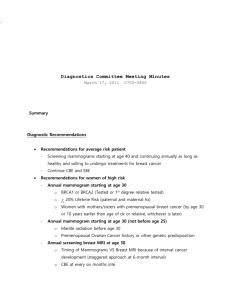

National Health Service Breast Screening Programme,(NHSBSP)

advertisement

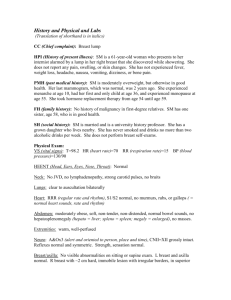

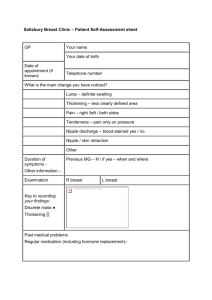

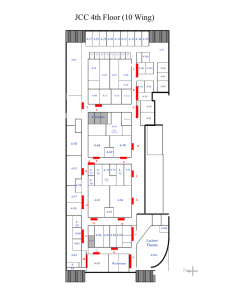

Mammography ASSIGNMENT National Health Service Breast Screening Programme, (NHSBSP) Faculty of Health and Social Care Sciences KINGSTON UNIVERSITY-ST. GEORGE’S, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Professional Practice in Mammography Post Graduate Certificate (RAM031 & RAM 032) The college of Radiographers Post Graduate Award in Mammography Practice Student No. 0853594 Word Count: 4000 CONTENTS PAGE NO. Introduction 3 Breast Screening Unit 4 1st Stage Screening 6 Assessment Clinic 7 Multi Disciplinary Team Meeting (MDM) 8 Radiotherapy 11 Conclusion 15 Annex - 1 16 Annex - 2 17 References 18 Bibliography 22 2 Introduction ‘Breast cancer is the second most common cancer overall worldwide and remains a major public health problem among women with more than 1.5 million new cases diagnosed each year’, (Hass et al., 2007), ‘Cancer screening is synonymous with secondary prevention, in which earlier therapeutic intervention is possible in an asymptomatic population to identify cancer at an earlier stage than it would have been diagnosed in the absence of screening’ (De Vita et al., 2008). As stated in NHSCSP (2010), a greater number of smaller cancers (15mm or less), which are not detectable by hand, have been found through screening. Hence, I will take this opportunity to explore the NHSBSP-UK by the experience and knowledge gained through my visits to the Breast screening unit, Assessment clinic, Multi-Disciplinary Team Meeting (MDM) and Radiotherapy department according to the Module guide (2009). 3 Breast Screening Unit Breast screening is a method of detecting breast cancer at a very early stage, (NHSBSP, 2009). The expectation is that early diagnosis and treatment lead to a reduction in mortality from the disease and /or reduction in the severity of the disease, (De Vita et al., 2008). The routine mammographic screening is an accepted standard for the early detection of breast cancer and nearly 90% of women diagnosed with breast cancer will survive their disease at least 5 years, (National Cancer Institute, NCI, 2010). Screening is distinguished from case detection which occurs when the woman presents to a General Practitioner (GP) with symptomatic disease. According to the NHSBSP (2009), in 1986, Professor Sir Patrick Forrest published a report, ‘Forrest Report’ saying that ‘In the UK, two thirds of women treated for breast cancer would eventually die from the disease’. This report further states that ‘Screening by mammography can lead to prolongation of life for women aged 50 and over’. In response to this, in 1988 NHSBSP was set up by the Department of Health providing free screening to all women aged 50-65 in the UK and this was the first breast screening programme in the world and national coverage was achieved by the by the mid 1990s,(ibid). In 2006/2007, statistics showed that for every 1000 woman aged 50-70 screened, 13.2 cancers were detected and the standardized detection ratio was 1.41, (NHSBSP, 2008). The Cancer Reform Strategy (2007), recommended the extension of breast screening to include women between 47 and 73 years old, guaranteeing that all women will be screened at least once before the age of 50, and then receives 8 further invitations. According to this, NHSBSP (2009), the programme is phasing in this extension screening women aged 47 to 73 starting in 2010 and with the intention to complete by 2012. At present, 5 breast screening units in the UK have started to implement the age extension scheme and more women can be diagnosed and treated earlier because of the changes made. This will be a big challenge for all the breast screening units in the UK because it means 400,000 more women will be screened every year, (NHSBSP, Annual review, 2009). ‘Digital Mammography, another key 4 recommendation of the cancer reform strategy (2007), is being introduced across the NHSBSP’, (op.cit). Clinical trials have found that digital mammography systems are superior for the detection of cancers in younger women and women with relatively dense breasts, (Turnbull, 2009). Furthermore, Professor Young explains the advantages of going digital which include better workflow and possibly more rapid imaging due to cassette-less operation. Storage, retrieval, copying and transmission of images should be simplified by computer storage, (ibid). In addition, breast screening units can link up with NHS’s Picture Archiving Communication Systems, (PACS). According