here - Totton College

advertisement

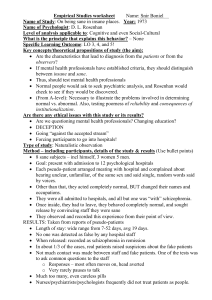

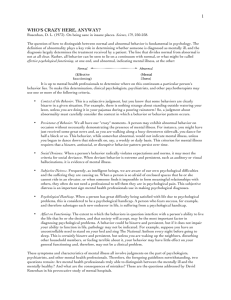

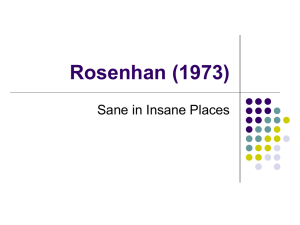

Rosenhan DL (1973) On being sane in insane places. Science 179, 250-8. What could I be asked? 1. Summarise the aims and context of Rosenhan’s (1973) study. (12) 2. Outline the procedures of Rosenhan’s (1973) study. (12) 3. Describe the findings and conclusions of Rosenhan’s (1973) study. (12) 4. Evaluate the methodology of Rosenhan’s (1973) study. (12) 5. With reference to alternative evidence, critically assess Rosenhan’s (1973) study. (12) What do I need to know about the study? aims and context procedure findings and conclusion • Why was this study carried out? What had happened in society recently? Had there been related research already carried out? What were they trying to find out? • What type of study was this? What did they actually do? Where was it carried out? Who took part? How did they measure outcomes? • What did they find out? What conclusions did they draw from this? evaluation of the methodology used • What were strengths and weaknesses of the way this study was carried out? Think about sampling issues, reliability, ethics, ecological validity etc. assessment using alternative evidence • What do other studies suggest about this study? Do they support, contradict it, or perhaps suggest there is something important the researchers didn't think of? Context & aims Definition Validity is ..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Reliability is ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Context Rosenhan begins his paper with the question 'If sanity and insanity exist how shall we know them?'. People have wrestled with the notion of mental illness since long before the birth of psychology. Rosenhan is clear that he is not questioning the existence of mental disorder. As he puts it; 'Anxiety and depression exist. Psychological suffering exists. But normality and abnormality, sanity and insanity and the diagnoses that flow from them may be less substantive than many believe them to be.' In other words Rosenhan is suggesting that although mental disorder exists we are not particularly good at recognising it. Exercise: identify some ways in which we might decide that someone has a mental health problem. ….................................................................................................................................................. .................................................................................................................................................... .................................................................................................................................................... Since the early 20th Century psychological abnormality had been dealt with by means of medical diagnoses. It has been customary to diagnose mental illness from a patient’s symptoms in the same way that physical illness is diagnosed. In 1952 the American Psychiatric Association published its own system, the DSM (Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder). This is now in its 4th edition. Although it is standard practice to make a diagnosis using one of these systems, there have always been concerns about their reliability and validity. All systems assume that we can diagnose a mental health problem like a physical health problem. Rosenhan suggested that one test of the validity of psychiatric diagnosis was whether doctors and other health professionals could recognise that in fact some of their patients had no symptoms at all. This could be tested by using pseudopatients – mentally healthy people who could gain entry to the psychiatric system by faking a symptom then who acted normally. Rosenhan believed that if the mental health system was capable of valid diagnosis, professionals would soon spot pseudopatients. Contextual Research An earlier study by Temerlin (1968) used a confederate to test the validity and reliability of diagnoses. Psychiatrists were shown a videotape of a confederate who played a mentally healthy mathematician. Prior to viewing the tape a prestigious doctor informed the psychiatrists that they were about to view an interesting case, because the man looked neurotic but was actually psychotic. Participants then selected their diagnosis from a list, including psychotic, neurotic and mentally healthy. 