DOC Rosenhan summary

advertisement

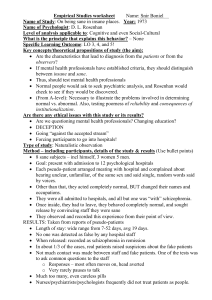

Core studies summary Rosenhan (1973) individual differences Aims and context (Put aims of study & background history): Aim – Rosenhan aimed to investigate if psychiatrists could distinguish the difference between people who are genuinely mentally ill and those who aren’t. He aimed to find out if “the salient characteristics that lead to diagnoses reside in the patients themselves or in the environments and contexts in which the observers find them?” He wanted to find out if the diagnostic systems were reliable at the time, as well as the impact of labelling. Coming to the fore in the 1960s, "anti-psychiatry" (a term first used by David Cooper in 1967) defined a movement that vocally challenged the fundamental claims and practices of mainstream psychiatry. Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz argues that "mental illness" is a combination of a medical and a psychological concept, but popular because it legitimizes the use of psychiatric force to control and limit deviance from societal norms (norms of society i.e. ways we are expected to behave) Michel Foucault argued that the concepts of sanity and insanity were social ideas (constructs) that did not reflect actual patterns of human behavior, and which were convenient for the powerful in society to judge who is "sane" over the "insane". The novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest became a bestseller, highlighting public concern about involuntary medication, lobotomy and electroshock procedures used to control patients. In the 1930s several controversial medical practices were introduced including inducing seizures (by electroshock, insulin or other drugs) or cutting parts of the brain apart (leucotomy or lobotomy), but there were grave concerns and much opposition on grounds of morality, harmful effects or misuse. In the 1950s new psychiatric drugs, notably the antipsychotic chlorpromazine, were designed in laboratories and slowly came into preferred use. In addition, Holocaust documenters argued that the medicalization of social problems (giving medicine to people who really had social problems) and euthanasia of people in German mental institutions in the 1930s provided the institutional, procedural, and doctrinal (beliefs of government) origins of the mass murder of the 1940s. The Nuremberg Trials convicted a number of psychiatrists who held key positions in Nazi regimes. 87 Rosenhan states that the view has grown that psychological categorization of mental illness is useless at best, and downright harmful, misleading, and pejorative (words having unfavourable meanings) at worst. Psychiatric diagnoses, in this view are not valid summaries of characteristics displayed by the observed” (Rosenhan, 1973). Procedures (What did the Psychologists do to the participants?) 1. 8 sane people attempted to gain admission to 12 different hospitals in five different states in the United States. 2. The ‘pseudopatients’ were 8 sane people - three women and five men (three psychologists, a paediatrician, a psychiatrist, a painter and a housewife - the eighth being Rosenhan himself). 3. They all employed pseudonyms (false names) and those in the mental health profession gave another job to avoid embarrassment to colleagues. They described their life events accurately (both good and bad). None of them had any history of abnormal behaviour. 4. The pseudopatients, very much as a true psychiatric patient, entered a hospital with no knowledge of a date they would get out. Each was told that they would have to get out by convincing the staff that they were sane. 5. The pseudopatients called the hospital for an appointment, stating that they were hearing voices, which were of the same sex and whilst slightly unclear seemed to be saying, “empty”, “hollow” and “thud”. These symptoms were purposefully chosen as their similarity to existential symptoms (the alleged meaninglessness of life) and their absence in psychiatric books. Apart from falsifying symptoms, name and employment, no further pretences were made. 6. Following admission to hospital no further symptoms were ‘acted’ out, and other than some understandable nervousness and tension of being found out, the pseudopatients (pretend patients) behaved perfectly normal. 7. The hospitals varied from old to new, some were research based and one was a private hospital. 88 8. The pseudopatients spent their time talking to the other patients, and making notes of observations of patients and staff on the ward. Initially the notes were done in secret but it soon became apparent that the staff did not really care. 9. There was not much to do on the psychiatric ward and therefore the pseudopatients would engage in conversations with others and would note their observations. Initially this was done in secret, but on realising that no one seemed to mind, this was done openly. Additional Research (cited in original article) study 2: 10.1 After the results of this research were publicised, staff in a hospital that had not received any pseudopatients claimed that it could not happen in their hospital. They were informed that in the next 3 months, one or more pseudopatients would present themselves. 10.2 Staff were asked to rate, on a 10 point scale, their confidence level that the participant was genuine. Judgements were obtained on 193 patients admitted for psychiatric treatment. Perspective : individual differences Method: Participant Observation / Field Experiment 3 advantages of the methodology: Sample (e.g. representative) Internal & external validity/internal & external reliability/ethics & any other issues: 1. Field experiment - natural environment thus high ecological validity, avoids the artificiality of the laboratory experiment. So findings can be generalised to real life settings e.g. other psychiatric hospitals. 