Oldendorp`s Contribution to the Study of Africa

advertisement

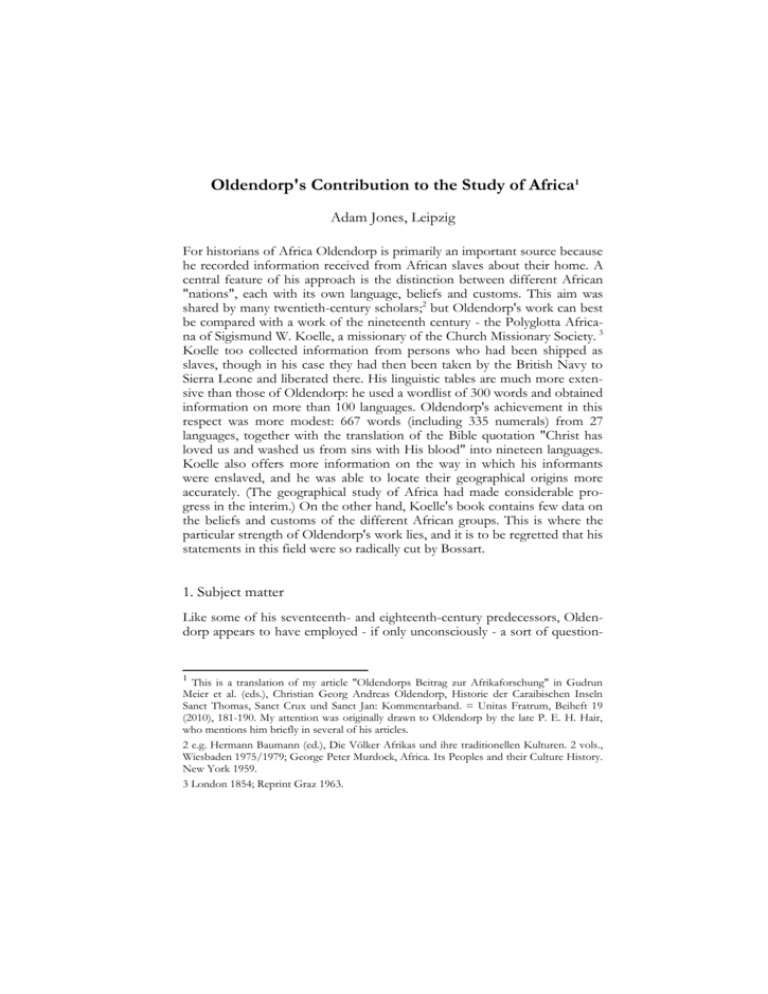

Oldendorp's Contribution to the Study of Africa1 Adam Jones, Leipzig For historians of Africa Oldendorp is primarily an important source because he recorded information received from African slaves about their home. A central feature of his approach is the distinction between different African "nations", each with its own language, beliefs and customs. This aim was shared by many twentieth-century scholars;2 but Oldendorp's work can best be compared with a work of the nineteenth century - the Polyglotta Africana of Sigismund W. Koelle, a missionary of the Church Missionary Society. 3 Koelle too collected information from persons who had been shipped as slaves, though in his case they had then been taken by the British Navy to Sierra Leone and liberated there. His linguistic tables are much more extensive than those of Oldendorp: he used a wordlist of 300 words and obtained information on more than 100 languages. Oldendorp's achievement in this respect was more modest: 667 words (including 335 numerals) from 27 languages, together with the translation of the Bible quotation "Christ has loved us and washed us from sins with His blood" into nineteen languages. Koelle also offers more information on the way in which his informants were enslaved, and he was able to locate their geographical origins more accurately. (The geographical study of Africa had made considerable progress in the interim.) On the other hand, Koelle's book contains few data on the beliefs and customs of the different African groups. This is where the particular strength of Oldendorp's work lies, and it is to be regretted that his statements in this field were so radically cut by Bossart. 1. Subject matter Like some of his seventeenth- and eighteenth-century predecessors, Oldendorp appears to have employed - if only unconsciously - a sort of question- 1 This is a translation of my article "Oldendorps Beitrag zur Afrikaforschung" in Gudrun Meier et al. (eds.), Christian Georg Andreas Oldendorp, Historie der Caraibischen Inseln Sanct Thomas, Sanct Crux und Sanct Jan: Kommentarband. = Unitas Fratrum, Beiheft 19 (2010), 181-190. My attention was originally drawn to Oldendorp by the late P. E. H. Hair, who mentions him briefly in several of his articles. 2 e.g. Hermann Baumann (ed.), Die Völker Afrikas und ihre traditionellen Kulturen. 2 vols., Wiesbaden 1975/1979; George Peter Murdock, Africa. Its Peoples and their Culture History. New York 1959. 3 London 1854; Reprint Graz 1963. 2 ADAM JONES naire when compiling information for §§ 74–79. The topics on which he questioned his informants may be summarised as follows: 1) the informants themselves 2) their scarification 3) the geography of the place where they came from, notably the neighbouring countries, whether their language could be understood and whether wars had been waged against them 4) forms of money 5) beliefs / knowledge about God, the soul, the Creation, the Flood, the Devil 6) places of worship 7) magicians, diviners and ordeals 8) justice 9) women 10) cannibalism 11) funerals 12) the slave trade and enslavement A final category (§ 80) adds further information on religious practices. Oldendorp ends Book 3 with his famous study of African languages. Additional information on Africa may be found in Book 4, especially in § 82 on the Atlantic slave trade, where Oldendorp reproduced statements by many slaves about how they were captured. Here too he leads us systematically through his list of "nations" (from Senegambia to West Central Africa) and gives us only the name and sex of the informant; i.e. the informants remain more or less anonymous. 