Safe Injection Technique

advertisement

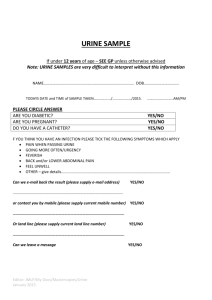

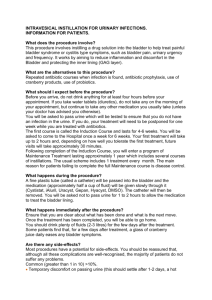

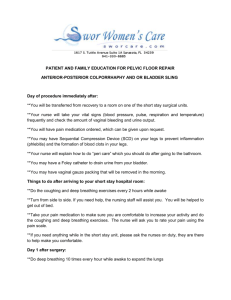

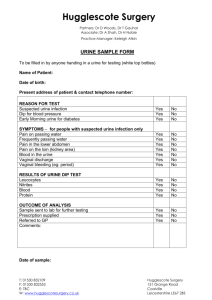

Male & Female Catheterisation, MSU, Urinalysis & Pregnancy Testing Aims To demonstrate female and male catheterisation and give Medical Students knowledge about the procedure. To demonstrate how to collect a mid-stream specimen of urine (MSU). To demonstrate how to perform urinalysis. To demonstrate how to perform pregnancy testing. Learning outcomes By the end of session students will be able to: • Explain the principles of the procedures. • Identify the equipment required for MSU, urinalysis, pregnancy testing and catheterisation. • Demonstrate understanding of male and female anatomy during simulated practice. • Demonstrate catheterisation on manikins using an aseptic technique. • List the possible complications associated with catheterisation. • Describe how to gain informed consent from patients undergoing the procedures. • Explain how to complete the relevant documentation for each procedure. • Apply standard infection prevention measures during simulated practice. Male and Female Catheterisation Introduction Catheterisation is the insertion of a tube into the bladder using an aseptic technique. The tube is inserted to either drain or instil fluid. Supra-pubic is chosen if it is to be permanent or cannot be inserted via the urethra. Anatomy The female urethra is 4-6cm long. Male urethra is 18-20cm long. Urethral catheterisation can cause bruising and trauma to the urethral mucosa which then acts as entry points for micro-organisms into the blood and lymphatic system. Scar tissue is easily formed as a result of trauma. The bladder lies just behind the symphisis pubis. When empty the bladder collapses into a pyramid shape. As urine accumulates it expands and becomes pear shaped. A reasonably full bladder holds 500ml. It can hold 1 litre if necessary. During micturition the detrusor muscles in the bladder wall contract and compress the bladder pushing urine into the urethra. The neck of the bladder is closed by two rings of muscle – the internal sphincter (involuntary control) and external sphincter (voluntary control). Stimulation from the CNS keeps the external sphincter fibres contracted except during micturition. When 250ml of urine has collected, stretch receptors in the bladder walls are stimulated and excite sensory parasympathetic fibres, which relay information to the spine and then to the thalamus and cerebral cortex. Parasympathetic motor neurons are excited and contract the detrusor muscles in the bladder. Bladder pressure increases and the internal sphincter opens. When urine enters the urethra, somatic motor neurons supplying the external sphincter are inhibited allowing the sphincter to open and urine to flow out, assisted by gravity. The brain can override the micturition reflex. Male Anatomy Female Anatomy Reasons for Inserting a Urinary Catheter To empty the bladder prior to surgery. To monitor renal function post-op To drain urine when the patient is in urine retention. To closely monitor urine output in critically ill patients. To instil fluid, irrigation or cytotoxic drugs. For bladder function tests to be performed. As a last resort for urinary incontinence when all other methods have failed. Possible Contraindications Recent urological surgery Trauma to the pelvis or abdomen Cancer in the lower urinary tract Haematuria of unknown cause Catheter Selection PTFE (Teflon) max 4 weeks Hydrogel- max 12 weeks Silicone - max 12 weeks Intermittent catheters Catheter Size Catheters are measured by Charriere gauge (CH). The charriere is the external diameter of the catheter 1/3 of a millimetre, for example: CH No. = external diameter in mm 3 Therefore a 12ch catheter has an external diameter of 4mm. Use the smallest possible size, large catheters can be associated with bypassing, pain and blockage. Sizes 12 – 14 are used for routine drainage Sizes 16 is used if there is debris in the urine Size 18 should only be used when blood clots are present Potential Problems Infection and sepsis UTI is the most common infection acquired in acute hospitals and long-term care facilities. Aseptic technique and universal precautions must be used and urine samples sent for testing if infection is suspected. Encrustation and blockage; The cause of the blockage must be identified and the appropriate catheter maintenance solution used. Sodium chloride to wash out debris e.g. blood, mucus, or pus. Citric acid for dissolving crystals. Mandelic acid to reduce micro-organisms Urine not draining The catheter may be in the wrong place, deflate the balloon and gently reposition. The drainage bag may be positioned above the level of the bladder preventing good flow. Drainage tubing may be kinked, check position and tubing. Catheter may be blocked by debris, gently flush with sterile saline. Haematuria May result from trauma post-catheterisation, infection, prostate enlargement, calculi, carcinoma. Observe and document severity, encourage fluids, seek medical advice if necessary. Urine bypassing the catheter May be due