Archaeological Report on 1837 Farm Midden

advertisement

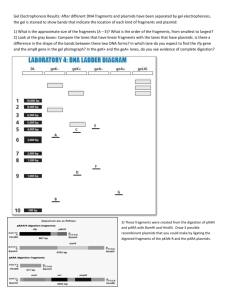

1837 Fordon Farm Appendix A: Garden Area Midden History and physical setting: The Fordon family has occupied this property continuously from 1837 to the present time. Since the early 1980s the family has maintained a flower, fruit and vegetable garden on a site between the back yard and a small fruit tree grove. The current garden is approximately half its former length (East to West). It is rototilled twice each year. The exposed soil exhibits many fragments of glass, ceramics, metal, bone, etc. which would seem to indicate the presence of a past refuse dumping area or midden. The actual boundaries of the midden are not currently known, the only visible area is the exposed soil of the garden. William Edward Fordon (born in 1946 and grew up on the farm) remembers this general area (East to West, beyond the current boundaries of the garden) being littered with farm and household trash at one time. There is a subsurface brick foundation near the garden (approximately ten feet to the Northwest). 1 Exposed midden area 1 Fordon family garden, looking to the South East. Photographed 28 April 2003 by Michael Fordon. 2 Subsurface brick foundation wall, discovered in the late 1990s while digging a leach line. The artifacts, collecting and quantifying: In an attempt to supplement the documentary history of the farm an effort was made in 2008-2009 to recover artifacts from the midden. All artifacts were surface collected and show a moderate to high degree of weathering. 3 A freshly collected batch of artifacts, before cleaning and after. This batch contained clear and colored glass, fired clay rubble, decorated and plain ceramics, coal, coal ash, building materials, metal, plastic and bone fragments. 2 3 Subsurface brick foundation wall. Photographed circa late 1990s by Michael Fordon. Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. List of artifacts collected from garden area midden Ceramic, transferware, blue: (also flow blue and others) 87 fragments Ceramic, transferware, red: Blue pebble (fish tank?): 3 whole 3 fragments Clay pipe pieces: 7 fragments Ceramic, transferware, black: 12 fragments Glass, clear: 218 fragments 2 whole Ceramic, transferware, clear / faded: 2 fragments Glass, clear, painted: 1 fragment Ceramic, transferware, yellow: 1 fragment Glass, colored white: 18 fragments Ceramic, white porcelain?: (some decorated) 32 fragments Glass, colored pink: 28 fragments Ceramic, plain white: (ironstone and others) 204 fragments Glass, colored yellow: 1 fragment Glass, colored pale green: 5 fragments Ceramic, misc. decorated: 22 fragments Glass, colored green: 3 fragments Ceramic, shell edge, blue: 9 fragments Glass, colored dark green: 9 fragments Ceramic, shell edge, green: 2 fragment Glass, colored light blue / aqua: 70 fragments Ceramic, yellow ware: 12 fragments Glass, colored blue: 26 fragments Ceramic, glazed: (earthenware/stoneware) 70 fragments Glass, colored brown: 50 fragments Ceramic, glazed, decorated: (earthenware/stoneware) 2 fragments Glass, colored dark (?): 1 fragment Glass, colored dark, almost black: 15 fragments Ceramic, unglazed: (earthenware/stoneware) 25 fragments Coal, unburned: 38 fragments Ceramic, doll / figurine face: 1 fragment Coal, burned / ash: 36 fragments Plastic, misc.: 11 fragments Stone, square stone: 1 fragment Plastic garden planting tags: 4 whole 12 fragments Brick, glazed: 7 fragments Clay rubble, white: 18 fragments Rubber: 1 fragment Fired clay rubble, tan / orange: 159 fragments Textile: 1 fragment Fired clay rubble, dark red: 18 fragments Tin / aluminum scraps: 6 fragments Mortar / concrete: 13 fragments Metal squeeze tube remains: 4 fragments Metal, modern pieces: 9 fragments Metal, antique pieces: 21items Metal, green four hole button: 1 whole Metal / plastic, electric fence wire cap?: 1 fragment Coin, 1800 5 cent piece: 1 whole Coin, play money, 10 cent piece: 1 whole Beads: 2 whole Misc. unidentified, stone?, concrete?, ash?: 14 fragments Total artifacts collected: 1,402. Faunal remains, misc. bone: 54 fragments (9 showing butchery marks) Faunal remains, teeth, bovid: 2 fragments Faunal remains, teeth, pig: 5 fragments Faunal remains, teeth, unidentified: 6 fragments Faunal remains, shell: 16 fragments The artifacts, personal items and miscellaneous: 4 Seen here is a collection of miscellaneous artifacts recovered from the midden area showing the wide diversity of objects discarded there. Items include a bead, green metal button, an American five cent piece dated 1800, glass lens, various fragments of porcelain and plain and decorated ceramics, plastic soldier figurine, a large piece of a Pond’s cream jar (probably early 20th century5), and an intact clear glass Prince Matchabelli perfume bottle (probably early-mid 20th century6). The large white ceramic fragment at bottom middle bares the manufacturer’s mark, “Ironstone China O.P.Co.” Ironstone is a type of ceramic product valued for its durability. It was first developed in the early 19th century in England by mixing finely ground iron slag into the normal pottery making process.7 O.P.Co. stands for the Onondaga Pottery Company located in Syracuse, New York. This particular manufacturer’s mark was probably in use from 1874-1893.8 4 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. So dated because it seems to match pictures of Pond’s jars seen in advertisements from approximately 1915-1925 (available 21 June 2009: http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/eaa/browse/ponds/ ) 6 This bottle dates to circa 1926-1950s. It is difficult to date more precisely without knowing which line of Prince Matchabelli perfume this is –the most likely candidates are Autumn Gold (1948), Stradivari (1950) and Wind Song (1952). (See: http://reviews.ebay.com/Vintage-Prince-Matchabelli-Perfumes_W0QQugidZ10000000002832729 and http://www.perfumeprojects.com/museum/marketers/Prince_Matchabelli.shtml ) 7 Freeman, Larry, Ironstone China, Century House, Watkins Glen, NY, 1954, page 4. 