2. Participants are unaware that they are taking part in a study, here the staff and real patients, so the influence of demand characteristics are minimized. Therefore we can be confident in the internal validity of the study. 89 3. Sample - sample was 12 hospitals, these were a range of old and new institutions, as well as those with different sources of funding. Results showed little differences between the hospitals, this suggest we can generalise the findings and suggest the same findings would be found in different hospitals. 4. External reliability - Andrews et al (1999) assessed 1,500 people and used DSM IV manual to categorise mental disorders and also ICD (another manual to categorise mental disorders) there was only 35% agreement on what was post-traumatic stress disorder. 3 disadvantages of this methodology: Sample bias/validity – internal & external/reliability internal & external/ethics/gender bias/cultural bias & any other issues: 1. External reliability - Andrews et al (1999) assessed 1,500 people and used DSM IV manual to categorise mental disorders and also ICD (another manual to categorise mental disorders called the international classification of diseases) the 2 methods were reliable and agreement between the 2 systems was 68%. It was also high for a depression diagnosis. This then goes against Rosenhan’s findings. 2. Ethics - lack of informed consent/ deception used on hospital staff, including doctors and real patients. It also discouraged people from seeking help who were concerned about their mental health. 3. Cultural bias - done in America only, other psychiatric hospitals may not operate in this way in other countries, so we can’t generalise these results to Britain for example. British psychiatrists use a different classification system - the ICD (International Classification of Diseases). 4. Internal validity - the pseudopatients were nervous and tense as they had not been in a psychiatric ward before, so this could have been a confounding variable as staff may have seen this as unusual behaviour and thus kept them in for further observation. Findings and conclusions of the study: The pseudopatients exhibited signs of nervousness and anxiety as they were nervous of being found out. All but one of the pseudopatients desired to be discharged 90 immediately. All pseudopatients were admitted in, except in one case, with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Each was discharged with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in remission. Length of hospitalisation ranged from 7 to 52 days, with an average of 19 days. Average daily contact with the psychiatrists was an average of 6.8 minutes per day (based on data from six patients over 129 days of hospitalisation). Whilst at the hospital the ‘real’ patients regularly voiced their suspicions. 35 out of 118 patients made statements such as ‘you’re not crazy’; ‘you’re a journalist’; or ‘you’re a professor checking up on the hospital’. During the research the pseudopatients were given a total of 2,100 tablets - including Elavil, Stelazine and Compazine! Even though most had the same disorder they were given a wide variety of tablets. Nursing records for three pseudopatients indicate that their writing was seen as an aspect of their pathological behaviour (‘patient engages in writing behaviour’) Conclusions: Rosenhan concluded that “It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals. The hospital itself imposes a special environment in which the meaning of behavior can easily be misunderstood. The consequences to patients hospitalized in such an environment – the powerlessness, depersonalization, segregation, mortification and self-labeling – seem undoubtedly counter-therapeutic”. Rosenhan concluded that the failure to detect sanity during the course of hospitalisation may be due to the fact that the doctors were showing a strong type 2 error - that is the physicians were more inclined to call a healthy person sick (a false positive, type 2) than a sick person healthy (a false negative, type 1). 91 Having once been labelled schizophrenic, there is nothing the pseudopatients could do to overcome the label. Once a person is designated abnormal all of his other behaviours are coloured by this label. Indeed the label is so powerful that many of the normal behaviours were overlooked completely or profoundly misinterpreted. Additional Research (cited in original article) Out of 193 admitted patients, 23 were thought to be a pseudopatient by the Psychiatrist. In fact, Rosenhan did not send any pseudopatients to the hospital. Conclusions: Were these 23 patients really sane? Or in the course of avoiding a ‘type 2’ error, had the staff made a ‘type 1’ error and called “crazy people sane”? “Any diagnostic process that lends itself so readily to massive errors of this sort cannot be a very reliable one”. Alternative and complementary research findings: Alternative: The reliability of making an accurate diagnosis has improved. At the time of Rosenhan’s study DSM version 2 was used, nowadays psychiatrists would not be misled by pseudopatients, as a hallucination like hearing voices must be repeated on more than one occasion, as DSM 4 revised version is used, whereas Rosenhan’s colleagues made only one report of hearing voices. (Sarbin & Mancuso, 1980). Spitzer (1976) says the diagnosis ‘Schizophrenia in remission’ given to the pseudopatients is