to infection - obtain CSU. Bladder spasm- consider use of medication. Constipation- increase fluid intake and dietary fibre. Incorrect position of drainage system - position below bladder. Bladder irritation/pain The eyelets of the catheter may be occluded by urothelium due to hydrostatic suction – raise the bag above the level of the bladder for 15 seconds. Catheter retaining balloon will not deflate Valve port may be compressed or their may be a faulty mechanism. Check there are no external problems, aspirate valve port slowly, and try injecting a small volume of sterile water and then aspirating again. If this fails seek medical advice do not cut the catheter as it may retract into the bladder. Advice to Patients with Urinary Catheters Hand washing. Strict hygiene when looking after catheter. Explain how to empty the catheter and change bags. Encourage fluid intake of at least 1.5 – 2 litres fluid per day. Give contact numbers in case of problems and refer to district nurse. Equipment Required for Urinary Catheterisation Silver trolley Apron Alcohol gel 2 pairs of sterile gloves Catheterisation pack 2 catheters – correct size and type 10ml water for injections and 10ml syringe Sterile cleansing solution Sterile gauze Drainage bag and stand Sterile instillagel (11ml for men / 6ml for women) (NB Ensure you check expiry dates on all equipment used) Before you begin the procedure Introduce yourself Obtain informed consent Place a waterproof sheet under the patient. Assist the male patient to lie in a semi-recumbent position Assist the female patient to lie down with their knees flexed and legs apart Cover the patient and maintain privacy and dignity Reassure the patient Wash your hands and prepare your equipment The Procedure Once the patient is prepared and comfortable wash your hands and put on the apron Clean your trolley Place equipment on the bottom shelf, checking all expiry dates and seals as you do so. Take the trolley to the patient’s bedside, ensure your patient is prepared and comfortable Clean your hands using alcohol gel Using aseptic technique open catheter pack onto the top of the trolley and place other equipment onto the pack Expose the genital area, wash hands and put on sterile gloves For males retract the foreskin, cleanse shaft, glans and the urethral meatus using normasol For females separate the labia minora to expose the urethral meatus using normasol Clean away from the urethral orifice using single downward strokes For males arrange the sterile drape so the penis passes through the hole and use gauze to hold behind the glans For females place the sterile drape under the patient Insert the anaesthetic jelly into the urethra and leave to take effect for 3-5 minutes (11ml for men / 6ml for women) Wipe away any excess gel, dispose of gloves, wash and dry hands and reapply new sterile gloves (Pratt, 2007) Place the catheter in the receiver For men use the gauze to hold the penis at an angle between 60 – 90 degrees For women use the gauze to separate the labia Introduce the tip of the catheter into the urethra and insert fully up to its bifurcation point to make sure the catheter has cleared the prostatic bed and is in the bladder Ask the patient to take deep breaths to ease discomfort Once urine flows inflate the balloon and connect to drainage system For men ensure the foreskin is replaced over the glans to prevent constriction and oedema Dispose of waste, wash your hands, ensure the patient is comfortable and dry Documentation The following should be recorded in the patient’s notes: Time and date Clinical reason for procedure Informed verbal consent Aseptic technique used Instillagel used Catheter size, type and expiry date Any problems encountered Amount of urine drained Record urine output on the fluid balance chart Complete Care Pathway Catheter Care Pathway Catheter Care Removal of Urinary Catheters Explain the procedure and obtain informed consent Wash hands and apply gloves, Use saline to clean the meatus and catheter and then change gloves, Remove water from the balloon using a 10ml syringe Ask patient to breathe in and out and when they exhale withdraw the catheter. Clean the meatus and make the patient comfortable. Post Catheter removal – Ward Care Catheters are either removed at midnight so the patient goes to the toilet on waking or early morning so that problems can be dealt with during the day. Ensure the patient can get to the toilet when needed and give a supply of liners, ask the patient to use a separate one each time they pass urine. Encourage fluid intake and ensure urine passed is documented on the fluid balance chart. Ensure the patient is passing urine easily and in good volumes (above 100mls each time). If patient is having difficulty use a bladder scanner to assess residual urine. Document care given in patients notes. Mid-stream Specimen of Urine (MSU) & Urinalysis Introduction The Mid-stream urine (MSU) test is carried out to check for infections. Infections can cause a lot of bladder problems so it is important that these are ruled out first. Background Physiology The kidneys filter approximately 180 litres of plasma per day. The final volume of urine produced is