8 Kowalsky, Arnold and Kowalsky, Dorothy, Encyclopedia of marks on American, English, and European earthenware, ironstone, and stoneware (1780-1980), Schiffer Publishing, Pennsylvania, 1999, page 54. 5 The 1800 American five cent piece is known as a “draped bust half dime” with an heraldic eagle on the reverse. This coin was produced from 1800-1805 and is a mix of silver (89%) and copper (10%).9 Seen here is an example in much better condition: 10 11 Fragments of clay tobacco pipes recovered from the midden. (left) Detail of pipe fragment showing an ornamented stem. (right) For centuries, use of the clay pipe was a popular method for smoking tobacco. Pipes were usually produced in a mold and most were relatively plain. Some pipes were elaborately decorated or formed in whimsical shapes. Discarded bits of pipes are common finds in archaeological digs in the Eastern United States.12 During the 19th century, which is the period most of the midden artifacts date to, clay pipes were cheap 9 Available 29 April 2009. http://www.coinlink.com/CoinGuide/us-type-coins/draped-bust-half-dimeheraldic-eagle-1800-1805/ 10 Available 29 April 2009. http://www.coinlink.com/CoinGuide/us-type-coins/draped-bust-half-dimeheraldic-eagle-1800-1805/ 11 Photographed by Michael Fordon, June 2009. 12 Davey, P. J., “Editorial,” The archaeology of the clay tobacco pipe, vol.II: The United States of America, BAR International Series 60, Oxford, England, 1979, page 1. and common. These artifacts are the only indicators of tobacco consumption on the Fordon farm in the 19th century and illustrate indulgence in a widely practiced leisure activity. The artifacts, faunal remains: 13 Seen here is a selection of faunal (animal) remains recovered from the midden, including fragments of fresh water clam shells, teeth (some identified as pig and cattle14) and miscellaneous bone pieces. Photo on the right shows bones exhibiting clean, straight cuts indicative of butchery or food preparation. These artifacts are almost certainly remnants of meals and tell us something of the family’s meat preferences. The shells are of special note as the fresh water clam is no longer common as a local food item.15 In the 19th century the Geneva newspapers advertized oysters and fresh water clams for sale in large quantities. There are over 200 native species of freshwater mussels in eastern North America and they were aggressively harvested in the late 19th and early 20th century.16 13 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. Author’s email correspondence with Adam Dewbury (Graduate Student, Anthropology Dept., Cornell University), 23 December 2008. 15 Although the most likely explanation for the shells is that they were refuse from meals, they could also be remnants from agricultural applications. Shells were finely ground and used as a dietary supplement for poultry and also as a manure adding lime to the soil. See: Robinson, J., Principles and Practice of Poultry Culture, New York: Ginn and Co., c1912, pages 200-201. And: Singleton, J., “On the improvement of land by the use of shell-marle,” American Farmer, Baltimore, vol.2, issue 15, 7 July 1820, page 114. 16 Available 19 June 2009: http://www.assemblage.group.shef.ac.uk/1/peacock.html 14 The animal teeth are also interesting. They are most likely discarded bits left over from butchery and/or food preservation practices. In the 19th century home/farm slaughtering of livestock was a common occurrence. As much of the animals as possible was utilized, including the meat, fat, tongue and jowls of the head. Every thrifty farmer slaughtered his own hogs and filled barrels with salt pork, tubs with lard, and a smokehouse with hams and sides of bacon to cure. “Hog-killin” was an important period in the farm economy of the times. ...Not only pigs but often oxen and cows… had been fattened for slaughter… So pickled, smoked, and potted, meats of the several kinds were kept from butchering time to butchering time.17 The artifacts, glass: The midden contains a large number of glass shards, both clear and colored. These fragments represent a wide array of products including decorative items, toiletry items and bottles and jars of many types. Fragments from clear glass jars with wide diameters probably represent late 19th to early 20th century food preservation and storage practices. The majority of the shards probably represent items related in some way to food and beverage consumption / storage / preservation. 18 17 Hedrick, Ulysses Prentiss, A History of Agriculture in the State of New York, New York State Agricultural Society, 1933, page 220. 