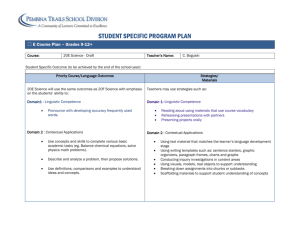

2.1. Plurilingual and pluricultural competence

advertisement