approximately 1 – 1.5 litres. The processes of ultrafiltration, tubular reabsorption and tubular secretion ensure that vital substances such as glucose, amino acids and electrolytes are conserved as required and waste products such as urea and creatinine are excreted. Water maybe conserved or excreted as required. Normal Urine Urine is a straw-coloured clear fluid. When urine is becoming concentrated, it becomes darker and more yellow. Urine may have no smell or may have a slight aroma. This may alter as a result of disease, concentration or length of time it has been stored in the bladder. Urine is slightly acidic – pH 5 – 6. Urine’s normal composition includes water, urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium, protein, small traces of protein and glucose and cellular components. Urinalysis (Point of care analysis) Introduction Urinalysis is used as a screening and/or diagnostic tool because it can detect different metabolic and kidney disorders. Often, substances such as protein or glucose will begin to appear in the urine before patients are aware that they may have a problem. It is used to detect urinary tract infections (UTI) and other disorders of the urinary tract. Basic urinalysis should include observing the urine’s colour and consistency. Any cloudiness or debris may indicate presence of abnormal cells or disease. The aroma of the urine should be documented. A ‘fishy’ aroma may indicate infection whereas a ‘pear drop’ aroma may indicate the presence of ketones. All of the above should be considered in the context of the patient’s clinical condition, urine output and fluid balance records. Reagent Sticks Reagent sticks are plastic or paper strips impregnated with chemicals. These should be immersed in the urine sample and read against the reference guide supplied to provide an indication of the presence of a certain substance. Reagent sticks or dipsticks are useful in preliminary patient assessment. A common range of tests form part of general urinalysis. These tests may include: Blood / haemoglobin – the presence of which may indicate trauma Erythrocytes – presence of this may indicate bleeding in the genitor-urinary tract, kidney stones or infection White blood cells – this may indicate infection pH Glucose Ketones – presence may indicate keto-acidotic states or starvation Protein – may indicate, hypertension, kidney or heart dysfunction or infection Equipment required for urinalysis Urine dipsticks Gloves Sterile receiver Disposable towel Apron The Procedure Obtain verbal informed consent Check manufacturers instructions and check expiry date of reagent sticks Wash hands, put on gloves and apron Collect an MSU or catheter specimen from the patient using a sterile receiver Remove reagent stick from container and immediately replace cap Immerse the reagent stick into the urine, the duration of immersion will vary according to manufacturer’s instruction Wipe the edge of the reagent stick on the rim of the receiver to remove any excess urine. Dab the back of the test strip on an absorbent towel Read the reagent strip against the reference guide provided. Dispose of urine and reagent strip appropriately Remove gloves and apron and wash hands Document results in patient notes and obtain sample for microbiological analysis if required Mid-stream Specimen of Urine (MSU) The MSU must be: Appropriate to the patient’s clinical presentation Collected at the right time Collected in a way that minimises contamination Collected to minimise risk to all staff (including laboratory staff) Documented clearly Transported appropriately Urine Samples Urine is frequently collected for microbiological and/or biochemical investigation. It is commonly collected for testing levels of particular metabolites or presence of particular drugs or drug metabolites and toxicology screens. Microbial culture and antimicrobial sensitivity. Where a sample is to be microbiologically tested, an MSU is required. This involves taking a ‘middle’ sample whilst urine is being voided. This avoids the initial and end stages of the void which reduces the risk of contamination of the sample from bacteria that colonises the distal urethra as these bacteria are washed away with the initial urine flow. Advice to Patients requiring MSU MSU is indicated in adults and children who are continent and can empty their bladder on request (Gilbert, 2006). Most patients require advice beforehand to ensure that a ‘middle’ sample is collected. Hygiene advice must be given to reduce risk of contamination from hands or the genital area. Uncircumcised men should retract their foreskin before micturition. Women should be advised to part the labia. It is widely agreed that a strong urine flow will clear bacteria from the urethral meatus therefore it is suggested that a sample be obtained when the bladder is full to result in the least contaminated sample. Equipment required for MSU Soap and water Sterile specimen pot Gloves Apron Appropriate investigation request form The Procedure Obtain patient informed consent and assess the level of assistance the patient may require Instruct or assist patient to wash hands and attend to genital hygiene Provide