2. The "nations" In order to make use of Oldendorp's data in studying the history of Africa, it is important to localise them as precisely as possible. The main aids for this are: Similarities between the names of the nations and recent ethnonyms etc. his linguistic material (wordlists, numerals, sentences, single words) his geographical references (neighbouring or enemy nations, rivers, distance from the sea, contact with Europeans). The languages discussed by Oldendorp are not identical with today's African languages, but can at least be classified in terms of today's language families. OLDENDORP'S CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF AFRICA 3 Appendix I combines the results of Istvan Fodor's analysis4 of the linguistic data (Columns 1-2) with a tentative attempt to find contemporary ethnolinguistic equivalents. With regard to the relative strength of the nations on the Danish islands Oldendorp writes (p. 486): After [the Creioles] the Amina are the most numerous, followed by the Karabari and Ibo, then the Sokko, Watje, Kassenti and Congo, and after these the Kanga, Papaa and Loango. The others are less numerous, there are very few Angola, and the Fula are the fewest. This statement may be compared with the number of informants named by Oldendorp when he deals with each nation in turn (Appendix II). We may conclude that the Danes, whose principal bases in Africa lay in Accra and Fredensborg (in what is now southeastern Ghana), drew most of their slaves from the Gold Coast (the Amina) and the Niger Delta (the Karabari and Ibo), whilst slaves from what are today northern Ghana, Togo and the Loango-Congo region were likewise well represented. Only a small number came from west of Elmina (in today's Ghana): a few from Senegambia, others from southern Liberia or neighbouring areas of Côte d'Ivoire. It is striking that fewer slaves came from the far interior than was the case with the persons interviewed by Koelle in Sierra Leone in the nineteenth century: 5 Only in the case of the "Mandingo", "Sokko" and "Kassenti" (as well as with some of the "Fula") is it conceivable that they had lived more than 300 km from the coast. Appendix II also makes it easy to understand why Oldendorp says considerably more about certain nations (with "good" informants), particularly the Amina (11 pages) and Watje (8 pages) than about others. 3. The ethnographic information Unfortunately it is only possible in a few cases to compare Oldendorp's statements on the tattoos of each group with twentieth-century ethnography. As he himself sometimes recognised, it was possible for a single ethnic group to have more than one form of tattoo. His information on the religion of individual groups, on the other hand, is valuable. Some of his questions were from today's perspective rather odd 4 The table is my own, but rests to a considerable extent upon István Fodor's book, Pallas und andere afrikanische Vokabularien vor dem 19. Jahrhundert. Ein Beitrag zur Forschungsgeschichte. Hamburg 1975, pp. 167f. Cf. idem, Zur Geschichte des Gã (Accran): Protten (1764) und Oldendorp (1777), in: W. Möhlig, F. Rottland and B. Heine, eds., Zur Sprachgeschichte und Ethnohistorie in Afrika. Berlin 1977, pp. 47–56. 