to my experience, we can immediately see our images both on the mobile and in the department improving job satisfaction. Mammographers will get less strain on joints and hands, (Breast screening study day, 2010). I disagree with this, as they will be expected to go quicker and handle more women per day resulting in possibly more strain to their joints and hands. With digital imaging, women will benefit because of the low recall rate, (NCI, 2010) and further reducing the radiation dose, (Peart, 2005). Cassette-less operation will be quicker and should reduce women waiting times and increase the daily throughput of women. But conversely, Peart (2005) further emphasizes the loss of ability to control radiation dose to the woman and to adjust for density and contrast. The author is concerned that mammographers will lose the experience of manipulating individual technical factors working with film processing and perhaps lack of awareness of radiation protection. The author is aware that mammographers will need their IT skills improved to operate computers accurately to minimize trouble shooting with busy clinics. Thankfully, however, Quality control tests will still need to be accurately performed to enhance image quality and performance, therefore, planned well thought out training is essential for mammographers, (Breast screening study day, 2010). 5 1st Stage Screening Women are invited once in every three years for screening. Their details are obtained from the GP’s patients list. ‘Breast Screening – the facts’ leaflet in NHSBSP (2009) will be sent with the invitation letter to help the women to make an informed decision as to whether they would like to accept their screening invitation or not. This leaflet further states,’ Mammography is the most reliable way of detecting breast cancer early, but like other screening tests, it is not perfect’. There is no guarantee that screening is 100% effective and this is what women need to understand when deciding whether or not to attend, (NHSBSP, Annual review, 2009). Dr. Joan Austoker recently presented her new draft for the breast screening leaflet at a breast experts meeting on the morning of 19th January 2010, but sadly died on the same day in the evening, (The Guardian, 2010 p.41). Each year thousands of women have their first mammogram. Peart (2005), states that they come with preconceived notions about the mammogram-stories that they have heard from friends, relatives or co-workers. They seek compassion, reassurance, professionalism, education and for some even counseling, (ibid). Every step of the way, from the time they walk into the department or mobile van to the time the woman heads for home, both the mammographer and the department is under assessment. The mammography examination in fact presents a unique opportunity for us to educate our women. Women are more likely to return for a routine mammogram and comply with followup requests after a pleasant experience with a mammographer. I think, if the woman’s first experience with mammography is painful and the mammographer is unsympathetic, there is a greater chance that the woman will not return for future mammograms. Woman will also be reluctant to recommend a mammogram to their friends or family or will perpetuate the myths of mammography being a painful study, if their first experience is unpleasant. I understand through my experience, the best way to combat the misconception of mammography is good communication. We should communicate effectively with our women throughout the mammogram. This communication should not just be 6 questions and answers. We should always invite questions from the woman, then listen and encourage further comments. We are able to identify concerns and answer questions before the woman leaves. We should communicate with women clearly using eye contact so that woman can reveal any fears or misconceptions. When going through routine mammographic questioning, we should explain the procedure helping the woman to feel comfortable and relaxed. It is a good practice for women new to breast screening to explain the results procedure with the possibility of recall to reduce getting unnecessary worry if they are recalled as suggested by CancerBACKUP(2004). Assessment Clinic According to NHSBSP (2009), the mammograms are examined and results sent to the woman and her GP within 2 weeks. In 2008/2009, around 8.6% of women attending for a first screen and around 3.2% of those attending a subsequent screen were invited to the assessment clinic for further investigations because a potential abnormality was detected, (ibid). At the assessment clinic more tests are carried out at the