60% of psychiatrists selected psychotic. This suggests that diagnoses can be invalid as the man was diagnosed with a psychosis when he showed behaviour consistent with a state of good mental health. There are some issues with this study; rather than testing labelling effects, Temerlin may have been testing conformity, which would not affect doctors confidentially diagnosing patients. Rosenhan wanted to run an experiment which tested the validity of diagnoses made using the DSM, in an more ecologically valid setting. Aim This was a pseudopatient study looking at the success of the mental health system to spot pseudopatients at the point of diagnosis and during hospitalisation. The first specific aim was to see whether they would be identified as 'sane' when they presented themselves for diagnosis. The second specific aim was to record their experiences as psychiatric in-patients. Method Sample Size: Experiment 1Experiment 2- This was a study because it was held in the natural environment. The IV (Independent Variable) was … Sampling method: Experiment 1- The DV (Dependant Variable) was… Experiment 2How were they recruited? Setting: Experiment 1Experiment 2Sample characteristics: Experiment 1- Exercise: suggest why it was important to use a range of hospitals. ....................................................................... ………………………………………………….................... Experiment 2- ………………………………………………….................... ………………………………………………….................... Procedure The pseudopatients Eight pseudopatients took part in the study. Five were men and three women. Three were psychologists, one a psychology student and one a psychiatrist. The others were not mental health experts; one was a paediatrician (a medical doctor specialising in treating children), another a housewife and the other a painter and decorator. All used false names so that they would not have a diagnosis on their own medical records after the study. The mental health professionals also gave false information about their occupation so that they would not receive any special treatment. Faking the symptom Each pseudopatient called a hospital then attended an appointment where they reported hearing voices. In each case the voice was the same sex as the pseudopatient and unfamiliar to them. The voices were sometimes unclear but the words ‘empty,’ ‘hollow’ and ‘thud’ could be made out. Apart from the voices they gave accurate descriptions of their mental state. Exercise: why was it important for all patients to fake the same symptom? ….................................................................................................................................................. .................................................................................................................................................... Being an inpatient Once admitted to the hospital psychiatric wards they acted normally with staff and patients. They accepted (but did not take) medication from staff. When asked they reported no further symptoms. In three hospitals the pseudopatients recorded the number of patients who expressed doubts that they were genuine. In four hospitals they attempted to ask doctors and nurses questions and recorded their responses. Exercise: What were they testing as inpatients? …………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. A follow-up study A follow-up to the main study took place at another hospital whose staff had expressed doubt that they would be fooled by pseudopatients. They were informed that one or more pseudopatients would present themselves over the next three months. Staff rated all new patients on a 1-10 scale for how likely each new admission was to be a pseudopatient. In fact no pseudopatients approached them in this time; the idea was to record how many real patients were falsely judged to be pseudopatients. Findings Headline figures In 100% of cases the pseudopatient was immediately admitted to hospital. The length of stay ranged from 7-52 days (average 19 days). 11 patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and one with manic depression. Whilst in hospital no doctors or nurses questioned the genuineness of the pseudopatients. However, of the 118 patients in the three hospitals where patient responses were recorded 35 (30%) challenged the pseudopatients. Exercise: In the four hospitals staff responses to questions were recorded. Outline the findings shown in the above table. …..................................................................................................................................................... ....................................................................................................................................................... Plot this data into a graph. Qualitative data Qualitative data was available in the form of notes taken by the pseudopatients and hospital staff. These illustrate how staff interpreted the behaviour of the pseudopatients in line with their beliefs that they were mentally disordered. One nurse recorded daily that her pseudopatient ‘engaged in writing behaviour,’ seeing this as a compulsive behaviour (in fact the pseudopatient was keeping notes). Another interpreted the bored pacing of a Recap Recap pseudopatient as nervousness. One patient mentioned how in childhood he was closer to his mother but more recently had got on better with his father. In his notes this was presented as follows: ‘…manifests a long history of considerable ambivalence in close Recap relationships, which begins in early childhood. A warm relationship with his mother cools in adolescence. A distant relationship with his father is described as becoming very intense.’ How does this make family life sound? ….................................................................................. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Is there any real evidence for this? Yes [ ] No [ ] Now check your understanding by summarising the study in the boxes below: The follow-up study Further data came from the follow-up study. Over the three months of the study 193 genuine patients and no pseudopatients were admitted. 41 were judged with a high level of confidence to be a pseudopatient by at least one member of staff. In 23 cases at least one psychiatrist and in 19 cases a psychiatrist and another staff member believed they were dealing with a pseudopatient. Conclusion The major conclusion of the study was that even experienced mental health professionals [delete one] could/couldn’t reliably distinguish between real and false patients. Recap Faking a single symptom on a single occasion [delete one] was/was not sufficient to receive a psychiatric diagnosis. Furthermore, once in the mental health system, patients’ normal behaviour was interpreted as symptoms of their disorder. This provides further evidence to suggest that the validity of psychiatric diagnosis was [delete one] good/poor. Rosenhan did not use his data to criticise the competence or conduct of doctors or nurses. Instead he blamed the poor results on the ‘system’ of diagnosis. Recap Aim • • Procedure • • Findings • • Conlcusions • • Alternative Evidence Temerlin (1968) Temerlin (1968) used a confederate to test the validity and reliability of diagnoses. Psychiatrists were shown a videotape of a confederate who played a mentally healthy mathematician. Prior to viewing the tape a prestigious doctor informed the psychiatrists that they were about to view an interesting case, because the man looked neurotic but was actually psychotic. Participants then selected their diagnosis from a list, including psychotic, neurotic and mentally healthy. 60% of psychiatrists selected psychotic. This suggests that diagnoses can be invalid as the man was diagnosed with a psychosis when he showed behaviour consistent with a state of good mental health. This Rosenhan’s findings that Psychiatric diagnoses are invalid. Temerlin however, lacked ecological validity, which highlights the strength of Rosenahn’s field study. Temerlin’s study also highlights the importance of in Rosenhan, which assured that measures were testing diagnoses made using the DSM, rather than any extraneous variables such as conforming to colleague’s opinions. Slater (2003) Slater (2004) claims to have presented herself to nine hospital emergency rooms with the same symptom as Rosenhan's pseudopatients. In most case she reports receiving a diagnosis of psychotic depression. However, according to Moran (2006) a number of experts have challenged the truthfulness of Slater's claims, so the credibility of her evidence is unclear. Slater’s replication shows strong findings are for Rosenhan, suggesting that his , in that a diagnosis of mental illness was wrongfully made. However, Slater presented the same symptoms and was given a different diagnosis, which questions the reliability of diagnoses. This may be due to changes in the DSM, which have tightened criteria for many mental illnesses, particularly for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This demonstrates that Rosenhan’s study was in improving the diagnostic system. Slater also highlights the importance of , such as standardised measures and criteria, which Rosenhan implemented. Changes to the DSM/ ICD There have been important changes to systems of psychiatric diagnosis since Rosenhan’s study. At the time the standard system was the 2nd edition of the DSM (DSM-II). We are now on the 4th edition with revisions (DSMIV-TR). One of the major reasons for continuing to work on newer versions of systems like this is to improve the validity of diagnosis. One way that newer versions have tightened up on diagnosis is in specifying that symptoms must occur with particular frequency or over a particular period. For example in the DSM-IV system, hearing voices must now take place for over a month before they could be used as a basis for diagnosing schizophrenia. Diagnostic systems are also tested for validity by measuring the concurrence (agreement) between two different manuals, for example the ICD (European diagnostic manual) and DSM. This is called concurrent validity, and tests show it is quite high, at 70%. Changes in the diagnostic criteria demonstrate the of Rosenhan’s study. By tightening the criteria for schizophrenia, Rosenhan’s patients could not be diagnosed with schizophrenia today, as they did not experience symptoms for over a month. What can we conclude from alternative evidence? Later research strongly Rosenhan’s finding that psychiatric diagnoses are fairly reliable, but lack validity. Temerlin also supports Rosenhan’s other findings of labelling effects. However, Rosenhan’s results may not to a modern sample because of changes in the DSM partially inspired by his study. Modern replications of Rosenhan lack validity because they have not been carried out with such strict controls.