5 Cf. Philip D. Curtin / Jan Vansina, "Sources of the nineteenth century Atlantic slave trade", Journal of African History 5 (1964), pp. 185–208. 4 ADAM JONES and probably had the effect of leading questions. It would be unwise to assume that every statement about cannibalism was meant literally. The answers to his repeated questions about the Flood can at best be viewed as an indication for the diffusion of biblical narrative motifs. Even the questions about a High God and a Devil could easily have led his informants (who in the meantime had been baptised) to present their former beliefs in a form which made them comprehensible for Europeans. 6 Nevertheless Oldendorp offers a wealth of interesting information about religion and mythology. 4. Oldendorp's sources for Africa Not all of his testimony, however, came from his interviews. Unlike some of his contemporaries (and some German politicians today), Oldendorp always tells us when he draws upon a written source, for example on page 452: "Concerning the Fida nation I have found in the written characterisations of the negro nations that they, the Papaa and the Atja have a name for God in Heaven…" Although his source references are often very concise, he seems to have made use of five printed works when writing about Africa: Allgemeine Historie der Reisen zu Wasser und Lande. Vols. III–IV. Leipzig 1749. Bosman, Willem, Nauwkeurige beschryving van de Guinese Goud-, Tand- en Slavekust. Utrecht 1704 (probably the German translation of 1709). Labat, Jean Baptiste, Voyage du Chevalier Des Marchais en Guinée, isles voisines et à Cayenne, fait en 1725, 1726 et 1727. 2 vols., Paris 1730. Römer, Ludwig Ferdinand, Tilforladelig Efterretning om Kysten Guinea. Kopenhagen 1760 (the German translation of 1769). Snelgrave, William, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade. London 1734 (the French translation of 1735). In addition we can identify three unpublished sources: He evidently used the manuscript Diarium of Christian Jakob Protten Africanus (1715-1769), whom he had known, although he does not name 6 Cf. Olabiyi Babalola Yai, "From Vodun to Mawu: monotheism and history in the Fon cultural area", in: Jean-Pierre Chrétien et al. (eds.), L'Invention religieuse en Afrique: Histoire et religion en Afrique Noire. Paris 1993, pp. 241–265; Paul Landau, "'Religion' and Christian conversion in African history: A new model", Journal of Religious History 23 (1999), pp. 8-30 OLDENDORP'S CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF AFRICA 5 him. Protten was a valuable source for "Rio Jonk" on the coast of what is today Liberia, where he had spent three and a half months in 1757. 7 For religion in Accra he seems not to have relied upon Protten, who had grown up there and later worked there by arrangement with the Moravian Brethren. Instead, on p. 422 he cites - again without naming his source - a letter sent in 1770 by the missionary Johann Schenck from the Danes' Fort Fredensborg. The tone alone ("… If one sees such a thing for the first time, one is overcome with horror…") makes it clear that the description cannot be from neither Oldendorp nor Protten. Oldendorp modified the wording of this paragraph, but retained the