radiologist’s request. The primary goal of the assessment clinic is to perform the triple tests, (NHSBSP Pub.49,2005) and achieve a definitive diagnosis. Lee et al. (2003), describes these tests which may include clinical examination, mammograms with different angles, paddle views, magnification views, extended CC views, ultrasound examination, fine needle aspirations, stereo-tactic core biopsies and ultra sound guided core biopsies. Hass et al. (2007) states that ultrasonography is primarily used as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of a positive finding on a screening mammography. Although ultrasonography is not the first choice procedure for most assessed women it is safe to use in young women and pregnant women who present with a breast mass,(ibid). Triple tests can be performed on the same day with the final diagnosis in 7-10 days when the woman attends the follow up appointment for results. Most importantly, the woman’s anxiety is reduced and woman can be educated about her diagnosis by the breast care nurses and have time to consider her options for care,(Alison,2007). It is the responsibility of the breast care team to coordinate follow-up and prevent any error of missed details when transferring the woman to different imaging procedures. 7 Multi Disciplinary Team Meeting (MDM) The multi disciplinary team meeting is by definition a fixed clinical commitment,(EJSO Guidelines,2009). For medical staff, this should be counted as one session or programmed activity and this reflects the time involved in preparation, the meeting itself and post-meeting administration,(ibid). In order to provide quality care, the breast care team must work together in a coordinated way such that all options are considered when discussing possible treatment strategies,(ibid). If a breast care centre utilizes the multi-disciplinary approach, it gives standard care for the woman, Siminoff(2006). Furthermore, it avoids the difficulty that woman face in organizing their care after breast cancer diagnosis, (ibid). The MDM allows the group to openly discuss treatment options and use evidence based treatment to plan optimal management of breast cancer,(Alison,2007). Those taking part in these scheduled meetings include breast surgeons, radiologists, pathologists, medical and radiation oncologists, mammographers, breast care nurses, administrative staff, trainees and a dedicated MDT co-coordinator,(EJSO Guidelines,2009). The MDT co-coordinator should have the responsibility to coordinate this process,(ibid). Furthermore, a record of attendance should be kept, and trainees should record attendance in their log book,(ibid). Although the MDM is important for teaching students, it is limited because of their busy schedule of women’s list. To be effective, it is essential that all participants are present and that the necessary data is available and prepared ahead of time. During my visits to the MDM, I understood that communication among team members is essential making sure the whole team is aware of each patient’s situation. Working as a team provides the tools to disseminate information to health care providers and to patients, which will in turn enable constant quality improvement in breast cancer care, accelerate the classic timeline of diagnosis to treatment and generate more options to care, (Malin et al., 2006). In a team members work together to explain the treatment options and their associated outcomes, as well as an explanation of why there is controversy. In this situation, womens’ values and preferences can be deliberately included in the decision- making, reducing anxiety 8 and confusion. Alison (2007), illustrates the specific objectives of multi-disciplinary breast cancer care, (Annex-1). The MDT should meet on a weekly or fortnightly basis depending on women case load. A representative from each of the ‘core members’ must be present and video or telephone conferencing if the meeting is conducted across several sites. All new patients and those with complex ongoing management issues who would benefit from a multi-disciplinary discussion should have their cases presented. The multidisciplinary meeting brings together a highly coordinated team composed of specialists from all the disciplines involved in breast cancer care. The Breast Surgeon might, for example, recommend further imaging. Ideally the surgeon can review the films with the radiologist or the images can be reviewed and reported back to the surgeon. Meanwhile, the surgeon may want to collaborate with the medical oncologist and discuss the benefits of adjuvant versus neo-adjuvant therapy as stated by Hass et al. (2007). Other specialities begin