very rare in real patients, he concluded from this that Rosenhan’s pseudopatients were given a discharge diagnosis which is rarely given to real patients, and therefore the diagnosis was due to the pseudopatients’ behaviours and not of the hospital environment. This shows psychiatrists can tell the difference between the sane and insane accurately. Lindsay (1982) obtained video recordings of p’s that had schizophrenia 92 and a group of controls (people who didn’t have it). He showed the video to ordinary people (patients in a general hospital) who rated those in the video. One group was told nothing about the people in the video that were being rated. Findings were that schizophrenic patients were rated as more abnormal than the controls so this shows that being called a schizophrenic is not an unfair label, but that in fact, there is a reality behind the label. Cooper (1983) criticised reliability studies and found that when different psychiatrists use agreed criteria to assess a disorder, when interview procedures for reaching a diagnosis are agreed and psychiatrists are trained to use them, impressive rates of reliability are achieved. Rosenhan’s study cannot account for the fact of why someone shows deviant behaviour in the first place. (MacLeod 1998). Also, if the effects of labels like schizophrenia are so powerful why was it that the real patients in the study weren’t fooled by them? The pseudopatients’ behaviour must have overcome the effects of the labelling of schizophrenic on the observers. Andrews et al (1999) assessed 1,500 people using the DSM 4 (American version of a manual to diagnose people) & the ICD-10 (British & European manual used to diagnose people). He found there was 68% agreement between the 2 systems. This goes against the view that psychiatric diagnosis is unreliable. Complementary research findings: Andrews et al (1999) study (see above) however, also found that there was only 35% agreement between the 2 systems (ICD-10 & DSM 4) for post-traumatic stress disorder. This shows that there is a problem with the diagnosis still of some disorders. Scheff (1966) is supported by Rosenhan, as Rosenhan’s study showed that psychiatric labels like schizophrenia stick in a way that medical labels don’t. Psychiatric labels become self-fulfilling prophecies; everything the patient says and does is interpreted to fit the label, e.g. the normal writing behaviour of the pseudopatients was seen as abnormal! Also, Rosenthal & Jacobsen (1968) examined the self-fulfilling prophecy due to labelling in education. They told teachers some pupils would make rapid progress in a school in California, in reality these pupils 93 were average ability. A year later however, these children did make greater progress than their class mates, so this was due to the way they were treated by their teachers e.g. high expectations of them and presumably the label of them being seen as intelligent pupils. This confirms what Rosenhan found i.e. how important labelling is for the self-fulfilling prophecy. Neisser (1973) supports Rosenhan and refers to the irreversibility of labels. Instead of the pseudopatients being discharged as being ‘normal’, or ‘normal, initial diagnosis in error’, they got the discharge diagnosis of ‘schizophrenia in remission’. This means the psychiatrist can never be wrong, so diagnostic practices can’t be proven wrong! Cooper et al (1972) found New York psychiatrists were twice as likely to diagnose schizophrenia as London Psychiatrists when all showed the same video-taped clinical interviews! A 1973 study showed American psychiatrists had broad concepts (ideas about the disorder) so this could have been why Cooper found those results. Evaluation points of the study: Strengths: Reliable - other researchers have shown the same things, e.g. Scheff on labelling & Andrews with the unreliability of some disorders, using the classification systems to decide if someone has a mental illness. Valid - as the study was done by participant observation you would expect findings to be first hand and valid. Representative sample - used 12 different hospitals in U.S.A. in 5 states, so results can be generalised. Throws light on the nurture side of debate; behaviour seems to be highly influenced by the abnormal environment around the patients, e.g. ignored by many hospital staff. Weaknesses: Reliability of diagnostic procedures has improved, so mistakes in 94 what Rosenhan found would not be found now or more rarely. Individual differences - not everyone will behave according to the labels they are given, people can overcome labels. Experimenter bias - it is likely that the pseudopatients would have gone into the study with a biased view about how the insane are treated and this could affect their views of how the real patients were treated. So it is not objective it is subjective. The study is biased towards the concept of determinism, where we are controlled by events and people around us, but people also have free will how to behave as well. Reductionist - reduces schizophrenia behaviour to an explanation of how labelling affects the patients negatively and how they conform to the label, and their poor environment in hospital i.e. treated badly e.g. assaulted, ignored, staff spend little time with them. Cultural bias - done in U.S.A., can’t generalise to other countries and also ethnocentric - uses an American study to judge how mentally patients are treated generally. Small number of pseudopatients went into the hospitals. Hawthorne effect - the real patients could have changed their behaviour as they may have known they were being observed by researchers of some kind. 95