information on retracting the foreskin / parting the labia Instruct the patient to direct the first part of the void into the toilet Ask the patient to collect the middle part in the sterile pot Ask the patient to void the remaining urine into the toilet Instruct the patient to wash hands Label the sample, complete request from and document in the patient notes Pregnancy Testing Introduction A pregnancy test attempts to determine whether or not a woman is pregnant. Modern pregnancy tests look for chemical markers associated with pregnancy. These markers are found in urine and blood, and pregnancy tests require sampling one of these substances. The first of these markers to be discovered, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), was discovered in 1930 to be produced by the trophoblast cells of the fertilised ovum (blastocyst). While hCG is a reliable marker of pregnancy, it cannot be detected until after implantation this results in false negatives if the test is performed during the very early stages of pregnancy. Most chemical tests for pregnancy look for the presence of the beta subunit of hCG in blood or urine. hCG can be detected in urine or blood after implantation, which occurs six to twelve days after fertilization. Quantitative blood (serum beta) tests can detect hCG levels as low as 1 mIU/mL, while urine tests have published detection thresholds of 20 mIU/mL to 100 mIU/mL, depending on the brand. Radiology Prior to a diagnostic imaging procedure, it is essential that any female of reproductive age (between 12 and 55 years although local trust policy and guidance may differ) presenting for an examination involving exposure of the pelvic area or the administration of radioisotopes is asked if she might be pregnant. Where possible, an examination should be scheduled within 28 days of the onset of the last menstrual period. Where a high dose procedure is proposed, for example a pelvic CT or barium study, local policy may require the procedure to be completed within 10 days of the onset of the menstrual period. If the woman cannot exclude the possibility of pregnancy then it should be ascertained if her period is overdue. Advice should be sought from the clinician authorising the investigation as to whether the investigation is justified by being of indirect benefit to an unborn child, for example an emergency procedure. If the period is not overdue (within 28 days of the onset of the last menstrual period) then a urine or serum test for pregnancy may be performed prior to the examination. These tests are highly sensitive. The Equipment Please refer to local arrangements. At GEH a Clearview hCG II Pregnancy detection test is used. The Procedure Pregnancy Tests are to be carried out following the manufacturers’ instructions. For Clearview hCG, see below. References Bardsley, A. (2005) Use of lubricant gels in urinary catheterisation. Nursing Standard. 20, 8 BAUN (British association of urological nurses) (2000/2001) Guidelines for female urethral catheterisation using 2% lignocaine gel (Instillagel) Printed by CliniMed Limited. Bruck, L., Donofrio, J., Munderi, J., Thompson, G. (nk) Anatomy and Physiology made incredibly easy. London: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Dougherty, L. Lister, S (2004) The Royal Marsden Hospital manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Gilbert, R. (2006) Taking a midstream specimen of urine. Nursing Times; 101: 18, 22-23. Graham, J.C, Galloway, A. (2001) The laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Journal of Clinical Pathology; 54: 911-919 Higgins, C. (2000) Microbiology testing. In: Understanding Laboratory Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell Science. Leaver, R.B. (2007) The evidence for urethral meatal cleansing. Nursing Standard; 21: 41, 39-42. NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (2004) Best Practice Statement. Urinary Catheterisation and Catheter Care. www.nhshealthquality.org Pratt, R.J. (2007) Epic 2: National evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. Journal of Hospital Infection; 65 suppl 1; s1-64 RCN (2005) Good practice in Infection Prevention and Control: Guidance for Nursing Staff. London: RCN. RCN (2006) Best Practice Guidance on Pregnancy Testing prior to diagnostic imaging. http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/78707/003063.pdf accessed March 2010 RCN (2008) Catheter Care. RCN Guidance for Nurses. London RCN Richardson M. (2006) The Urinary System. Part 4 – Bladder control and micturition. Nursing Times. 102, 43 Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust (2004) Royal Marsden Hospital Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures. Sixth Edition. Eds Dougherty, L., Lister, S. London: Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust / Blackwell Publishing Skills for Health. www.tools.skillsforhealth.org - accessed March 2010. CHS 7 Obtain and test specimens from individuals Skills for Health / RCN (2008) www.tools.skillsforhealth.org - accessed March 2010. Continence Care – National Occupational Standards (NOS). Tew, L. et al (2005) Infection risks associated with urinary catheters. Nursing Standard. 20, 7