to get involved early in treatment planning, pathology, radiation oncology and psychological services, requiring other essential staff to be connected, necessary in providing quality breast cancer care. Women with a strong family history may benefit from genetic testing, (Hass et al.2007). Young women with breast cancer who are still interested in having children may need to be referred to a fertility specialist. A pregnant woman with breast cancer who does not want to terminate her pregnancy may need to be referred to an Obstetrician and Oncology specialist. Therefore, a truly integrated multi disciplinary team incorporates surgical and medical scheduling, genetic counseling, nurses and support staff into the team infrastructure to optimize care, (Alison,2007). It is also important to include the woman in all these discussions so that shared decision making is incorporated into the treatment planning. Collection of data is an extremely useful tool in many aspects of breast cancer care, (Nance et al.,2005). Data collection and documentation of recommendations should be performed for each woman, (EJSO Guidelines,2009). To enable an MDM to be successful a consensus needs to be reached among the members with recommendations based on best available evidence,(Alison,2007). The structure and 9 running of an MDM is not possible for small cancer units which may lack the specialization and resources required. By establishing a network between the local secondary centers and the larger tertiary center, whereby patients can be referred for discussion, the MDM can positively impact on cancer care for a wider group of patients. The surgeons who may be working in relative isolation have access to an MDM as a second opinion. It can be difficult to collect all necessary data on a woman when different specialities are not working together. Care for the breast cancer patient is changing rapidly and is affected by the myriad changes from clinical trials, new drug development and advances in technology,(Campos,2005). The MDM should bring specialists and scientists together providing the infrastructure that facilitates new and ongoing researches. Both NHSBSP and National Cancer Institute should encourage such research programmes and support with grants. The MDM’s principal aim should be to ensure that every woman receives optimal treatment as defined by national guidelines NHSBSP( 2009) and EJSO(2009) , an up to date knowledge of medical literature and their individual circumstances. 10 Radiotherapy I visited the radiotherapy department as a part of my clinical visits and learnt that radiotherapy was a critical and an essential part of the breast cancer treatment. 'Although radiation can be considered as a potential cause of cancer because radiation damaged DNA causing mutations, but it is because of this DNA damaging quality that it can also be used to treat cancers’,(Blows, 2005) 'The aim of radiation therapy is to deliver a precisely measured dose of irradiation to a defined tumour volume with as minimal damage as possible to surrounding healthy tissues, resulting in eradication of the tumour, a high quality of life and prolongation of survival at competitive cost’,(Halperin, Perez & Brady,2008). Souhami & Tobias(2005), describe that following treatment by surgery alone, local recurrence of disease in the chest wall, ipsilateral lymph nodes or residual breast occurs with a frequency of 7-30% and post operative radiotherapy greatly reduces the frequency of local recurrence. According to the Cancer Research Campaign(CRC) King’s/Cambridge study, the local recurrence is indeed reduced by radiotherapy (from 30-11% at 10 years) but that survival is unchanged, at least up to 10 years from initial treatment,(ibid). I met Mrs. R at the assessment clinic. Following confirmation of a breast cancer diagnosis and appropriate MDT discussion to plan management, the results should be discussed with the patient, (EJSO Guidelines,2009). According to the results of the triple tests, Mrs. R was given an appointment one week later to meet and discuss things further with a breast surgeon. Reaffirmation of information given by the Radiologist about the pros and cons of surgery options helped Mrs. R to consent for lumpectomy followed by a course of radiotherapy to avoid local recurrence. The same breast care nurse was present at this appointment. I think it is important to have appropriately trained, skilled, knowledgeable nurses available in breast clinics to give emotional support for the women. On hearing the words ‘cancer’ and ‘radiotherapy’, Mrs. R was very shocked. She was frightened that the radiation would harm her. She felt she would