18 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. The artifacts, ceramics: 19 20 On the left is a selection of glazed ceramic fragments (mostly stoneware) recovered from the midden area. On the right are examples of intact stoneware products (not from the midden). The midden contains a wide variety of shards of earthenware and stoneware. These are both fired clay products usually formed into vessels for food preparation, consumption and storage. Earthenware was cheaper, more porous and less durable. Stoneware was made of clay which was fired at a high temperature. It was sealed inside and out with glaze, more scratch resistant and absorbed less moisture.21 For the most part these items were utilitarian and both types of ceramics were common in the 19th century and even into the early 20th century. The fragments from the midden exhibit multiple colors and glazes, including salt glaze and others. The size and shape of the fragments suggests containers of varying volume and purpose. Certainly jugs, water coolers, crocks and jars would have been among the types of objects these items represent. 19 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. Available 16 June 2009: http://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2008/04/30/drinking-wine-and-otherspirits-in-jane-austens-day/ 21 Available 19 June 2009: http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_is_the_difference_between_stoneware_dishes_earthenware_dishes 20 22 Seen here is a selection of decorated ceramic shards recovered from the midden area including blue, red and black transferware. These materials most likely represent objects related to food and beverage presentation, consumption and tableware display as a symbol of status. Pieces such as these were less utilitarian and more formal –perhaps being used for tea service, family dinner and special occasions. Transferware or transfer print ceramics originated in England in the mid 18th century. They are produced by applying an engraved image onto a ceramic surface before firing in low heat.23 The result is a crisp, detailed design on the final product. If acquired new, transferware was pricier than hand painted, sponge or shell edge items. Although tableware makes up the vast majority of ceramic products decorated in this manner, there were also toiletry items, vases, candle holders and other miscellany. The patterns on the shards exhibit geometric designs, floral and animal motifs. The color scheme is predominantly blue and white which suggests coordinated purchasing instead of haphazard accumulation. “Rural families seemed concerned about acquiring pieces of matching color but not as concerned with sets of matching patterns – perhaps because they couldn’t afford matched sets or maybe because matched sets were not always available.”24 At least two transfer print patterns found on the shards are 22 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. Neale, Gillian, Miller’s Encyclopedia of British Transfer-Printed Pottery Patterns 1790-1930, Octopus Publishing Group, London, 2005, pages 10-17. 24 Groover, Mark, The Archaeology of North American Farmsteads, Univ. Press of Florida, 2008, page 104. 23 identifiable: “Agricultural Vase” and “Tippecanoe25.” Tippecanoe was used by John Wedge Wood of Staffordshire, England circa 1845-1860.26 Agricultural Vase was so named because it featured an urn vase in an idyllic natural or farm setting. Often the scene included livestock and other obvious agricultural overtones. The edges of the pattern may exhibit a fleur-de-lis garland. Agricultural Vase was produced by Ridway, Morley & Wear of Staffordshire circa 1840-1850.27 Seen here are intact examples of these patterns: 28 A transferware plate in the Tippecanoe pattern. 29 A transferware tea pot in the Agricultural Vase pattern. Formerly called “Singanese.” When that change took place is unclear. Available 19 June 2009: http://www.rubylane.com/shops/tomjudy/item/745 27 Available 22 June 2009: http://www.rubylane.com/shops/firesidetreasures/item/8401?hgtv=1 28 Available 23 June 2009: http://www.rubylane.com/shops/tomjudy/item/745 29 Available 20 May 2009: http://cgi.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewItem&item=250382529184&indexURL=2&photoDisplayType =2#ebayphotohosting 25 26 30 Eleven fragments of shell edged ceramics were recovered from the midden. Shell edge was a relatively simple form of ornamented tableware, typically plates or bowls, with a colored rim impressed with curved or straight lines and sealed with clear lead glaze. Shell edged, or more generically, edged wares are characterized by molded rim motifs, usually painted under the glaze in blue or green on refined earthenwares. …[They] were one of the most common decorative types used on table wares …[in] North America… [and] were the least expensive… available with color decoration between 1780 and 1860.31 Fragments of shell edge ceramics recovered from the midden exhibit a variety of styles, including neoclassical (scalloped rim edgeware with both straight and curved impressed lines) dating to the early 19th century, unscalloped with straight impressed lines dating to the mid 19th century, non-impressed (painted brush strokes) dating to the late 19th century and possibly one example of embossed which would date to the early 19th century.32 multiple examples of blue or green shell