Rosenhan Worksheet 2011(NM)

Rosenhan (1973)

On Being Sane in Insane Places

Field of psychology: Individual Differences

1. CONTEXT AND AIMS

Context

How do we define sane? How about insane? Is there a difference? How do we tell?

Historically, psychiatry has been accused of classifying dissident mental traits as abnormal and a disease before.

For example, in 1851, American physician Samuel A.

Cartwright (above) described a mental illness he called

Drapetomania, where a slave wishes freedom from his master. Cartwright was quoted as saying of slaves "If any one or more of them, at any time, are inclined to raise their heads to a level with their master or overseer, humanity and their own good requires that they should be punished until they fall into that submissive state which was intended for them to occupy. They have only to be kept in that state, and treated like children to prevent and cure them from running away."

In PY1 we looked at some biological therapies. These therapies are based on the assumption that mental illness, like physical illness has its basis in biology. This concept is called the

medical model of abnormality because it aims to treat psychological disorders as if they were physical illnesses.

A key feature of the medical model is that mental illnesses are diagnosed in much the same way as physical illnesses. The doctor (psychiatrist) identifies a set of symptoms in the patient and uses these to identify a disorder.

In the 1960s psychiatrists such as Foucault, Laing and

Szasz launched the anti-psychiatry movement. They challenged the fundamental claims and practices of mainstream psychiatry, in particular the medical model of mental illness.

The anti-psychiatry movement questioned the validity of psychiatric diagnosis. What does this mean? (pg122)

Foucault (1961) cited the development of the concept of mental illness in the 17 th and 18 th centuries when unreasonable members of the population were locked away, institutionalised and subject to inhumane treatment (see drapetomania above). He argued that the label of “mental illness” was misused to keep control of people who were seen as a threat to society. Mental illness therefore is a social construct, with no legitimate basis in biology. They did not reflect quantifiable patterns of human behaviour, and which, rather, were indicative only of the power of the "sane" over the "insane".

What did Laing (1960) argue about schizophrenia?

Szasz (1960) argued that the medical model is no more sophisticated than believing in demonology

(believing that mental illness is caused by demons) and that it is unhelpful to our understanding of psychiatric conditions. He suggested that the concept of mental illness was simply a way of keeping non-conformists from society.

1

David Rosenhan was influenced by the anti-psychiatric movement, and he too questioned the validity of the methods with which psychiatrists diagnosed mental disorders. He did not argue that mental illness did not exist, nor that people could suffer great anguish because of it.

The belief has been strong that patients present symptoms, that those symptoms can be categorized, and, implicitly, that the sane are distinguishable from the insane. More recently, however, this belief has been questioned. ... The view has grown that psychological categorization of mental illness is useless at best and downright harmful, misleading, and pejorative at worst. Psychiatric diagnoses, in this view, are in the minds of the observers and are not valid summaries of characteristics displayed by the observed.

David Rosenhan

In other words, depending upon the situation and environment a person is in, they may be judged to be sane or insane. His main question was “If sanity and insanity exist, how will we know them?” We may think that we can tell the normal from the abnormal, but the evidence for this is less than compelling.

It is common to read about murder trials where the prosecution and the defence each call their own psychiatrists who disagree on the defendant’s sanity.

What does this suggest about the validity and reliability of diagnosis?

There is much disagreement over the meanings of such terms as “sanity”, “insanity”, “mental illness” and “schizophrenia”. If experts cannot even agree on the definitions of such terms, how can they possibly use the concepts to determine the sane from the insane?

Concepts of normal and abnormal are not universal. What is considered normal in one culture may be seen as bizarre in another.

Aims

Rosenhan wanted to investigate whether psychiatrists could distinguish between people who were genuinely mentally ill, and those who are not. He argued that the question of personality vs situation can be investigated by having ‘normal’ people (that is people who have never had serious psychiatric symptoms) seek to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. The aim was to investigate whether it was the characteristics of the individual which lead to a diagnosis of mental illness, or whether the context (the psychiatric hospital- the “insane place”) would have a greater influence. There were two possible outcomes:

1.

The pseudopatients would be identified as sane, and be discharged. If this were the case, we can assume:

2.