lose her quality of life and social existence. The 11 breast care nurse and the radiologist spent considerable time with her giving psychological and emotional support . Some women with early stage breast cancer will choose mastectomy to avoid the course of radiation, either due to the logistics of 6 weeks of radiotherapy or due to fears of radiotherapy,(Halperin, Perez & Brady,2008). An appointment was next made for her to attend the clinical oncology out-patient department with a family member or a friend in order to meet her consultant oncologist. She had notice of her appointment when she was at home post-operatively, waiting for her lumpectomy scars to heal with the knowledge that her six weeks of radiotherapy loomed ahead. Radiotherapy can engender many fears for patients. Misinformation is common, and patient’s family and friends may reinforce these concerns due to lack of information, (Yarbro, Frogge & Goodman,2005). The need for psychological and emotional support for her was equally as great as the need for physical and practical care. Her oncology appointment involved an examination, discussion of her condition, type and extent of the treatment, treatment procedure, aims of the treatment, side effects and an agreement about future plans. She understood that she was under the care of a consultant oncologist who had prescribed radiotherapy for her. It is always helpful to involve a third party- husband, partner or friend to assist the woman to recall what has been discussed. I would recommend we provide a recording of the consultation, which woman may take home and replay at their leisure to gain more understanding. It is not always enough just to tell women facts or handout a leaflet. The family members need to ensure that the message has been understood. Having three consultations with the specialist nurses and the oncologist before starting treatment, Mrs. R’s particular anxieties were discovered and as far as possible allayed. Having full information about the procedure, informed consent was given to have radiotherapy,(The statements of professional conduct, 2004). Before radiotherapy began she was given a treatment planning appointment. The first step was to determine the tumour location and its extent. Exact location is very important to determine the target volume, (Hass et al.2007). 12 For all planning techniques, quality assurance(QA) of the planning process and the daily treatment delivery is vital. This requires team work by all members of the radiotherapy department. Written directives for treatment planning, treatment delivery and quality assurance policies are still necessary. The woman’s treatment chart is used as a communication tool between staff regarding the details and flow of treatment and should be easily accessible to all members of the department. The actual treatment chart may be a computer record. Treatment planning parameters, in terms of dose and the area to be treated in the radiation field must be clearly documented in the woman’s chart. The treatment parameters may be entered into a record and verify computer system that contains all of the information about the prescription plan. The radiotherapist uses this record and verifies information during treatment delivery to ensure that all of the planned parameters will be used to treat the woman. A treatment decision was made to give external radiotherapy for Mrs. R as a series of short, daily treatments followed by a boost dose as an out- patient in the radiotherapy department. According to the Journal of Clinical Oncology(2007), an additional boost dose of radiation to the original tumour site, reduced the risk of cancer recurrence in the same breast, though it did not help them live longer,(NCI,2010). Giving radiotherapy in fewer, but larger doses may be an alternative to standard radiotherapy for some women with early stage breast cancer, according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine,(2010),(ibid). Once the treatment area had been finalized, ink markings were made on Mrs. R’s skin to pin point the exact place where the radiation to be directed. It was necessary for the patient to be alone in the treatment room, still in supine position. Although she was continuously watched on closed circuit television and could be heard on an intercom system, the fundamental sense of being cut off was hard to remove completely. Much of this natural anxiety can be reduced if the patient understands the rationale for being alone and has had an opportunity to see the department and the machines before her first treatment. Giving the treatment in fractions ensures that less damage is done to normal cells than to