edge… with slightly different patterns could represent a “set” in which pieces could have been 30 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. Available 21 May 2009: http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/Post-Colonial Ceramics/Shell Edged Wares/Shell Edged Wares Main.htm 32 Available 21 May 2009: http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/Post-Colonial Ceramics/Shell Edged Wares/Shell Edged Wares Main.htm 31 purchased individually or a few at a time – the end result would have been a set table with everything exhibiting a very similar pattern.33 The artifacts, building/structure materials: 34 Seen here is a small selection of materials recovered from the midden which may have come from one or more buildings. These materials include bits of mortar and concrete, fired clay fragments assumed to be brick rubble and also small pieces of thickly glazed brick which may have come from a fire box or furnace lining. Fired clay fragments exhibiting flat, smooth sides resembling finished surfaces identical to those found on bricks constitute the third largest individual category in the artifact assemblage (177 items). Some of this material could have come from the razed structure indicated by the site of the subsurface brick foundation which is adjacent to the midden area. Although concrete is a 20th century product35, most of these items can not be dated in any meaningful way. They are of interest because they point to the possible existence of buildings that are no longer standing. The apparent use of brick is significant in that it indicates structures that were made for long term use, buildings that were made to outlast the builders. Scharfenberger, Gerard and Veit, Richard, “Rethinking the Mengkom-Mixing Bowl: Salvage Archaeology at the Johannes Luyster House, A Dutch-American Farm,” Northeast Historical Archaeology, vol.30/31, 2001/2002, pages 61-62. 34 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. 35 Groover, Mark, The Archaeology of North American Farmsteads, Univ. Press of Florida, 2008, page 115. 33 The artifacts, coal and coal ash: 36 Seen here are samples of coal and coal ash recovered from the midden area. Until fairly recent times, coal was a common fuel for home heating. Both houses currently standing on the farm property used coal fired furnaces. Coal ash would need to be removed regularly from a furnace and disposed of. It was probably deposited in the midden as another trash item.37 The artifacts, metal: 38 Seen here are examples of metal items (both antique and modern) recovered from the midden. Many of the older metal pieces are corroded to the point where identification and dating are difficult. Nails, bolts and nuts, wire, a fragment of chain, squeeze tube pieces and bits of 20th century tin and aluminum are among the assemblage. Most of these items appear to relate to farm work or building materials. There are only a few items linked to household refuse. A Pepsodent toothpaste tube which was recovered 36 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. Coal ash was also employed in gardens in the late 19 th century as a method of pest control. 38 Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. 37 probably dates to the period of that brand’s strongest popularity, which was before the mid 1950s.39 The artifacts, plastic tags identifying plant varieties: 40 Seen here is a selection of plastic tags identifying plant varieties. These came with newly purchased vegetables and flowers and were meant to be inserted in the soil at the end of a planted row. Thus labeled, plantings could be easily identified by type of plant and specific variety. These artifacts were not intentionally deposited as refuse but were simply abandoned after being used on site. They are among the most modern items found in the midden area and illustrate the location’s most recent function. The Fordons have used this location as a garden since the early 1980s and new plastic tags just like these are still accumulating here. Although the family remembers many of the types of fruit and vegetables grown here, these artifacts will help identify specific varieties. Preferences seemed to tend toward readily available varieties that were well adapted to local conditions. New varieties and hybrids were also frequently purchased –as opposed to heirloom varieties that were harder to find and more expensive. As seen in the photograph above tomatoes were quite popular (in part due to their versatility). Tomatoes could be made into a sauce, used as an ingredient, eaten on their own or preserved for later use. 39 40 Available 1 June 2009: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pepsodent Photographed by Michael Fordon, 2008. Conclusions: The date range for the entire artifact assemblage spans two centuries. The oldest identified item is an 1800 five cent piece and the most recent items are modern metal and plastic fragments. Most of the items seem to date to a period of about the mid 19th century to the early-mid 20th century, which coincides with the Fordon family’s occupation of the area (1837-present). The wide age range of the artifacts along with the fact that they were collected from the surface (instead of being located in the ground in datable layers) makes interpreting them problematic.41 Artifacts collected on the