The pseudopatients would not be identified as sane, and/or labelled as insane. This would mean:

2

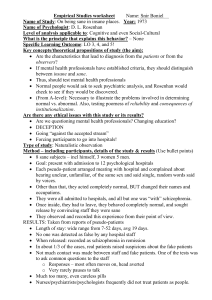

2. PROCEDURES (pg123)

Who were the participants?

Naturalistic observation (not a field study, as there is no real IV and DV) Research method used?

Study 1

Gaining admission

Each of the pseudopatients called a hospital and asked for an appointment. On arrival, he/she told the staff at the hospital that they had been hearing voices saying words that included “empty” “hollow” and “thud”. These particular symptoms were chosen because of their similarity to existentialist symptoms (the meaningless of life)

and their absence in the psychiatric literature of the time.

Aside from the description of auditory hallucinations, each pseudopatient described their life events accurately (both good and bad) and invented no more symptoms.

None of the pseudopatients had a history of psychiatric disturbance.

The hospitals varied from old to new, some were research based and one was a private hospital.

Life in the Hospital

Once in the hospital, the pseudopatients were instructed to behave normally, and other from some understandable nervousness and tension about being found out, they

behaved as they would outside of the hospital.

They spent their time talking to other patients and making notes of observations of life on the ward. Initially, notes were made in secret, but it soon became apparent that the staff

did not really care.

The pseudopatients secretly did not take their medication, but otherwise followed the rules of the ward, and behaved courteously and co-operatively.

Study 2

After the results of study 1 were published, staff in another hospital challenged Rosenhan claiming that this could not happen in their hospital. Rosenhan informed the hospital that in

the next three months, one or more pseudopatients would present themselves.

The staff were asked to rate one a 10 point scale their confidence that the person was genuinely ill (1 was high confidence, 10 was low). Judgements were obtained on 193 patients

admitted for psychiatric treatment during this time.

In fact, Rosenhan did not send any pseudopatients to the hospital.

Study 3:

During study 1, Rosenhan conducted a mini experiment to see how the staff responded to pseudopatients. In four of the hospitals, the pseudopatients approached a member of staff with the following questions “Pardon me Mr X, could you tell me when I will be eligible for grounds privileges?” or “When am I likely to be discharged?” The pseudopatients asked as normally as possible, and tried not to ask the same staff member more than once in a day.

As a control condition, a young woman approached staff members on the Stanford university campus, and asked them similar questions.

3

3. FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS (pg124-5)

Findings

Study 1:

All of the pseudopatients were admitted to the hospital, and all but one of them was diagnosed as

___________________________ (the other was diagnosed as ______________________________)

The range of stay was ___________________________________________.

Eventually there were all discharged from the hospital, but with a label of schizophrenia in remission

While the pseudopatients were at the hospital, their diagnosis was not questioned by the staff. The genuine patients at the hospital however regularly voiced their suspicions. They said that of the pseudopatients

“You’re not crazy”, “You’re a journalist” or “You’re a professor checking up on the hospital”.

The normal behaviour of the pseudopatients was interpreted as signs of their illness. o All of the pseudopatients made notes as part of the observation. This was interpreted as an aspect of their madness. Nurses record state “Patient engages in excessive writing behaviour.” o The label of mental illness shaped the interpretation of personal circumstances. A good example of this is below.

Rosenhan’s description of a pseudopatient

Psychiatrist’s description of the pseudopatient

“One pseudopatient had a close relationship with his mother but was

“This white, 39 year old male…manifests a long history of considerable ambivalence in close rather remote from his father during his early childhood. During adolescence and beyond however, his father became a close friend while his relationship with relationships, which begins in early childhood. A warm relationship with his mother cools during adolescence. A distant relationship with his father is described as becoming very intense. Affective his mother cooled. His present relationship with his wife was characteristically warm and close. Apart

(emotional) stability is absent. His attempts to control emotionality with his wife and children are punctuated with angry outbursts, and, in the case from occasional angry exchanges, of the children, spankings. And while he says that friction was minimal. The children had he has several good friends, one senses rarely been spanked.” considerable ambivalence in those relationships…

There was very limited contact time between the staff and patients. In one corner of the ward was a glass

“cage” where the staff had their offices. The amount of time that the attendants spent out of the cage was

11.3%, and much of this time was spent doing chores that mingling with the patients. o On average, the nurses emerged from the cage 11.5 times per shift o The psychiatrists were rarely seen on the wards, appearing about 6.7 times per day. o The average daily contact between patients and the psychiatrist was 6.8 minutes.