content. In describing Congo Oldendorp (p. 482) mentions news received from a "Missionarius", who had spoken to a son of "the King of his country" in St. Croix. I have been unable to identify this source. In his general description of religion (§80) Oldendorp makes considerable use of Protten's Diarium, i.e. both for Accra and for "Rio Jonk". Snelgrave and Römer are briefly cited, and the oral testimony of a "Kramanti black" (presumably from the Gold Coast - interestingly, this term does not occur among the "nations") is reproduced. In order to assess the importance of Oldendorp's research, it is worth comparing it with an earlier description of some of the same nations, written by another Moravian brother, Nathanael Seidel, in 1753 but never published and apparently not consulted by Oldendorp.8 Nathanael wrote of "about 60 nations" on St. Thomas and St. Croix, but named only twelve of them: Criol, Amina, Popo (Oldendorp's „Papaa“), Loango, Calabary (Oldendorp's „Karabari“), Queda (? = „Whydah“, mentioned by Oldendorp once in the form „Fida“), Congo, Mandingo (Oldendorp's „Mandinga“), Watjee (Oldendorp's „Watje“), Mandongo9 Ybo (Oldendorp's „Ibo“) and Cahsanty (Oldendorps „Kassenti“). Whereas Oldendorp wrote several pages on almost every nation, Nathanael limited himself for 2-3 sentences each. In contrast to Oldendorp's differentiated and scientific approach, his remarks on the "character" of these nations consist almost entirely of stereotypes typical of those held by slave owners: some nations (Popo, Watjee, Queda, 7 Unitätsarchiv Herrnhut, R.15.N.8.1a, Prottens Reise-Diarium 1756–1761. I hope to publish a critical editiion of this source one day. 8 Unitätsarchiv Herrnhut, R.15.B.a.No.18. „Relation von Br. Nathanaels Besuch in den Caribischen Eilanden [...] Ao. 53 [...], pp. 190–201. Seidel (1718–1782) had worked for the Moravians in Pennsylvania in the 1740s and 1750s and had visited the West Indies from there in 1753 (Beck, Brüder in allen Völkern, S. 82, 170f.). Oldendorp mentions him a number of times. 9 In the same source Nathanael writes that the Mandongo were „often captured by the Aminas“, but this may have been a mistake: according to Oldendorp, the Mandongo did not live on the Gold Coast but in West Central Africa. 6 ADAM JONES Congo) were "industrious", "intelligent", "loyal" and "one does not hear of any theft among them", but the majority were „lazy“ (Loango), cannibals (Mandingo, Calabary) or – the worst possible attribute from the point of view of a slave owner – „often commit suicide“ (Calabary, Mandongo, Cahsanty). Only in the case of the Ybo does Nathanael provide interesting information on religious customs. Thus Oldendorp certainly had predecessors, but his relatively objective tone and above all his insatiable ethnographic curiosity made it possible for him to write a work which was ahead of its time and remains extremely valuable for scholars today. OLDENDORP'S CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF AFRICA 7 Appendix I Language Family Mande Gur Kru** Kwa Benue-Kongo Bantu [unidentified] Ethnolinguistic Identification of the „Nations“ Subgroup Name given Identification* by Oldendorp Mandinga Manding, Mandinka, Malinke Jalunkan Yalunka Sokko (Nsoko) Kassenti / Kasem, Chamba Tjamba Tembu Temba [12.35], subgroup of Tem Gien Gien [33:6], subgroup of Kran Kanga Akan (Twi) Akkim Akyem Amina Akan (Guang) Akripon Akropon(g) Gã Akkran Accra (Gã) Tambi Adangbe / Adangme Ewe Atja Aja /Adja Watje Wachi / Watji Papaa Popo Wawu Ibo (Igbo) Ibo Igbo Karabari Kalabari (subgroup of Ijo) Efik Mokko Kongo group Loango Kongo Kongo Sundi Camba Kamba / Wakamba Mbete / Mandongo (Ndongo?) Kimbundu (?) Mangree Ngere [33:24] Okwa / Okwoi Wawu II10 * Names of dialects / ethnic groups / places resembling the names given by Oldendorp. In square brackets: references to George Peter Murdock, Africa. Its Peoples and their Culture History. New York 1959. ** For some linguists the Kru languages belong to the Kwa family. 10 Cf. p. 456: „He spoke of two kinds of Wawu, namely on the coast and in the interior.“ 8 ADAM JONES Appendix II Number of Informants from Individual "Nations" Page in Manuscript 392 395 398 402 403 404 415 420 421 421 425 425 431 436 440 443 451 452 456 458 463 468 471 477 478 482 the Nation Fula Mandinga Kanga Mangree Gien Amina Akkim Akripon Okwa / Okwoi Akkran Tambi Tembu / Attembu Kassenti / Tjamba Sokko / Asokko Papaa Watje Atja Fida Wawu Karabari Ibo Mokko Loango Camba Mandonga Congo Number of Male and Female Informants 1 M (in St. Croix) a few + 1 F 4M+2F 1F 1M 5M 1M 1M 1M 1M 1M 2M+1F 3M+1F 3M 1 M (in St. Croix, from Arrada) + 3 F 4M+3F 1F 1 Criole (his father was from Fida) 1F 3M+2F 4 M + 1 M in Pennsylvania 2M+1F 1M 1F 3M+1F 2M OLDENDORP'S CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF AFRICA 9 AppendixIII Neighbours and Enemies of Individual "Nations" Nation Fula Mandinga Neighbour „ Kanga Jalunkan Mandinga Fula Mangree (understand their language) Kanga Mandinga* Mangree ? Bibi (cannibals) Mangree Gien Amina Fula Enemy Remarks Sorua Bandi (King pays tribute to the King of B.) extends to the coast Amina* Fante, Akkim, Akkran, Beremang, Asseni, Kifferu, Atti, Okkau, Adansi Akkim Understands Amina language, Kommu, Assin, Fante, Agumma, Tjuvu, Wamwi, Dantjela [Denkyera], Akkran + Watje Akripon Amina Okwa / Obtains gold from Okwoi Akkim Akkran Amina, Fante Tambi / Amina Adampe Tembu Pari Amina „ „ Kassenti (proper name: Anta / Attem Page 511–12 3 9 6 Kassenti Watje Amina far from the coast 1 = day from the 404; coast, 1 = 14 days, 405, 419; 1 = 1 day from the 514 English fort; Quahu + Kanverdi = peoples belonging to A. 2 days from Danish fort 420 on the coast 421, 516 425, 426 further inland than Amina; use arrows in war; 1 lived 4 days from Accra 425f, 430, 518 431 10 ADAM JONES Tjamba) Sokko Asokko Papaa Bombra Amina / Uwang Amina, Watje Akkran, Watje Kassenti, Sokko Atja Watje (similar language) Tofa, Jani, Taku, Akisa, Fo, Dahomee, Fida Frau [= Pla = Grand Popo?], Bente [= Bante?], Nanna, Gui, gurraa, Guaflee, No Ibo (similar language), Apur, Bibi / Biwi Karabari Igan, Ero Wawu (1) Wawu (2) Karabari Ibo (1) Ibo (2) Mokko Loango Camba Mandonga Amina 6–7 weeks from the 436 coast; islamicised a) Apossu / 441-2 Apeschi [= Kpesi], Nagoo / Anagoo, Arrada [= Allada], Attolli [= Toli] + Affong belong to Papaa; b) Affong have subjugated the others; c) Allada belongs to Papaa Some are not far 443 from the Danish fort, some far; name children after weekdays, like the Amina. 451 456 456 459, 520 far from coast Bibi = an Ibo state Karabari, Bobumda Loango, Sundi * not direct neighbours Civil war: Macongo vs. Maluango Mandongo King (Areffan Congo) = in the far interior very far from coast. 3 parts: Colambo, Cando, Bongolo 464 465 469 471 477 478