surface of the soil are usually a mix of materials from several time periods and often can not be assigned to particular generations since they represent a jumbled deposition. Never-theless a number of interesting facts and inferences may be drawn from the total assemblage. Assuming that the subsurface foundation adjacent to the midden was the foundation for a building (possibly a dwelling given that it was composed of brick) which was standing at the time the midden was originally in use, that would make the midden’s earliest function that of a back door trash heap for household refuse. Actually it did not necessarily have to be located at the back door. Such rubbish piles were common in the front of houses as well as the back. It wasn’t until the later 19th century that the beautification of the home and farm began to dictate that garbage was to be kept in the rear of a building to hide it from roadside or public view. A total of 1,402 artifacts were collected. Many cannot be thoroughly identified given their size, composition and lack of distinguishing characteristics. In fact the largest single group consists of 218 clear glass fragments –most of which are unidentifiable except as plain shards. However, by any estimate the majority of the artifacts seem to relate to foodways (the growing, production, preparation, presentation, consumption and storage of food). The most inclusive estimate gives a possible total of 1,025 foodways artifacts (73% of total). Although it is likely that the actual number of foodways items is somewhat lower, the estimate serves to illustrate how important this area was to the family. 41 McCann, Karen and Ewing, Robert, “Recovering information worth knowing: Developing more discriminating approaches for selecting 19th-century farmsteads and rural domestic sites,” Northeast Historical Archaeology, vol.30/31, 2001/2002, pages 17-18. Judging by the material found in the midden, the 19th century Fordons were active consumers. They purchased products made in the region (like stoneware vessels and other ceramics) as well as imported items (like Staffordshire tableware). They obviously cared something about appearances and status display given the amount of decorated tableware and color coordinated transferware they seemed to have. They liked brick as a building material and produced structures with an eye toward long term use. They ate beef, pork and fresh water clams. Tobacco was smoked on the farm but it is impossible to tell by whom (it is important to remember that non family laborers were employed and boarded on the farm and some of the artifacts could have originated with them). All of this seems to agree with the 19th century Fordons being in the upper middle class of rural land owners. The late 19th century and early 20th century artifacts illustrate increases in the Fordons’ consumption of industrially manufactured products. Just like most of the country, they began buying more factory made items that were trendy, specialized, readily available in quantity, and more efficient at performing their specific function. For example, the afore mentioned clear glass fragments included the remains of a number of wide diameter jars which were intended for food storage or preservation (canning). These artifacts illustrate the shift from earthenware/stoneware as the favored material for containers of this type to the industrially produced glass jars. Although a few of the 19th century artifacts exhibited maker’s marks, the number of manufacturer’s markings on the early 20th century artifacts was far higher. These 20th century pieces bore markings such as Pepsodent, Clorox, Pond’s, Hazel-Atlas and a wide array of partial labels, serial numbers and other markings. These findings “provide general insight into the spread of popular culture and consumerism in rural areas.”42 They also reflect “the archaeological effect of the consumer revolution …[which is that] middens often contain an incredibly large amount of discarded industrially manufactured items43 The artifacts recovered from the midden provide few specifics concerning the Fordon family. The most surprising items involve consumption of tobacco and fresh 42 43 Groover, Mark, The Archaeology of North American Farmsteads, Univ. Press of Florida, 2008, page 115. Groover, Mark, The Archaeology of North American Farmsteads, Univ. Press of Florida, 2008, page 70. water clams. The general knowledge gained by examining the artifacts largely agrees with the known history of the family. For the most part the artifacts are exactly what one would expect to find in a farmhouse rubbish pile of the period. This type of archaeology has been criticized as an expensive way to tell us something we already know. However, that criticism is more valid when applied to projects contributing directly to pubic history. In the case of small projects for the purpose of family history the amount of effort is much easier to justify. Family history is after all an endeavor in which the researcher is often personally invested. Genealogists and family historians may experience a more tangible connection with their ancestors when recovering objects owned and used by them.

![[#SWF-809] Add support for on bind and on validate](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007337359_1-f9f0d6750e6a494ec2c19e8544db36bc-300x300.png)