The pseudopatients recorded the conditions in the hospital. The staff treated them with little respect, beating them as punishment. There was little or no privacy for patients, as there were no toilet doors, anyone could read patient’s files and physical examinations were conducted in semi-public rooms.

Study 2:

Over 3 months, 193 patients were admitted to the hospital. Remember that Rosenhan sent no actual pseudopatients to the hospital

41 patients were judged to be pseudopatients by at least one staff member

23 were suspected by at least one psychiatrist

19 were suspected by one psychiatrist and one staff member

Study 3:

The most common response was a brief reply as the member of staff continued walking past without pausing or making eye contact. Only 4% of the psychiatrists and 0.5% of the nurses stopped. 2% in each group paused and chatted.

In the control condition, all the staff members on the university campus stopped and answered the questions, maintaining eye contact.

4

Conclusions

The general conclusion?

A woman making notes in a cafe. A sign of madness? What about if she was in a psychiatric ward? Is it the individual or the situation which leads

The psychiatrists failed to detect the sanity of the pseudopatients despite the to a diagnosis of mental illness? fact that they were clearly sane. Rosenhan concluded that “It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals. The hospital itself imposes a special environment in which the meaning of behavior can easily be misunderstood. The consequences to patients hospitalized in such an environment – the powerlessness, depersonalization, segregation, mortification, and self-

labeling – seem undoubtedly counter-therapeutic”.

Rosenhan claims that the misdiagnosis was due to the fact that doctors have a strong bias towards Type 2

errors - they are more inclined to call a healthy person sick (a false positive) than to call a sick person healthy

(a false negative, or Type 1 error). With physical illness, it is much better to be cautious and over diagnose rather than under diagnose. o Rosenhan maintained however that treating psychiatric illnesses the same as physical illnesses (as in the medical model) is not appropriate. “A type 2 error in psychiatric diagnosis does not have the same consequences it does in medical diagnosis. A diagnosis of cancer that has been found to be in error is cause for celebration. But psychiatric diagnoses are rarely found to be in error. The label sticks, a mark of

inadequacy forever.” o Having once been labelled schizophrenic, there is nothing the pseudopatients could do to overcome the label. Once a person is designated abnormal all of his other behaviours are coloured by this label. Indeed the label is so powerful that many of the normal behaviours were overlooked completely, or profoundly misinterpreted. This is demonstrated by the fact that when the patients were released from the hospital, they were still labelled as “schizophrenics in remission”.

What can we conclude from the behaviour of the staff towards the patients?

What do these results imply for mental health care?

5

4. EVALUATING THE METHODOLOGY (pg 126)

Method:

1.

What was type of observation was used? What advantages/disadvantages does this have?

2.

Study 3 was a field experiment. What advantages/disadvantages does this have?

3.

In study 3, they compared the results with a control condition which took place on a university campus.

Does this raise any methodological issues?

Reliability:

4.

The results of study 1 were based on the experiences of eight pseudopatients in a number of different hospitals. What does this imply about reliability?

5.

Could inter-observer reliability be assessed?

6.

Study 2 only involved one hospital. What does this imply for reliability?

7.

Could this study be replicated?

Validity:

8.

How often would a psychiatrist expect to come across someone who is pretending to be mentally ill?

What could this imply about the validity of the study?

9.

The hospitals selected for the study were in five different states on the west and east coast of America.

They varied in quality. What does this imply about validity?

10.

Did the study have ecological validity?

11.

At the time, the manual used for diagnosing was the DSM II. Today, doctors use the DSM IV. Would the results from Rosenhan’s original study still apply today?

12.

How valid is the claim that the behaviour of the pseudopatients inside the hospital was “normal”?

13.

The participants in study 1 did not know that they were in a study. What does this mean for validity? In study 2 they did know. What does this imply?

Sampling:

14.

The participants in this study were all the staff (including the doctors and nurses) in these particular psychiatric institutions. In which way might this sample not be representative? How does this affect the conclusions drawn?

Ethical issues:

15.

What ethical issues are raised in this study? For the staff, the pseudopatients, and for the real patents?

