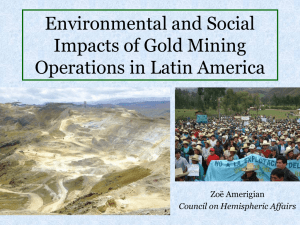

Best Practice Mining in Colombia

advertisement