle to Prussia unifying Germany under its control. French Emperor, Napoleon III found himself in conflict with Bismarck over a number of issues in Europe, which generally went in favor of Bismarck. In an effort to demonstrate French dominance, Napoleon III allowed himself to be led into a diplomatic trap by Bismarck. On July 19, 1870, bowing to popular demands, Napoleon III declared war on Prussia – he expected that the larger French army would crush the Prussians. However, the faster moving and better equipped Prussian army surrounded the French army and Napoleon III at the Battle of Sedan. Following the battle on September 1, 1870, Napoleon III became a prisoner of Bismarck and the Second French Empire ended. The surrender of Napoleon III did not bring an end to the Franco-Prussian War. France formed a new government called the Government of National Defense to negotiate a peace treaty with Prussia. As a condition for peace, Bismarck demanded that France surrender the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to Prussia. The French refused to meet this demand and quickly raised a new army. As the French regrouped their army, the Prussian army laid siege to Paris. For four months, the Prussian army attacked Paris while the Parisians slowly ran out of food. While the siege of Paris continued, Bismarck further insulted the French by having the Prussian king Wilhelm I proclaimed Emperor of Germany, or Kaiser, at the French palace of Versailles, on January 18, 1871. For the Germans, this event began the Second German Empire, called the Second Reich (the First Reich was Charlemagne’s Frankish kingdom of the Middle Ages). Facing mass starvation and after butchering all the animals Paris, the Government of National Defense surrendered to the Prussians on January 28, 1871. In the Treaty of Frankfurt, Bismarck was determined to eliminate France as a possible threat to Prussian power in Europe. The treaty forced the French to surrender the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to Prussia and pay the Prussians 5 billion francs in reparations for the war. The combination of lost territory and war reparations would remain a point of bitterness for the French until the end of World War One, when France would have its revenge. After the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second Empire, France returned to being a republic. This republic was built on the government that had developed under Napoleon III in the liberal period of his rule. However, after the war, France was a bitterly divided society that was caught in never ending political conflict between the liberals, who supported the Republican ideals that stretched back to the French Revolution, and the conservatives, who still wanted some form of monarchy. Adolphe Thiers, a French leader in the Republican government said that this was "the form of government that divides France least".