16.

What particular ethical issues could be raised by study 2?

17.

The general conclusion from this study could be seen to promote the idea that psychiatry is useless at best and dangerous at worst. What real world ethical issue could this raise?

5. CRITICALLY ASSESS WITH REFERENCE TO ALTERNATIVE EVIDENCE

One issue with Rosenhan’s research is that it has been argued that such a result would not be found if the study was repeated today, as the diagnosis of psychiatric conditions has become more stringent.

Slater (2004) did a partial replication of Rosenhan, although not as a piece of systematic research. She presented herself at 9 psychiatric emergency rooms with the lone complaint of an isolated auditory hallucination (the word “thud”). In almost all cases, she was given a diagnosis of psychotic depression and was prescribed either anti-psychotics or antidepressants. Slater concluded that psychiatric diagnosis was arbitrary.

However, there are two issues with this piece of research. Slater herself had previously been diagnosed with clinical depression. Also, a similar weakness of Rosenhan can apply here:

6

Therefore, the issues with Slater’s research may mean that we cannot really make any concrete conclusions about the validity of modern methods of diagnosing mental illness.

Another piece of alternative evidence that addresses this issue (that the results would not be applicable today) is that the criteria required for a diagnosis of schizophrenia has changed.

Read the modern diagnosis for schizophrenia

(right). Would Rosenhan’s pseudopatients be admitted to a modern psychiatric hospital? Why?

Criteria for Schizophrenia (taken from the DSM IV TR 2000)

Characteristic symptoms : Two (or more) of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period

1. delusions

2. hallucinations

3. disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence)

4. grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

5. negative symptoms, i.e., affective flattening, alogia, or avolition

Social/occupational dysfunction : For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, one or more major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset.

Duration : Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms.

Sabin and Mancuso (1980) noted that a psychiatrist using the modern (at the time) DSM III would not diagnose Rosenhan’s pseudopatients with schizophrenia for the reasons stated above. Carson (1991) likewise claimed that psychiatrists now had a much more reliable classification system, so this should lead to much more agreement in diagnosis.

One the one hand we could argue that this means that Rosenhan’s research is no longer valid.

However, we could also argue what?

However, even though it could be argued that diagnosis is much more reliable, there is still little evidence that the DSM is routinely used with high reliability by psychiatrists and psychologists. Similarly to how we assess the reliability of observations, the reliability of a diagnostic system (such as the DSM) can be assessed using inter-rater reliability. Diagnoses for the same patient are compared between psychiatrists. If the DSM is really as reliable as claimed, we would expect to see a high correlation. Whaley (2001) however found that inter-rater reliability can be as low as +.11 for some conditions.

So it would seem that there is still some unreliability in diagnosis. Rosenhan attributed this unreliability and bias to the situation in which the patients found themselves (the psychiatric hospital) which caused their behaviour to be misinterpreted as signs of mental illness. But what else can cause this unreliability? It is possible that the diagnosis could be biased by the beliefs and attitudes of the psychiatrist.

7

Loring and Powell (1988) gave a transcript of a patient interview and asked the psychiatrist to draw conclusions about the patient. Half of them were told the patient was white, half were told he was black. They found that psychiatrists appear to describe the black patients as being more violent, and view them with suspicion and danger.

How does this develop Rosenhan’s research?

Spitzer (1975) challenged Rosenhan’s findings. Spitzer argued that even though the pseudopatients were misdiagnosed, it does not invalidate diagnostic methods because

Psychiatrists have to rely upon the verbal reports of the patients who come to them for help.

It is not expected that an individual would try to trick their way into a psychiatric institution.

Spitzer argues that Rosenhan’s methods are meaningless for assessing the validity of diagnosis. He argues that if you fake a physical (rather than psychological) illness, such as complaining of severe stomach pain, you might be admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of gastritis. Even though the Doctor has been tricked, the diagnostic methods were not invalid.

Spitzer (1976) investigated the case histories of individuals with schizophrenia admitted to his own hospital and 12 other US hospitals. He found that the discharge diagnosis of

“schizophrenia in remission” is given very rarely.

What does this suggest about Rosenhan’s research?

Use three colours to highlight research that supports, contradicts, or develops Rosenhan’s research.

8