cancer cells, 13 (Macmillan&Cancerbackup,2008). The damage to normal cells is mainly temporary, but is the reason why radiotherapy has some side effects,(ibid). Mrs. R had some side effects of radiotherapy such as tiredness, loss of appetite, skin reactions; redness, sore and itchy. At one point Mrs. R’s skin got very sore and her treatment was delayed for a short time to allow the area to recover. She was required to have extra time to rest, try to maintain a healthy diet and drink plenty of fluids. Mrs. R was asked to stop smoking and to have nutritious food during and after radiotherapy. Research has shown that it may make the radiotherapy more effective and reduce side effects, (Macmillan&Cancerbackup, 2008). During the treatment she had regular blood count tests because radiotherapy may affect the bone marrow,(ibid). She was advised about how to look after her skin during and after the treatment. It was suggested she wear loose-fittings natural fibre clothes and not to wear a bra to avoid skin irritation if this rubbed against the treated skin,(op.cit.). Within 4 weeks after the treatment ends, any side effects experienced gradually began to wear off. There may be a slight permanent change to the texture of treated breast and occasionally swelling or thickening around the scar. Menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, sleep disturbances, vaginal dryness and emotional liability related to oestrogen suppression after breast cancer treatment can also occur. These may temporarily be responsible for a significant effect on a women’s sexual health, such as a decreased interest in sexual activity, feelings of decreased sexual attractiveness and ultimately on quality of life,(Hass et al.,2007). Although radiation therapy is associated with some side effects, it is generally well tolerated and reduces the risk of local-regional recurrence. Patient education regarding the expected side effects and long term surveillance plan are key to patient satisfaction,(op.cit.). Mrs. R had been given an appointment at the end of her treatment with her oncologist one month after finishing her course of radiotherapy to discuss her progress. A follow-up evaluation should be performed every three months for a minimum of 3 years, then every 6-12 months for the next 2 years , then annually,(Hass,2007). Follow-up recommendations are in Annex-2, (ibid). Survival 14 rates based on stage distribution following a radiation therapy were 97.9% for localized disease, 81.3% for regional disease and 26.1% in women with distinct disease,(op.cit.). National Cancer Institute(2010), states that nearly 90% of women diagnosed with breast cancer will survive their disease at least 5 years. Given these facts, it further states that lumpectomy followed by radiotherapy has replaced mastectomy as the preferred surgical approach for treating women with early stage breast cancer. Conclusion : Professor Ann Keen has mentioned that, ‘ Recent statistics show that the number of women in the UK dying from breast cancer has fallen to its lowest level in almost 40 years’.(NHSBSP-Annual review,2009). This decline in breast cancer mortality rates is proof of the real improvements in our cancer services and a tribute to the continued progress made by the NHS Breast Cancer Screening Programme,(ibid). Former Prime Minister(PM), Gordon Brown referred to the screening programme in the first of the prime ministerial debates on ITV on 15th April 2010 and David Cameron accused the PM of not increasing NHS budgets and argued that cancer outcomes have not improved under the labour government. Brown replied, ‘If people get early detection ,and that means screening, I had a woman write to me who said that she would not be alive today if we had not introduced the age extended breast screening and we had not given her the chance to see a specialist in 2 weeks’(NHSCSP,2010). Mammography often demonstrates a breast cancer before it is clinically evident, (Souhami & Tobias,2005). Therefore, I would like to thank all of the academic and non-academic staff of the Professional Practice in Mammography,2009 course for helping me to enhance my knowledge and skills to become a better mammographer to participate actively in the NHSBSP,UK. 15 Annex-1 As stated in Alison (2007), Specific objectives of multidisciplinary breast cancer care are, Integrate physicians and practitioners involved in breast care into a practice group that will re-engineer diagnostic and treatment plans to maximize quality and minimize inefficiency. Encourage and facilitate effective communication between all specialities involved with patient care. Create an organizational system and an environment