National Audit of Scotland`s Outdoor Sports Facilities

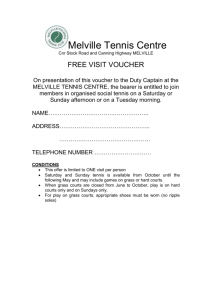

advertisement