to ease the passage of patients through the maze of processes and decisions at a time of emotional crisis: shared decision making, visit preparation, patient education, and patient navigation. Establish treatment plans based on presenting symptoms, stage of disease along with a set of quality outcomes (including patient satisfaction)and measures, back up by established literature, and evolving internal experience which can then be used to track quality of care. Use team approach that facilitates patient focus, constant quality improvement approach to care. Such a system will also be used to automate processes of follow-up and tracking, to reduce error and improve services. Educate to facilitate, arrange and transition to new systems of care and to make transparent the basis for treatment recommendations. 16 Annex-2 Follow-Up recommendations according to the Hass et al., (2007), The evaluation should include the following: *History and physical examination *Careful visual inspection and physical examination of the breast and regional lymphatic bearing areas. *Circumferential measurements of the mid hand, wrist, forearm, and upper arm of both upper extremities and evidence of lymph oedema. *Appropriate radiographic studies. Women treated with breast conserving therapy should have their first post-treatment mammogram approximately 6 months after completion of radiation therapy, then annually or as indicated for surveillance of abnormalities. If stability of mammographic findings is achieved, mammography can be performed yearly thereafter. All women with a prior diagnosis of breast cancer should have yearly mammographic evaluation of the contra-lateral breast. *Radiograph or laboratory studies as clinically indicated. There is insufficient data to suggest routine use of complete blood counts, automated chemistries, chest radiographs, bone scans, liver ultrasounds, CT scans and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA-15-3, or CA27.29 tumour markers for breast cancer surveillance. *Pelvic examination with appropriate Pap smear annually. If patient is in tamoxifen, ultrasonography examination or endometrial biopsy should be performed annually to evaluate for evidence of endometrial carcinoma. 17 References: Alison, M. R. (2007) Collaborative approach to Multidisciplinary Breast cancer care, THE CANCER HANDBOOK. 2nd edition, Volume 2. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Bamford, C.K. & Kankler I.H. (2003), Walter and Miller's TEXT BOOK OF RADIOTHERAPY. 6th edition. London: Churchill Livingston Blows, W.T. (2005) The biological basis of nursing: cancer. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group CancerBACUP (2005) Understanding breast cancer. 5th edition. London: British Association of cancer united patients. Cancer Reform strategy (2007) [Online] Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyA ndGuidance/dh_081006 Accessed on: 30 May 2010 De Vita V.T.et al. (2008) Cancer- Principles & Practice of Oncology, Volume one, 8th edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/ Lipincott Williams and Wilkins EJSO Guidelines, (2009) Surgical guidelines for the management of breast cancer, Association of breast surgery at BASO 2009, London: ELSEVIER, [Online] Available At: http:// www.sciencedirect.com Accessed on: 12 May 2010 Hass, M.L.et al. (2007) Radiation therapy: A Guide to Patient Care, Missouri: MOSBY ELSEVIER 18 Halperin, E.C, Perez C.A. & Brady L.W. (2008) Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. 5th edition, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Khan, F.M. (2007) Treatment planning in Radiation Oncology. 2nd edition, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Lee, L. et al (2003) Fundamentals of Mammography. 2nd edition. London: Churchill Livingstone. Macmillan&Cancerbackup (2008) External beam radiotherapy [Online] Available at: http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Cancerinformation/Cancertreatment/Treatmenttypes Accessed on: 17 March 2010 Malin, J.L.et al. (2006), How can we improve the quality of cancer care in the united states? Results of the national initiative for cancer care quality, Journal of Clinical Oncology MODULE GUIDE (2009), PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE IN MAMMOGRAPHY, POSTGRADUATE CERTIFICATE (RAM031 & RAM032), London: St. George’s National Breast Screening Training Centre Nance, M., et al. (2005) Data visualization for enhanced medical outcomes research, Annual Symposium Proceedings, AMIA, 1060 National Cancer Institute, NCI (2010) Cancer Advances in focus-Breast cancer, National Institute of Health-USA, Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/cancer-advances-infocus/breast Accessed on: 31May 2010 19 NCI (2010) Breast Cancer Screening Modalities. [Online] Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/breast/HealthProfessional/page5 Accessed on: 30 May 2010 NHSBSP (2009) Annual review, expanding our reach-The extended age pilot scheme Dr. Anthony Maxwell. [Online] Available at: http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbspannualreview2009.pdf Accessed on: 30 May 2010 NHSBSP (2008) Breast Screening - a pocket guide [Online] Available at: http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/ A-pocket-guide.html Accessed on: 5 April 2010 NHSBSP(Nov,2007) Reporting, recording and auditing B5 core biopsies with normal/benign surgery Good practice guide No. 09 [Online] Available at: http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbsp-gpg9.pdf Accessed on: 5 April 2010 NHSBSP (Jan.2005) Pathology reporting of breast cancer Publication No.58 [Online] Available at: http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbsp58.html Accessed on: 5 April 2010 NHSBSP (June, 2001) Guidelines for non-operative diagnostic procedures and reporting in breast cancer screening, Publication No.50 [Online] Available at: http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbsp50.pdf Accessed on: 5 April 2010 Peart, O. (2005) Mammography and Breast Imaging- just the facts. International edition. Singapore: Mc-Graw Hill. 20 Siminoff, L.A., et al. (2006) Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics, patient education and councelling, Washington: The National Academies Press. Souhami R. & Tobias J. (2005) Cancer and its management, 5th edition, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Statements of Professional conduct (2004), Radiography- Annex B College of Radiography: London The Guardian (2010), John Austoker Obituary -28 April 2010 Turnbull A. (2009), Expanding our reach- Going Digital NHSBSP Annual review.2009 [Online] Available at : http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbspannualreview2009.pdf Accessed on: 30 May 2010 Yarbro C.H., Frogge M.H. & Goodman M.(2005), Cancer nursing- Principles and Practice, 6th edition, London: Jones and Bartlett Publishers International 21 Bibliography : Adams, C & Jones, P. H.(2010) Therapeutic Communication for Health Professionals. Singapore : McGrawHill Kopans B. D. (2009) Breast Imaging. 3rd edition. Philadelphia : Lippincott-Ravan Baum, M., & Schipper, H.(2002) Breast Cancer : Fast Facts. 2nd edition. Oxford: Health Press Ltd. Chan,K.et.al(2001) Extent of Excision Margin width required in Breast Conserving Surgery for DCIS, Cancer (91) Clarke,B.(2007) The Fight of My Life, London : Hodder & Stoughton Coats,D. (2005) Understanding Breast Cancer. 5th edition. London : Cancerbackup Dixon, M.( 2000) ABC of Breast Diseases. 2nd edition. London : Champman & Hall Finegan,W.C.(2004) Trust me I’m a Cancer Patient. Oxford : Radcliffe Medical Press Gui,G., Houston, S.& Donovan,G.(2004) What we should all know about Breast cancer. 2nd edition. London : Mediscript Harmer,V.(2006) Breast Cancer Treatments- A Synopsis. Practice Nurse (31) Issue 8 Isaacs, R.(2006) Breast Screening for Women with Learning Disabilities, Synergy(March,2006) Johnston,S (2002) International Handbook of Breast Cancer. London : AstraZeneca Jorgenson, K. J. & Gotzsche, P.C.(2006) Are Invitations to Mammography Screening a Reasonable Basis for Informed Consent?. Ugeskrift for laeger(168), Issue 17 22 Keshtgar,M. & Stein, R.(2003) Breast Cancer . Oxford : Health Press Ltd. Keeton, S. & McAloon, L.(2002) The Supply and Fitting of a Temporary Breast Prosthesis. Nursing Standard NCBP(2005) Improving Breast Imaging Quality Standards [Online] Available at :http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11308&page=1 Accessed on : 5 July 2010 NHSBSP(2006) Breast Screening Over 70?. Sheffield : NHS Cancer Screening Programme. NHSBSP(2006) An Easy Guide to Breast Screening. Sheffield : NHS Cancer Screening Programme. NHSBSP(2002) Information and Advice for Health Professionals in Breast Screening. Pub. No. 53 , NHS Cancer Screening Programme NHSBSP, Pub. 30(2000) Quality Assurance Guidelines for Radiographers. Sheffield : NHSBSP Publishers Niclas,C. M. (2005) Guest Editorial Breast Cancer : The Chronic Disease . Journal of Rehabilitation, Research and Development (42) Issue 5. Robertshaw , K.& Coats, D.(2004) Understanding Breast Cancer London: Cancerbackup Sweetland,H.(2004) Surgical Techniques in Breast Surgery. Surgery(22), Issue 7 Valerie,F.et al(2001) Mammographic Imaging – A Practical Guide. United States: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins *** END *** 23